Victory over Japan 1945 |

80th Anniversary of VJ Day

80th Anniversary of VJ Day

Honouring 80 Years Since VJ Day: Personal Stories of Service, Suffering, and Sacrifice

This dedicated page brings together personal and family stories to mark the 80th anniversary of VJ Day — a moment that signalled the end of the Second World War and brought relief to millions, but at great human cost.

Here, we honour not only those who served across the Far East, but also those who endured unimaginable suffering as prisoners of war and civilians under Japanese captivity. Their courage, resilience, and sacrifice live on through the memories shared by their families. As we reflect on their legacy eight decades later, these stories stand as a powerful reminder of the cost of conflict — and the importance of remembrance.

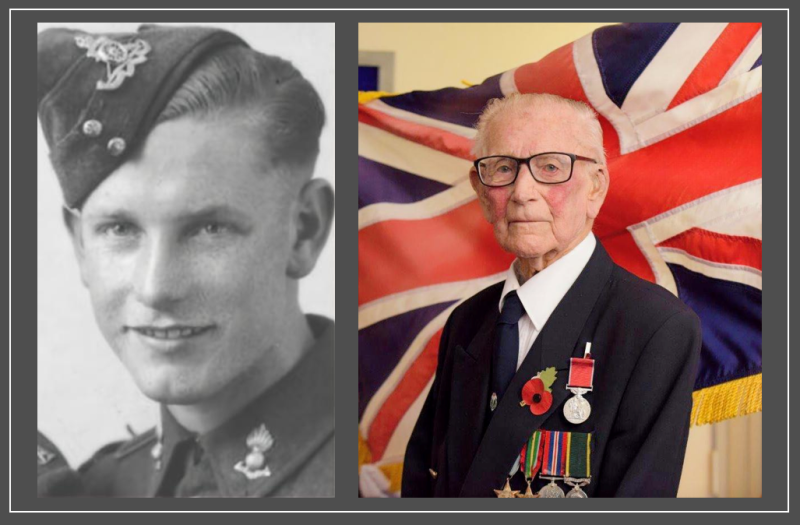

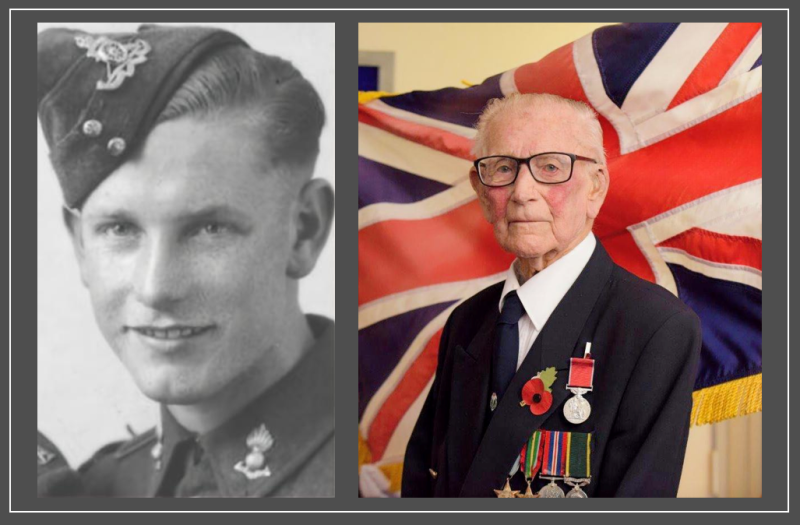

Len Gibson BEM, 125th Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery

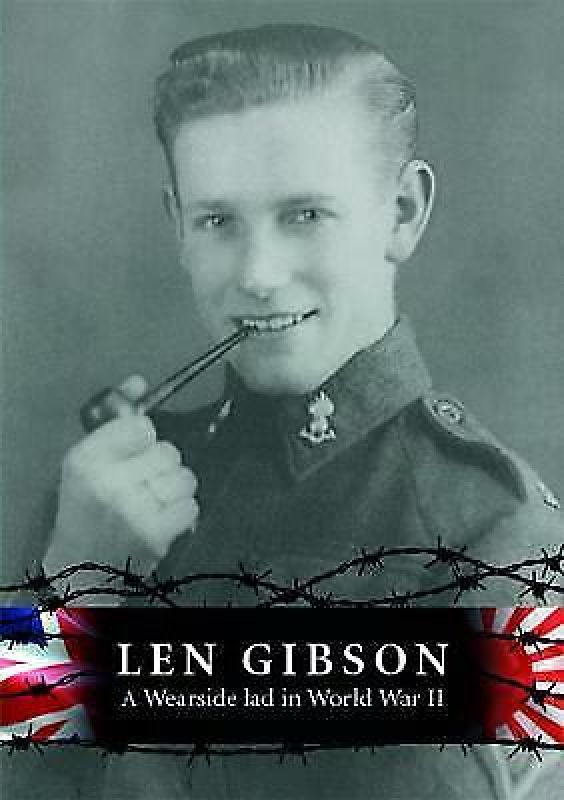

Len Gibson BEM (1920–2021) was a British soldier and survivor of Japanese captivity during WWII, enduring over three years as a prisoner and forced labour on the notorious Burma-Siam “Death Railway.”

A bombardier with the 125 Anti-Tank Regiment RA, Len was captured after the fall of Singapore in 1942. During his captivity, he suffered extreme conditions—beatings, disease, starvation, and near-death experiences, including surviving cholera and a scorpion bite. Despite these hardships, Gibson retained his spirit, even crafting makeshift instruments to play music for fellow prisoners.

After liberation in 1945, he returned to Sunderland, severely malnourished and ill. In an extract from his memoir,“A Wearside Lad in World War II’, Len describes his home-coming.

“No one could possibly describe the feelings we had when we first saw members of our families. It had been more than four years since we’d seen any of them. A tall attractive young lady ran at me and threw her arms around me. I was taken aback and as my father was shaking my hand, I looked over the young woman’s shoulder and said: “Who is this?” It was my second sister Jennie who had been a schoolgirl when I last saw her.

The drive home was along a route I had walked a thousand times. We passed all the old familiar places, places I once doubted I would ever see again. We turned into our street bedecked with flags and welcome home banners. A crowd of well-wishers were crowded around the door and it was with difficulty we managed to get into the house. And there stood my mother as I’d pictured her many times: tears in her eyes, lips quivering, speechless and ready to fling her arms around me.

That night there was a family party. Grandmother arrived tearful…Aunties arrived shedding tears. It was all very emotional, but I remained calm.

It wasn’t until a day later that my mother asked Jennie to give me her surprise. She sat down at the piano and played quite beautifully The Warsaw Concerto.

It was then that I let the tears flow. I was home with my loved ones.

My war was over.

That night I gazed at the ceiling from the comfort of my bed. I couldn’t believe my luck. How had I survived? Why had I been spared?

Every day for more than three years I had seen men die: die because of Japanese inhumanity; starved of food and denied basic medicines that would have kept them alive. Men knew death was inevitable but faced it bravely and with dignity. They were never to know that the Germans and Japanese would be defeated. They were never to know the joy of freedom. They were never to know the sweetness of success but only the bitterness of defeat. Never to know if they’d given their lives in vain.

What a tragedy! What a waste!”

After the war, Len Gibson returned to Sunderland and began a long recovery at Ryhope General Hospital, where he met Ruby, the nurse who would become his wife.

Len Gibson then retrained as a teacher, going on to teach general subjects, music, as well as serving as a deputy head. Committed to supporting fellow veterans, he helped form the Changi Club for former Far East PoWs and regularly visited the sick and elderly by bicycle.

In 2009, he was awarded the British Empire Medal.

Shortly after his death in July 2021 (aged 101!), his memoir Len Gibson, a Wearside Lad in World War II was published with the support of the charity Daft as a Brush. Obituries, recounting his amazing life and military service, were published in the Times, the Telegraph and broadcast on the Radio 4 Last Word programme.

This 80th anniversary year, to commemorate ALL FAR EAST PRISONERS OF WORLD WAR II, a statue by renowned local Sunderland artist, Ray Lonsdale, has been commissioned in remembrance. It is dedicated to those who endured years on the notorious Burma Railway and Bridge over the River Kwai, suffered near starvation, disease and brutality as a Japanese prisoner of war. Many never returned.

The statue of Len Gibson BEM will be unveiled on this VJ Day80 – Friday, 15th August at 11:00 at South Shields Town Hall.

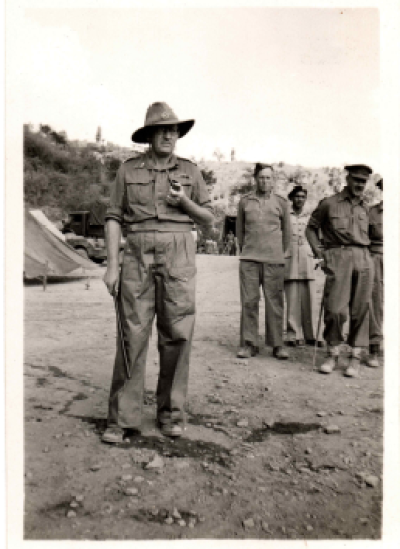

Major Leslie Washington Patterson, VX1641, 9th Division Signals, Australian Army

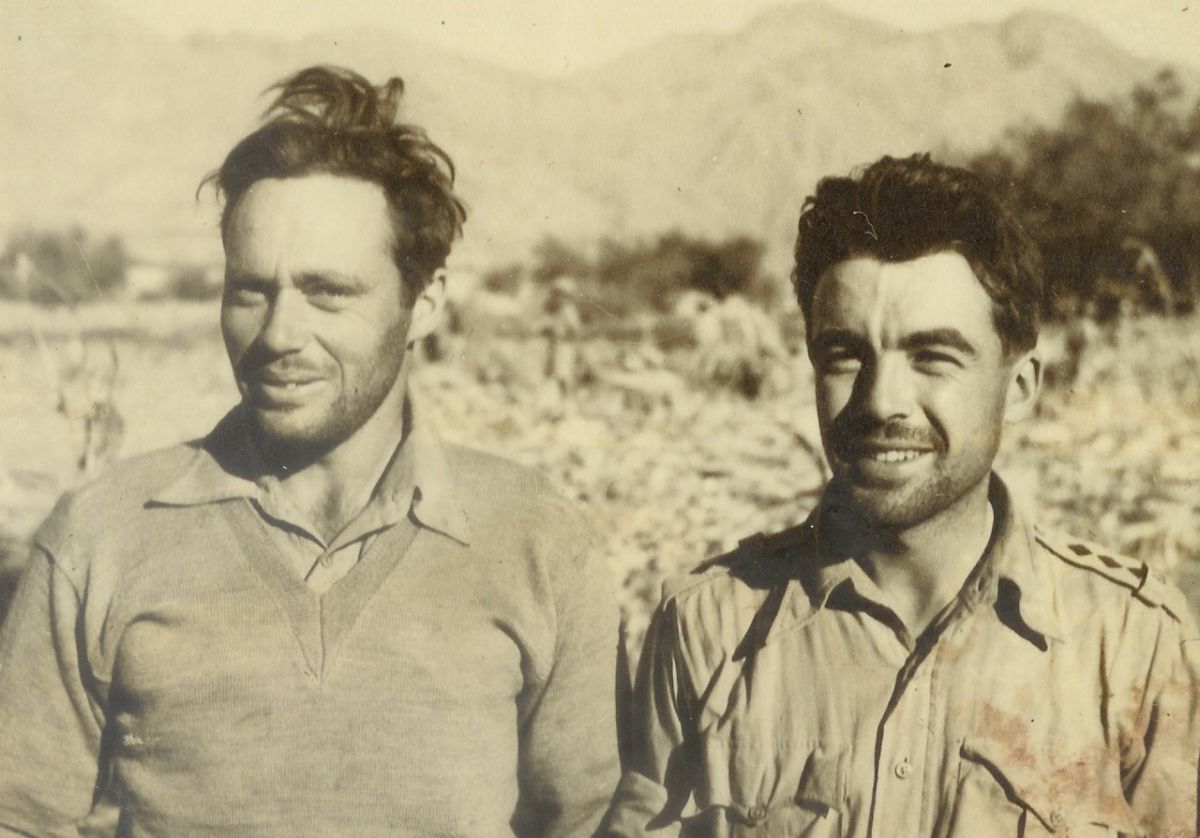

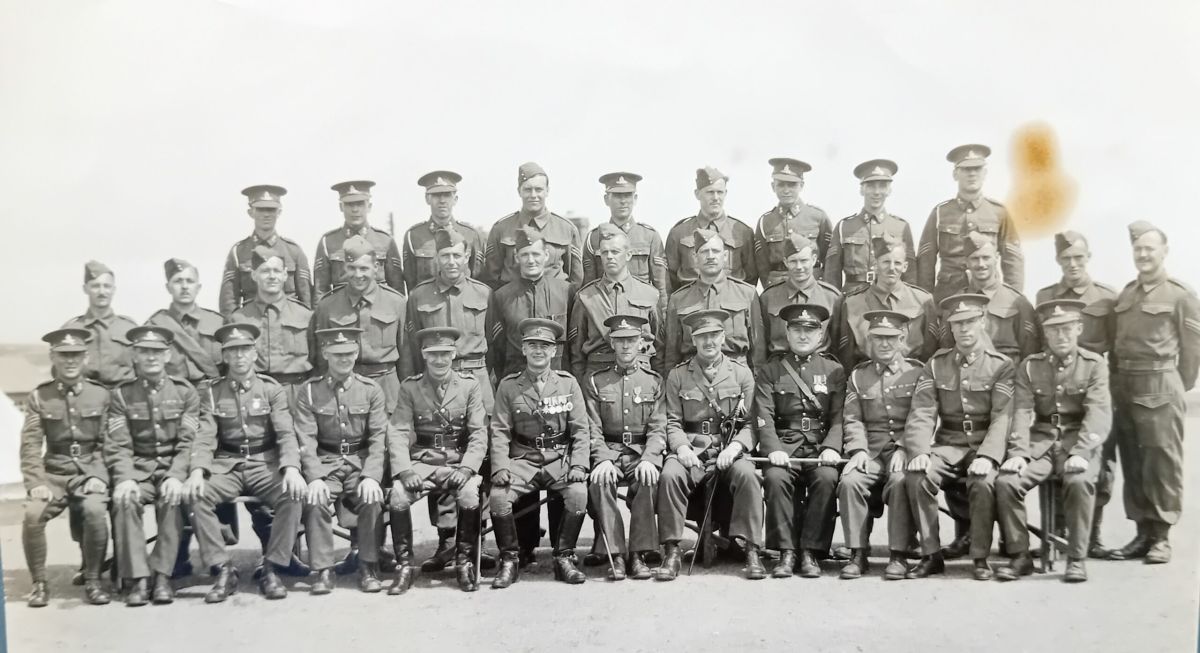

Photo above: A group portrait of Signals Officers of Headquarters 9th Division, Tobruk. The 9th Division was one of the most famous Australian divisions in WWII, known for actions at Tobruk, El Alamein, and New Guinea. Front row seated on the left: Captain (later Major) Leslie Washington Patterson, sporting a bushy mustache which, according to his grandson, he wore all his life.

Adam Michell’s grandfather, Major Leslie Patterson was seconded to the Borneo Campaign in 1945, and was stationed at Camp Pendleton on the California coast. He had the misfortune of being the Base Duty Officer on VJ Day, so at the time, in all likelihood was probably the only sober officer/soldier amongst the thousands stationed there!

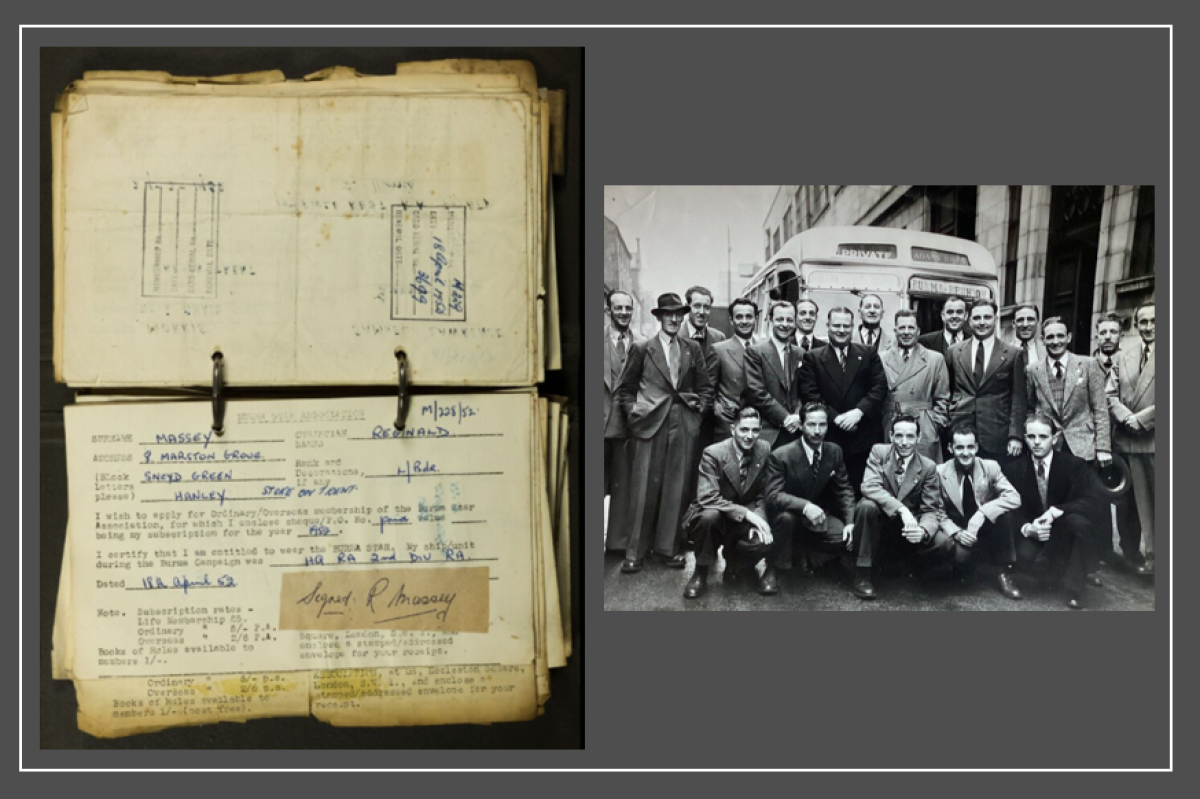

Reginald Massey, North Staffs Regiment & H Q R A 2nd Div R A, Burma Campaign

Photos above: Reginald Massey in uniform | The Burma Star awarded to Reginald is second from the left.

Vivienne Butler, daughter of Reginald Massey, recounts memories of her father, who served in Burma, for which he was awarded the Burma Star.

Reginald Massey, 1914—1973, served in India, as well as Burma in the early 1940s, before his daughter, Vivienne, was born, leaving at home his dear wife, Iris, and his three-year-old son, Barry.

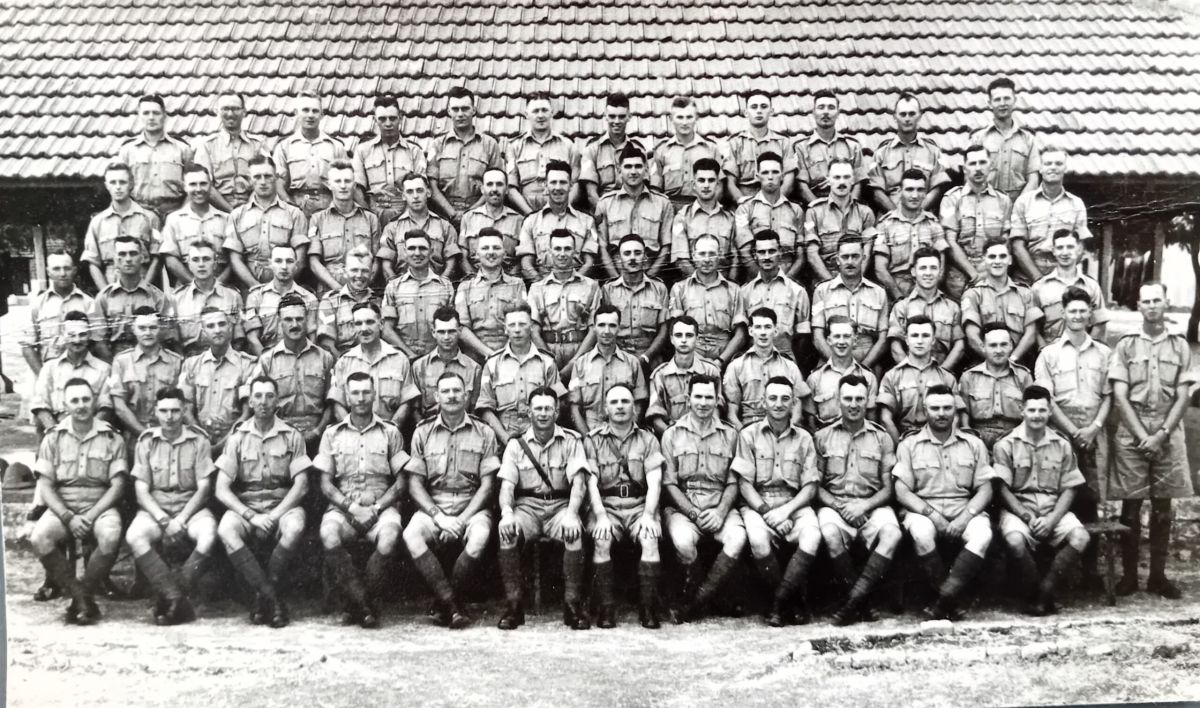

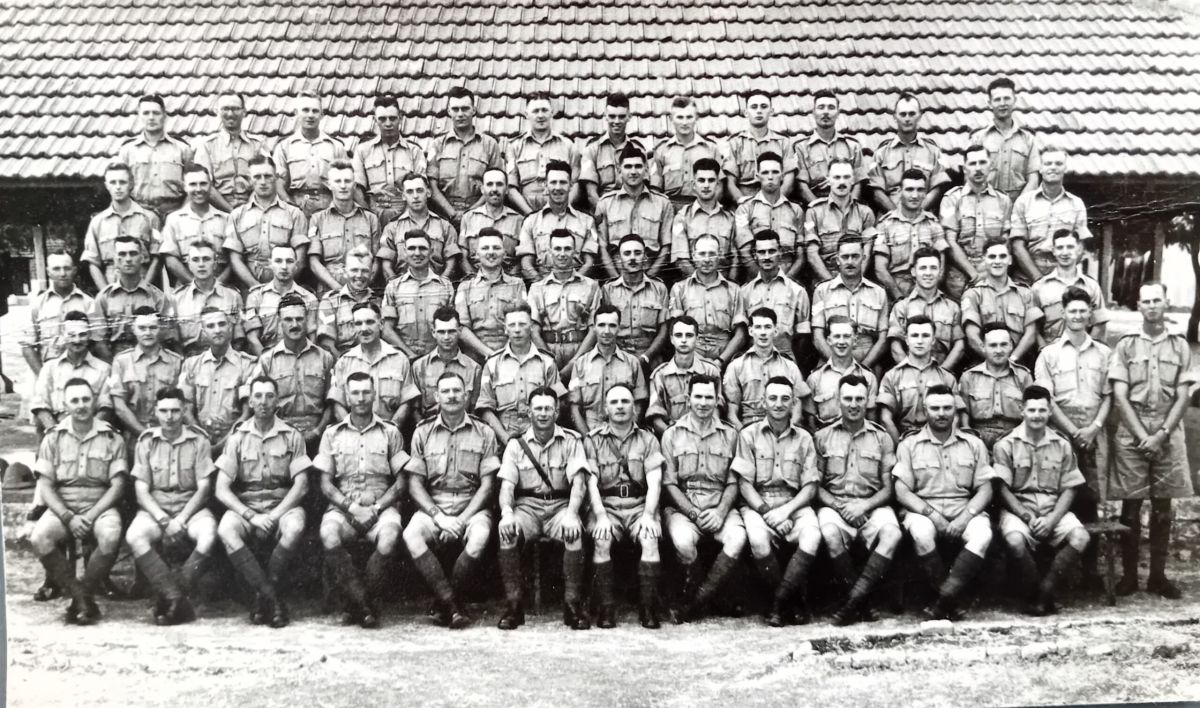

Photos above include: Reginald Massey is seated front row, second from right.

Reginald didn’t talk much about his time in the Far East, but if he did, he kept it light even though the family knew that he’d had a really difficult time during the war. He told his daughter that his job was to drive officers in a jeep from place to place. He was acutely aware that there may well be Japanese snipers en route ready to shoot to kill. Indeed, another member of Reginald’s regiment who did the same job, was shot on a journey.

He enjoyed his time in India and talked about the Taj Mahal and how magical it was. He learned a little of the local language which his daughter remembers him using during her childhood in the 50s.

Reginald’s time in Burma was a lot more traumatic which affected his physical and mental health adversely, and sadly led to his premature death aged only 59.

His daughter recalls how her mother remembered that he weighed only about 9 stones on his return from the Far East. Of course, his son, Barry, who was aged 8 by then, did not recognise him and hid behind his mother’s skirts for quite some time.

During the 50s , there used to be an annual gathering of the Burma Star Association which my father regularly attended and enjoyed. Their Saturday evening meal was always at Veeraswamys in Regent Street—the delicious Indian food reminded them of the comradeship they enjoyed in India.

Photo above: Burma Star Association members—Reginald Massey is first on the right.

Photos above include: Burma Star Association members | Reginald’s application to the Association | Group photo of Association members—Reginald is standing in the second row, third from the right.

Vivienne recalls that although her father passed away 52 years ago, his memory lives on in her heart. He was one of the best in every way.

Signalman Thomas Heckles Summerbell, 2nd Div., Royal Signals, S.E.A.C.

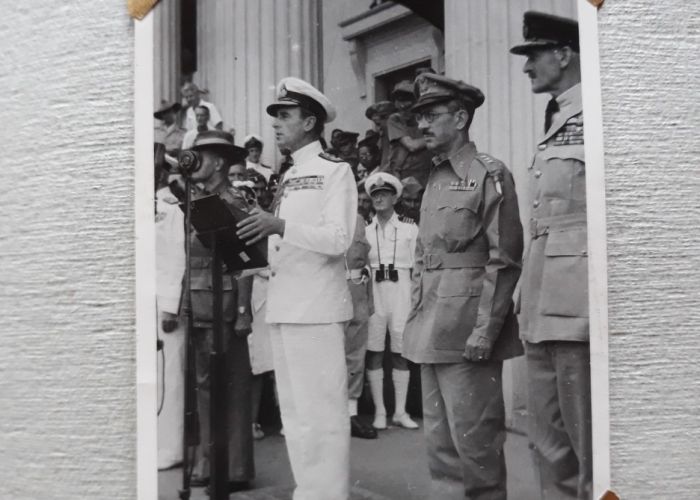

Photo Above: from Tom Summerbell’s personal collection—Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander, SEA is seen presiding over the formal ceremony of the Japanese surrender of Singapore. It was taken from the balcony in the ballroom of the Raffles hotel. The authorised press can be seen on the opposite side of the ballroom. This was sent to the VSC by Tom’s son, Fred.

What’s more, while reviewing official Ministry of Defence photographs from VJ Day, the VSC Marketing Team spotted something intriguing. In one of the images, on the balcony—fifth from the left—an onlooker is clearly seen holding a camera.

Based on the angle and perspective of Tom Summerbell’s personal photograph, this individual may very well be Tom Summerbell himself, captured in the official record of the day.

While serving in 2nd Division, Royal Signals, S.E.A.C. in Malaya and Singapore, Fred’s father (Tom Summerbell) managed, somehow, to pursue his interest in amateur photography. He never disclosed how he acquired the film, nor how it was processed, so these are likely forever to remain a mystery.

During Tom’s time serving in S.E.A.C. he had the good fortune to evade Japanese capture. Some of his friends did not share that good fortune.

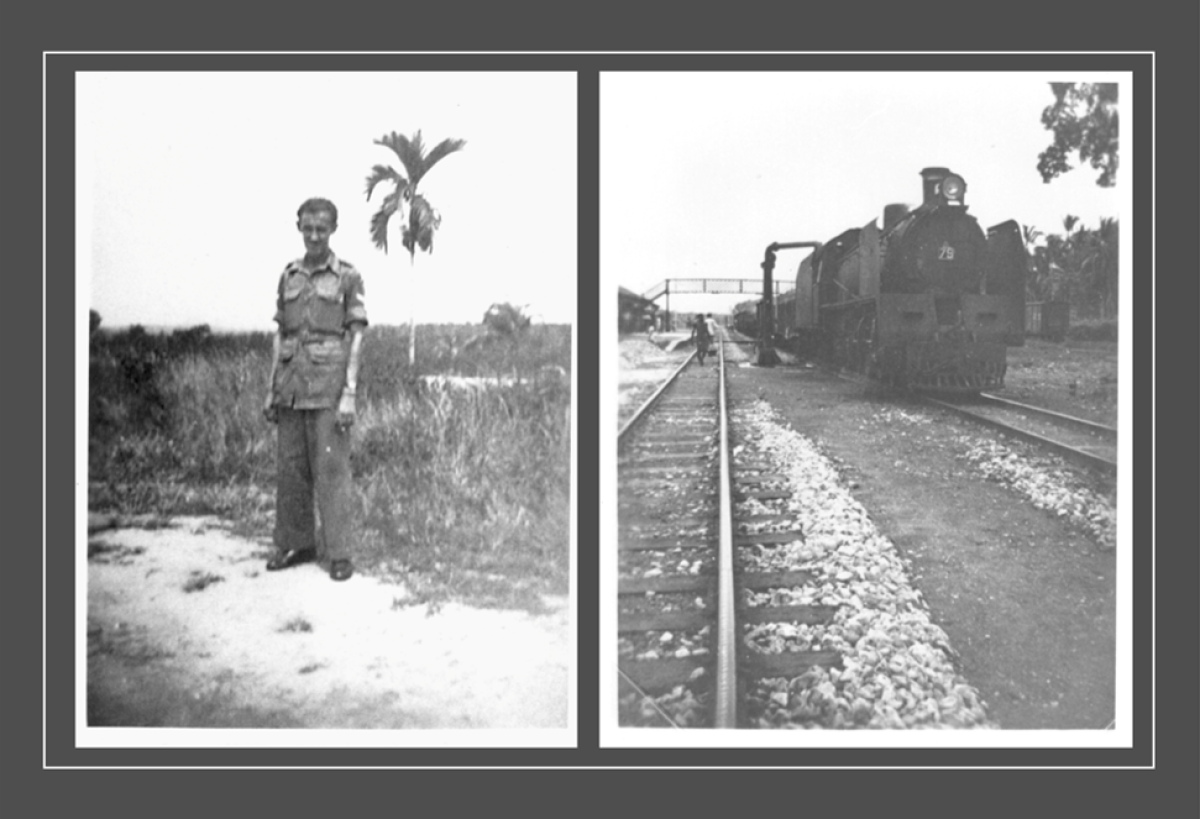

Photo Left: Sgmn. Thomas Heckles Summerbell, 2nd Division Signals, S.E.A.C, taken somewhere in Singapore, presumably by one of his pals. Photo Right: A ‘snap’ (as he refereed to this photographs) of a railway locomotive pulling a passenger train. He told his son, Fred, this was the first civilian passenger train able to leave on the Burma railway once Burma had been freed. Both he and his son, Fred (as a child), found this photograph very moving.

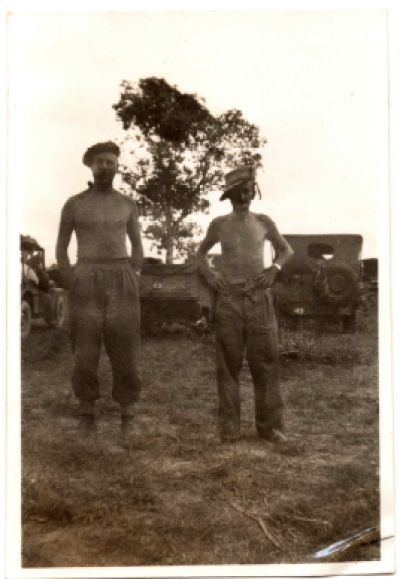

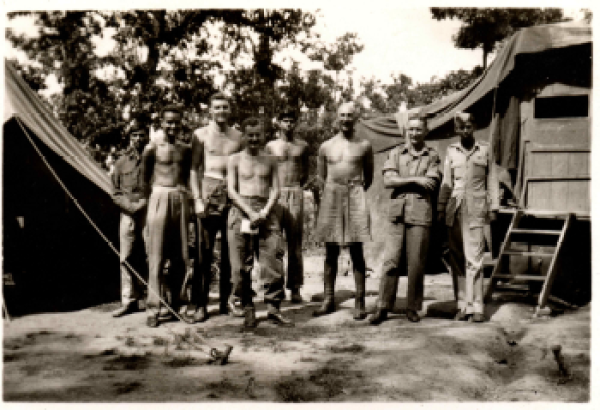

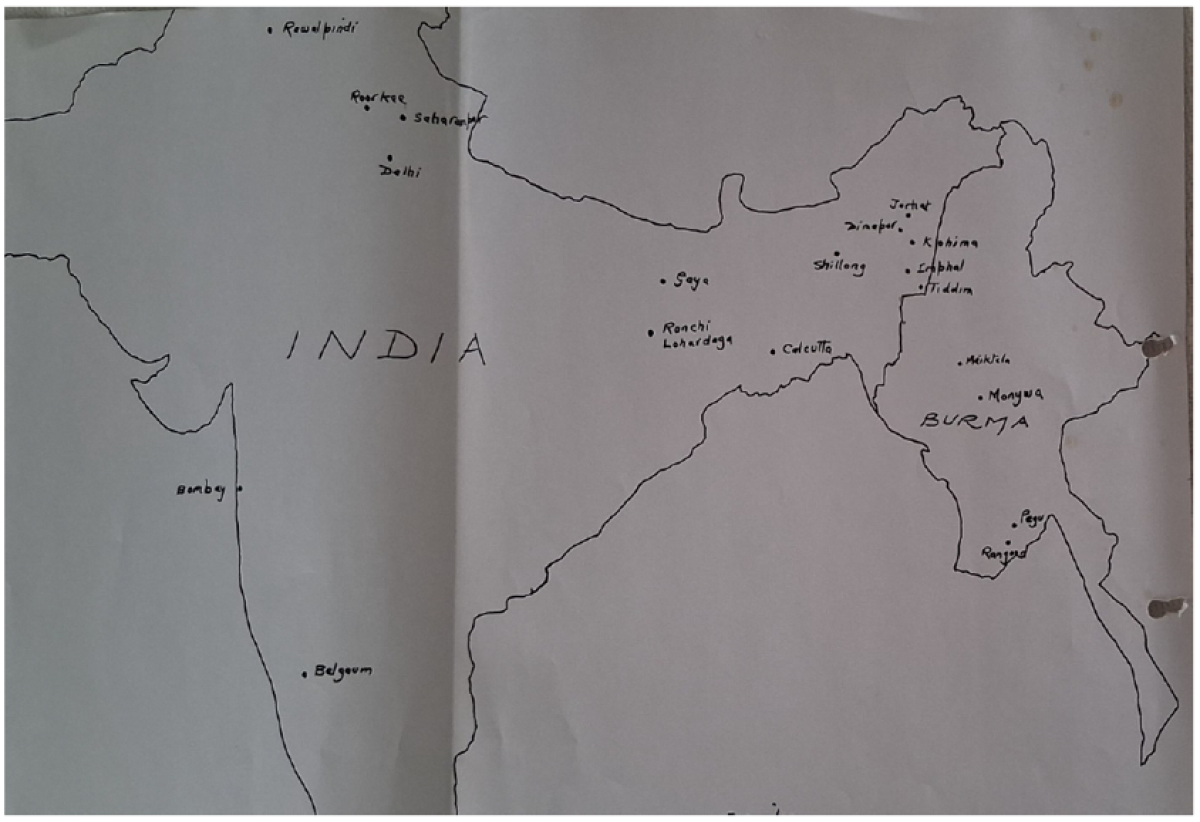

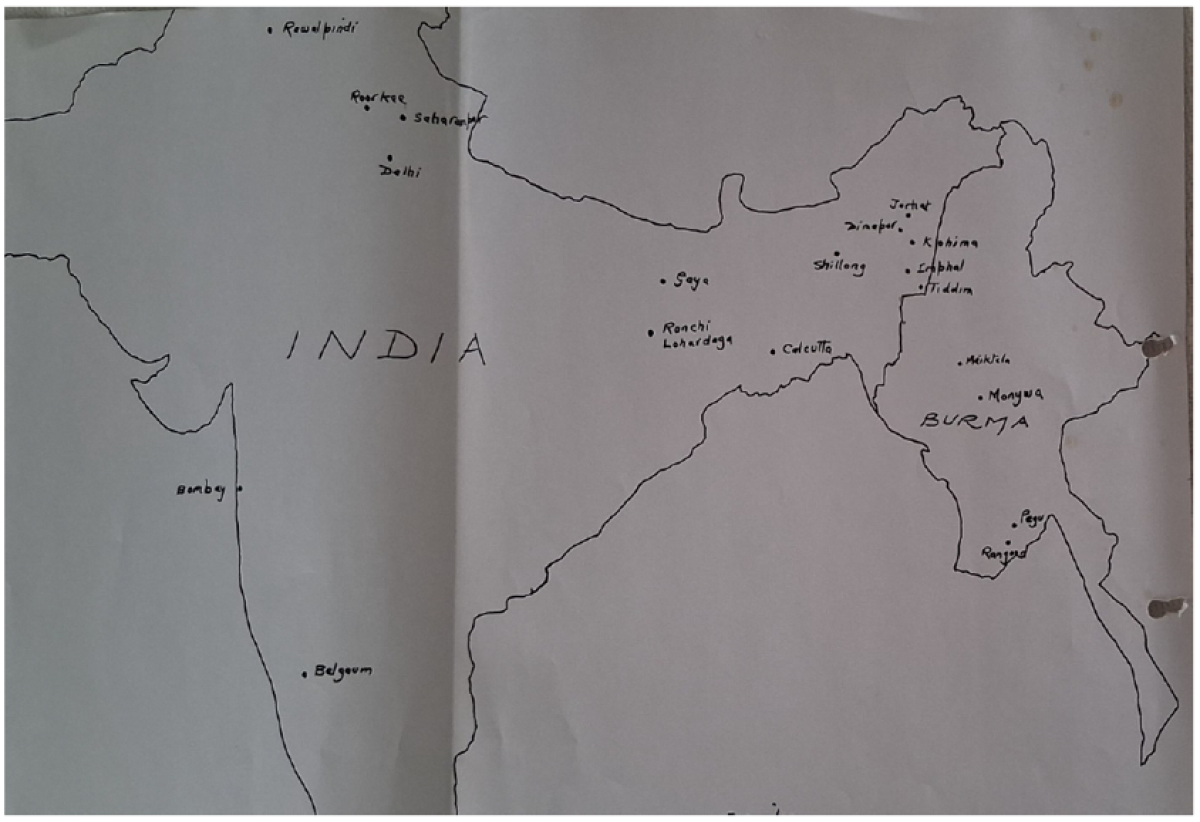

Captain J. S. White, 5th Indian Division, The Fourteenth Army

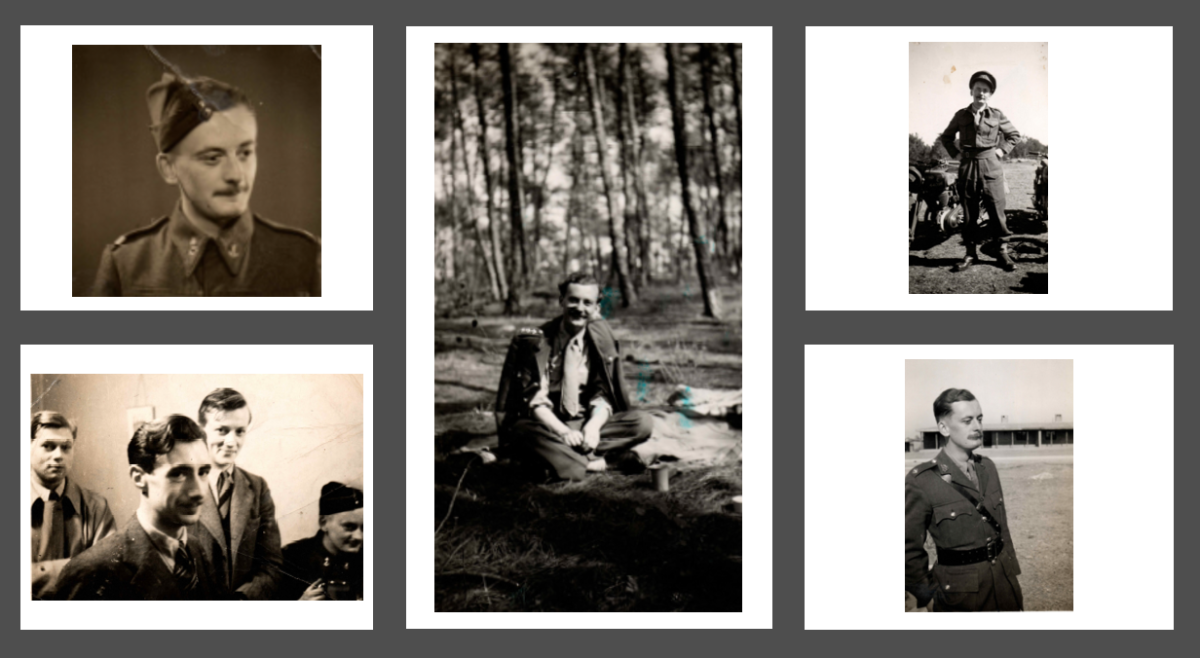

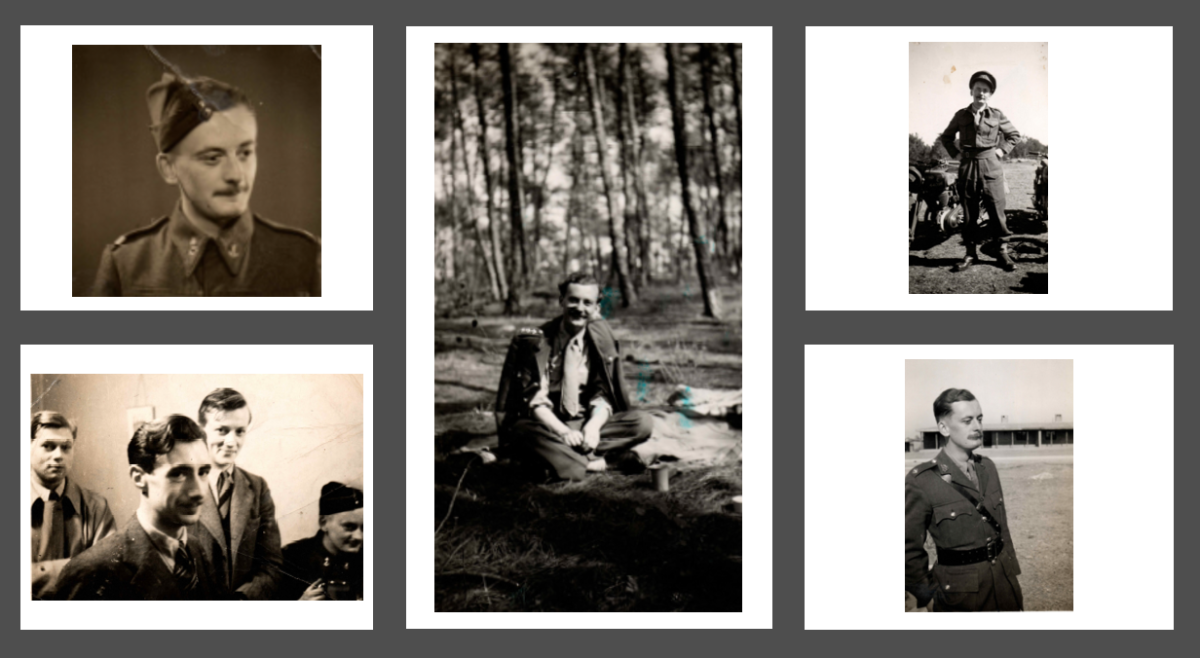

Photos above:Left: Sapper J.S.White 2194822, August 1940 | Middle: Shillong 1943 | Top Right: Shillong 1943 | Bottom Right: Rawalpindi, Christmas 1944

Captain James S White’s military career began in 1936, when, as a 17-year-old civil engineering student at Loughborough, he was recruited into the University Officer Training Corps. Trained in the inspection and repair of field guns, vehicles, and optical equipment, he was commissioned and posted to India in 1941.

-

1942 Transferring stores | Rail to Ferry en route to Shillong -

HQ I.E.M.E. 5th Indian Division -

HQ I.E.M.E. 5th Indian Division -

Imphal 1944

Following a variety of postings from Shillong to Rawalpindi to Imphal and serving with the I.E.M.E. 5th Indian Division, Captain White was eventually posted to Central Burma, as part of the Fourteenth Army. This was a large and diverse Commonwealth force that fought in the Burma Campaign. It primarily comprised British, Indian, and African troops, and was known for its resilience and eventual success in pushing back the Japanese forces.

As they advanced through Burma, the pace of movement increased, often covering 20 to 30 miles per day. Japanese resistance intensified, with frequent low-level air attacks on their headquarters. At night, retreating enemy troops attempted to infiltrate Allied lines—quietly observed by Captain White and his men.

The advance finally halted at Waw, just north of the city. It was here that Captain White received news of his repatriation-after nearly four years abroad!

On the voyage home, soldiers were warned that their efforts might go unrecognised—echoing Lord Mountbatten’s remark after the Siege of Imphal: “You call yourself the Forgotten Army, but as nobody at Home has ever heard of you, you cannot be forgotten.”

Recognition finally came decades later. Fifty years after the war, Captain White marched with thousands of veterans in the long-overdue Victory Parade for the Fourteenth Army. The cheers and cries of “Well done” from the crowds lining The Mall were, at last, a fitting tribute.

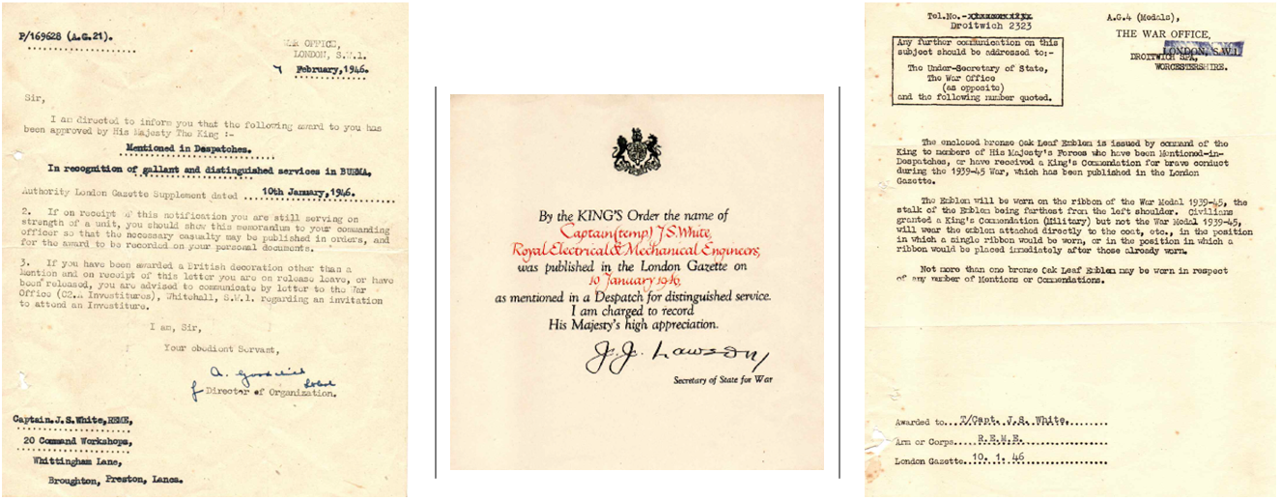

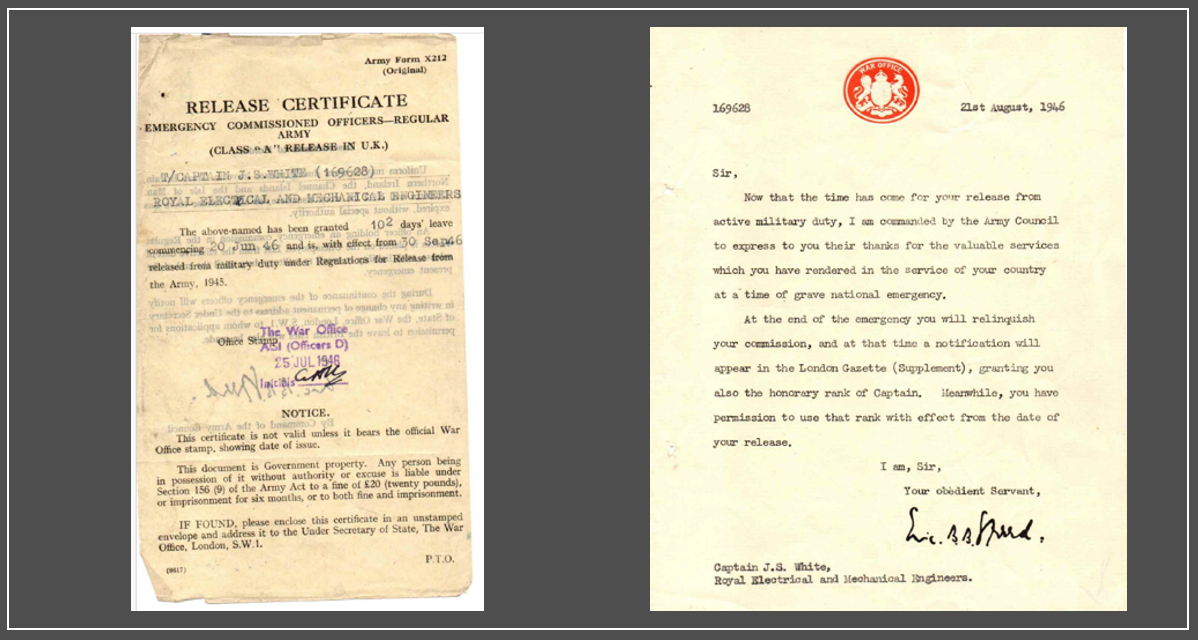

Captain J.S. White – Service Documents

Captain J.S. White – Mention in Despatches

Captain J.S. White – Release Papers

Sergeant Bill Readman, 2nd Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment

My grandfather, Bill Readman, was a Burnley lad who joined the East Lancashire Regiment in 1936 at the age of 21. He was initially posted to the 1st Battalion and spent some time in Northern Ireland. A year later, he transferred to the 2nd Battalion, where he would serve for the remainder of his military career. His service took him far and wide—first to Ambala in India, then back to the UK for south coast protection duties in Sussex, followed by deployments to the Middle East, Madagascar, and eventually Burma.

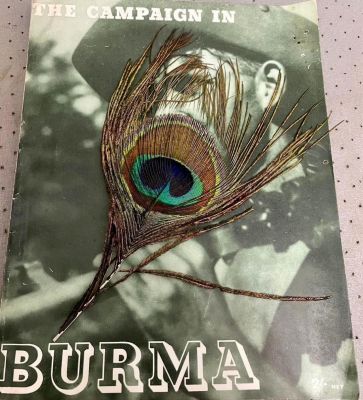

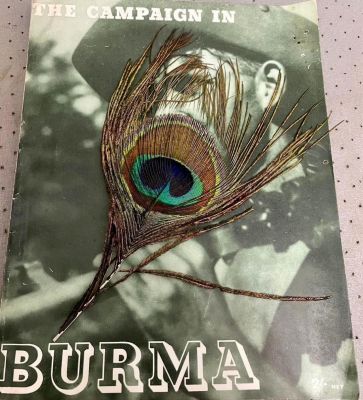

From the few mementos that have survived, I’ve been lucky to inherit some remarkable keepsakes. One is an airmail letter he sent to his sister, which included a bundle of Japanese-issued rupees as a Christmas gift. Another is a single peacock feather he plucked from a dead bird while entering a Burmese village that had just been vacated by Japanese forces.

There were also family stories—like the one about him collecting diamonds, rubies, and sapphires while filling his water bottle from riverbeds. These he apparently sent home to his sister, though they sadly went missing over the years. And then there’s the more mysterious tale of the ‘Big Lady’ at the Shillong rest and convalescence camp in Assam, who, as the story goes, had a magical ability to ease all his jungle aches and pains.

Tragically, my grandfather passed away in 1964 after a short illness. My mum always believed it stemmed from a head injury—a ricocheted Japanese bullet to the forehead—that eventually led to a slow-growing tumour. I was born in the 1970s, and sadly, I never got to meet him.

Uncovering my Grandfather’s Story: The Challenges of Military Research

I grew up hearing stories about my grandad from my mum. Being a bit “army barmy” myself, I was particularly drawn to his military service—especially his time in Burma. Like many veterans, he rarely spoke about his experiences, and as a bit of a “Quiet Man,” he kept most of it to himself. I knew very little about his movements or what he went through.

My research journey truly began in the 1990s. I had just been posted to my Commando Troop and was preparing for my first taste of the jungle in Brunei. That experience sparked a deeper interest in uncovering my grandfather’s story.

Like many others, I wrote off to the Army Records Office. I waited what felt like forever, received a couple of rejections, and eventually had to send in a reissued death certificate and a permission letter from my mum. Finally, I got my grandad’s service records.

I remember feeling a little underwhelmed at first. The documents didn’t reveal much—just names, dates, and what seemed to be a reference to a “motor course” (which, amusingly, turned out to be a typo. It should have said “mortar course”).

Still, there were interesting details. His rank progression looked like a yo-yo—rising and falling in quick succession. Not satisfied with what I had, I posted an ad on Ceefax’s “Service Pals” page, hoping someone who knew him might see it.

Amazingly, a few weeks later, I got a response from Arthur Taylor, who had served in the 3-inch Mortar Platoon alongside my grandfather. That message opened the door to another connection—Charles, another of my grandad’s wartime mates. The information they shared was priceless.

What meant the most to me was hearing the personal stories—how well-liked my grandad was, how fair he was with the men, and how much fun he brought to life off-duty. It made sense why his rank kept jumping between Lance Corporal and Sergeant—he was clearly a character!

Unfortunately, things went quiet after that. I had to deploy, and in the time that passed, both Charles and Arthur may have sadly passed away. I often wish I had followed up more, but I’ll always be grateful for what they gave me.

Over the years, my research has come in fits and starts. I contacted the Lancashire Regimental Museum at Fulwood (still on my list to visit) and received a nominal roll from the adjutant—useful, but not a major breakthrough.

I also obtained a regimental diary and history, which turned out to be a great resource. For anyone looking to track their relative’s unit movements or operations, I highly recommend this approach. In that diary, I found a photo of my grandad with other Sergeants and Warrant Officers in Mongmit, February 1945.

Despite combing through hundreds of photos and books, the chances of finding another image of him were slim. After all, over 300,000 British troops served in Burma during the campaign. But then I turned to the Imperial War Museum (IWM) archive. I focused on pictures connected to the East Lancashire Regiment and tracked down the army photographer who had documented their movements—Sergeant Stubbs.

Through that search, I found two more photos of my grandfather. One shows him spotting mortar rounds while on comms for his team—a dynamic shot. The second is of him on jungle patrol or recce. I was unsure at first, as the IWM listed it as a Welsh Fusiliers patrol. But my mum insisted it was him. Then, thanks to an excellent military forum, I learned the patrol was led by Captain E.C.H. Dewhurst, a Fusilier officer and the Senior Mortar Officer. Confirmation at last—what a moment! (Special thanks to the late Ted Jones MM.)

Photo: Bill Readman spotting mortar rounds while on comms for his team.

Photo: Bill Readman is the third man back in the patrol.

And so, my research continues. The small wins keep coming. For those hitting dead ends—don’t give up. I’ve had plenty, but each time I’ve found a new way around the obstacle. I truly believe that with enough digging, you’ll uncover something meaningful.

Looking ahead, I may be posted to India next year with my government work. If so, I’m planning a trip to Shillong to visit the ‘Big Lady’.

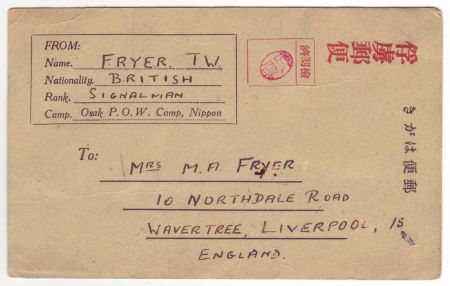

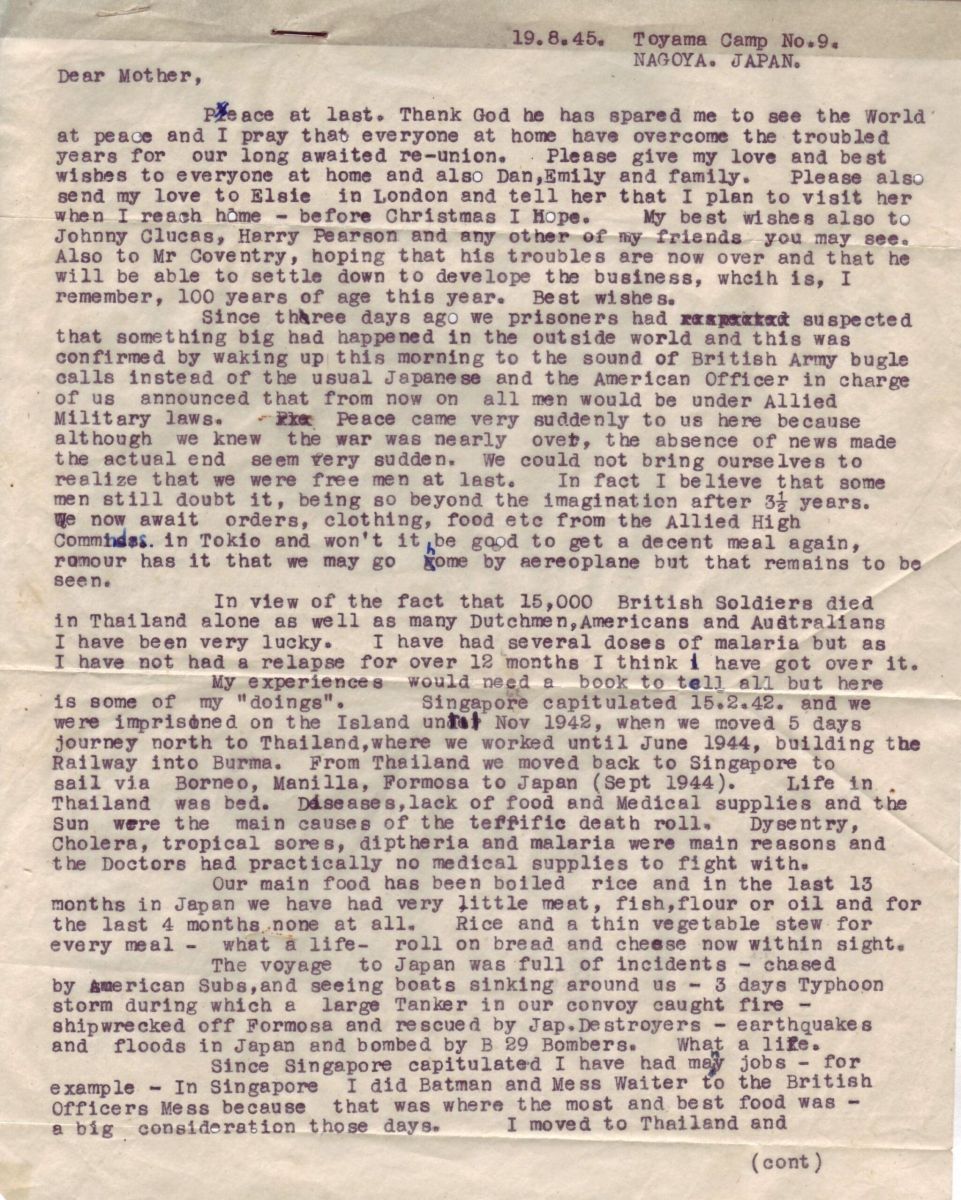

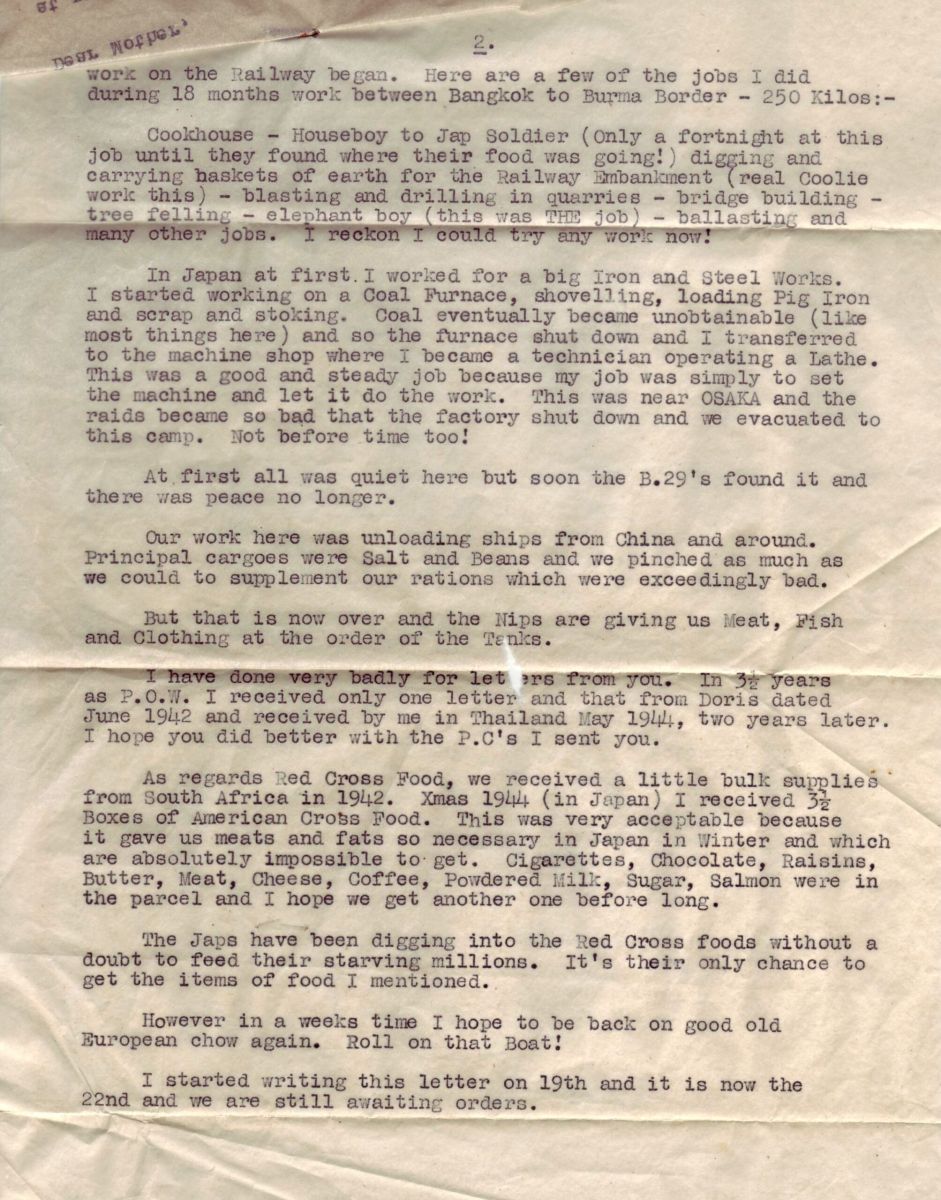

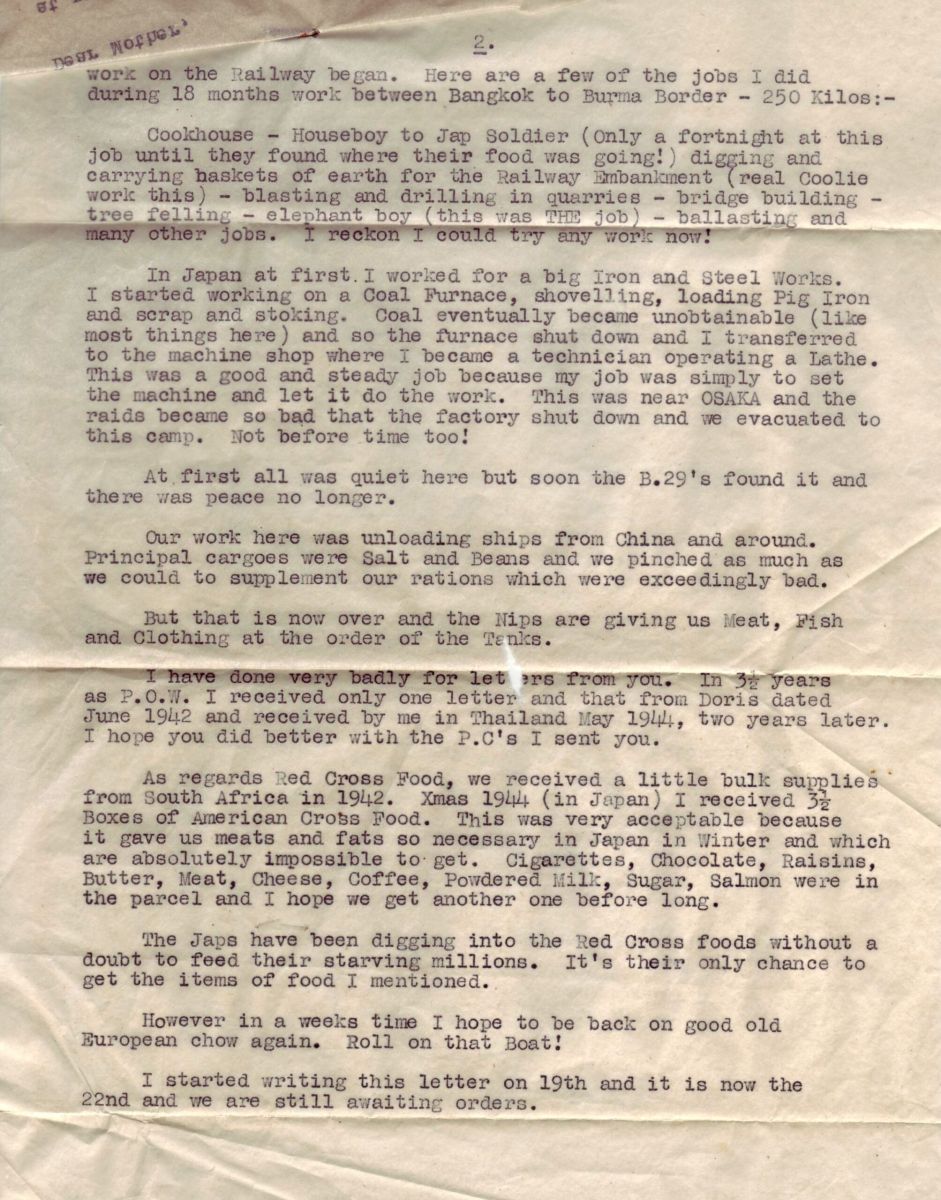

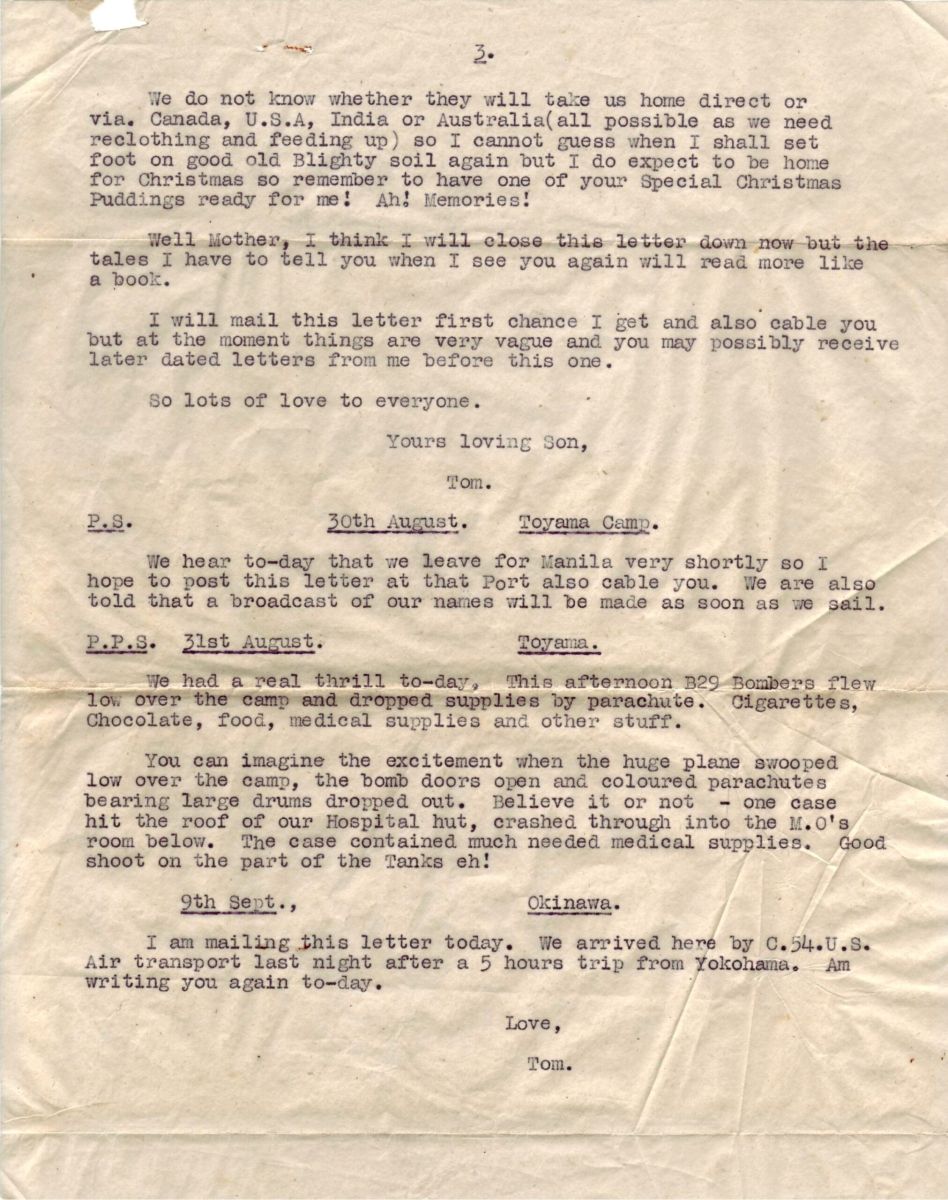

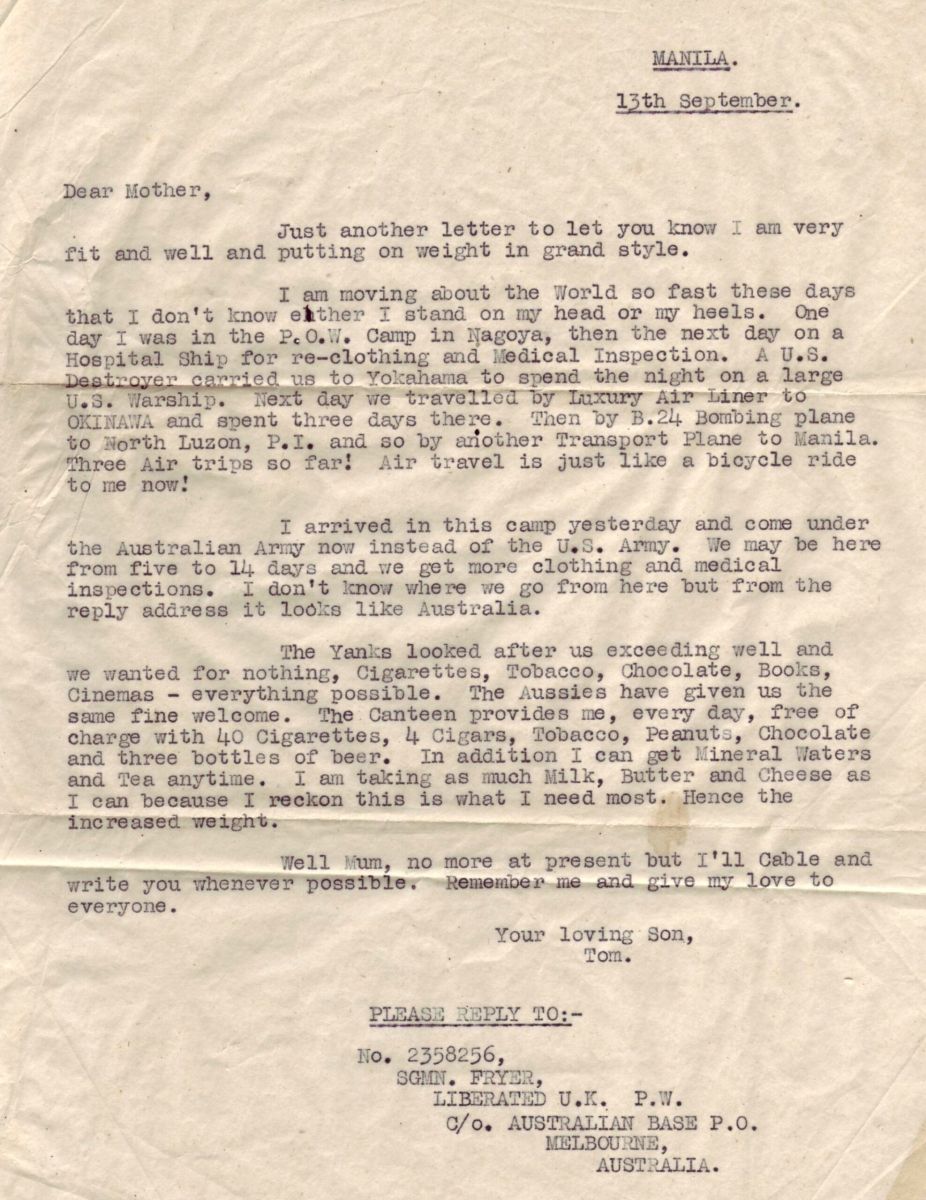

Signalman Thomas Walter Fryer, POW, Kwai Railway & Japan

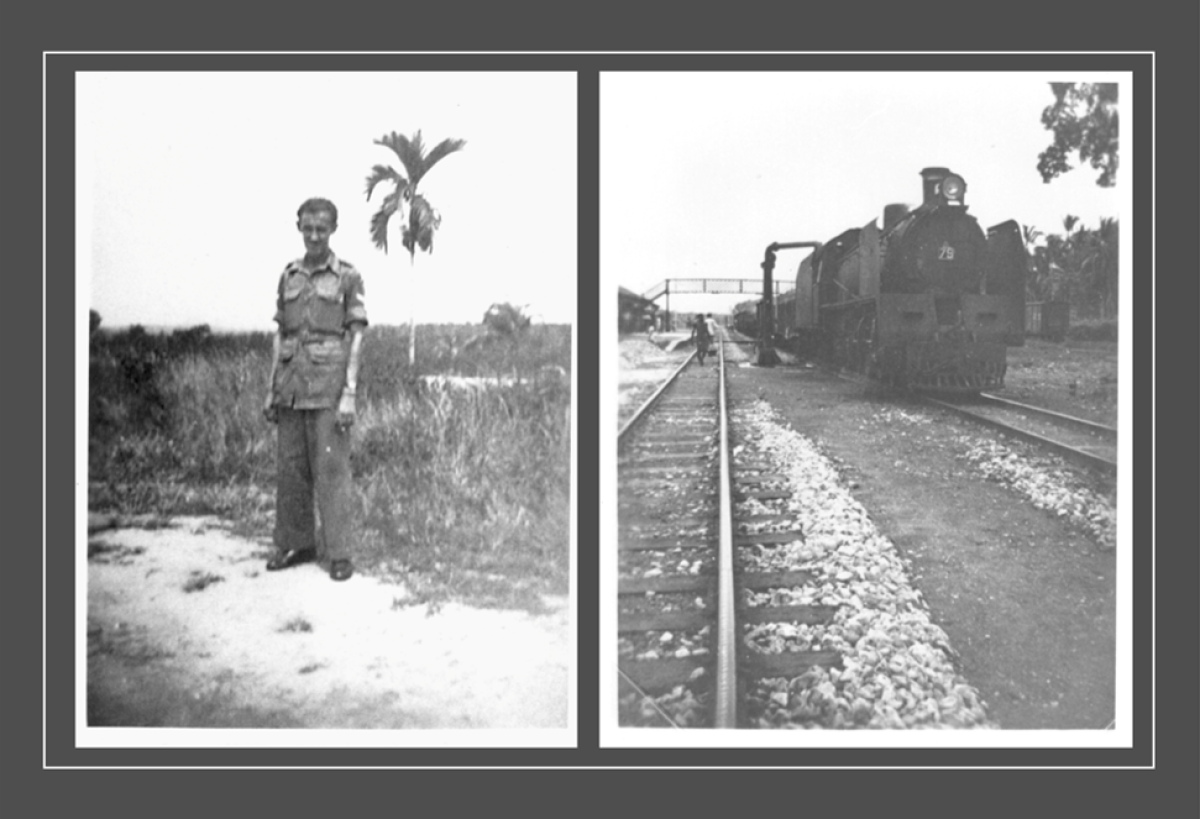

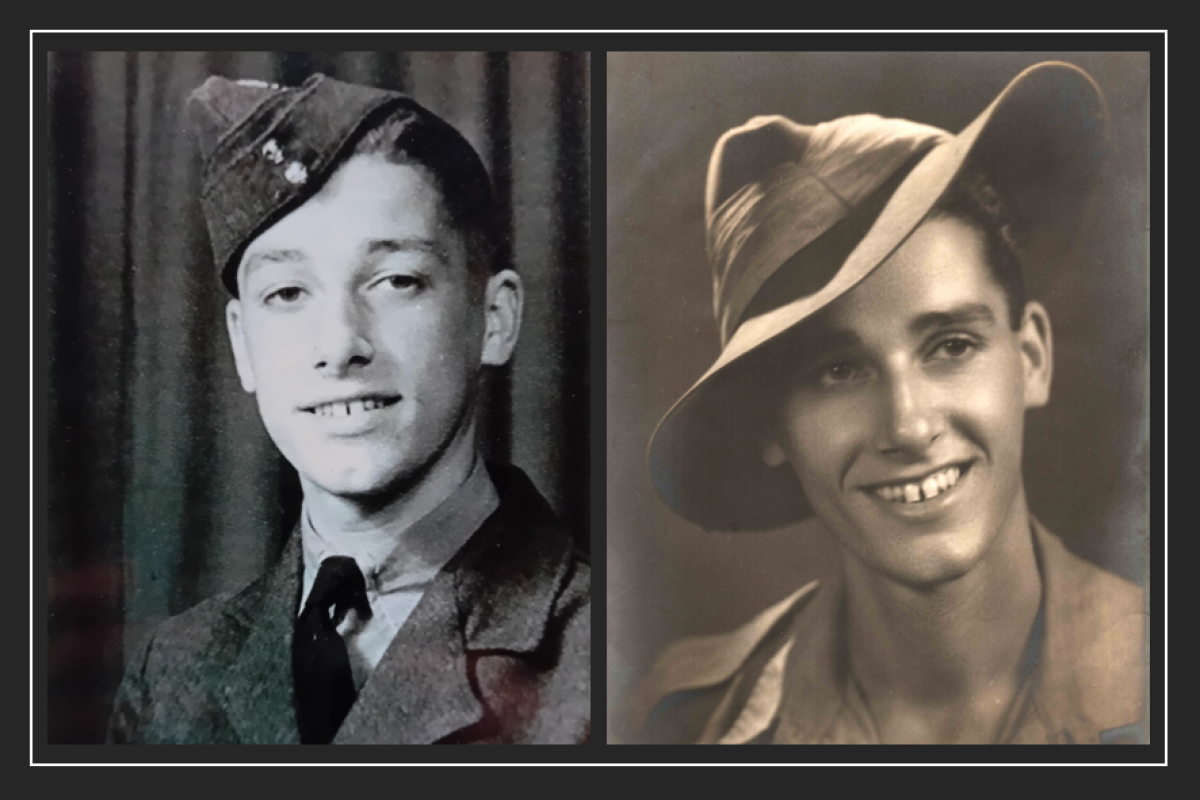

Photos Above: Signalman Thomas Walter Fryer, probably taken in the early days of WWII

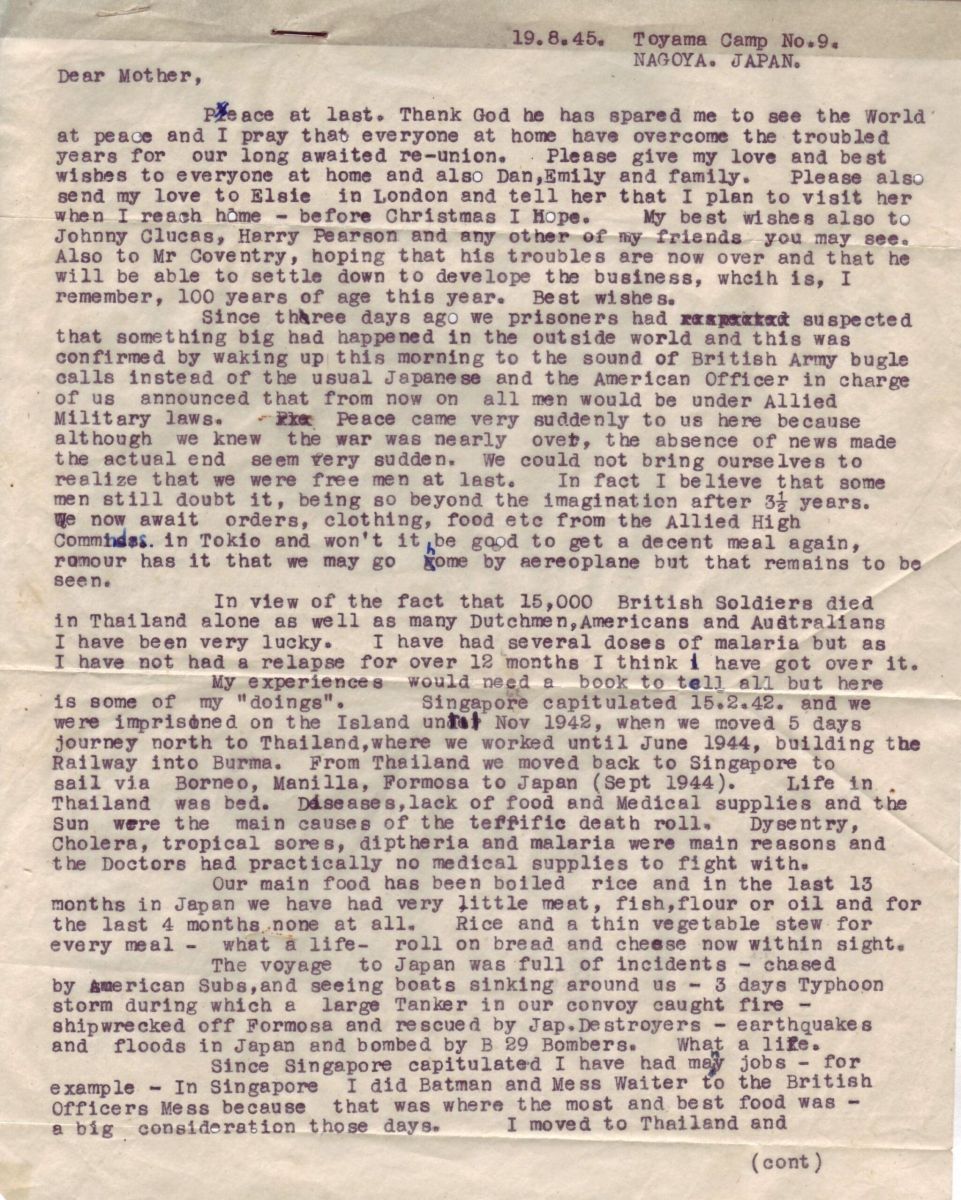

Thomas Walter Fryer (1915-1990), father of Alan Fryer, was at the fall of Singapore. He was a POW on the Kwai railway and later in Japan. After his wife, Alan’s mother, died in 2016, the documents below, which belonged to Alan’s father were found among her papers.

In a personal, first-hand account drawn from a talk he gave, Thomas Fryer describes what life was like as a POW. Click here to read more: Life as a POW.

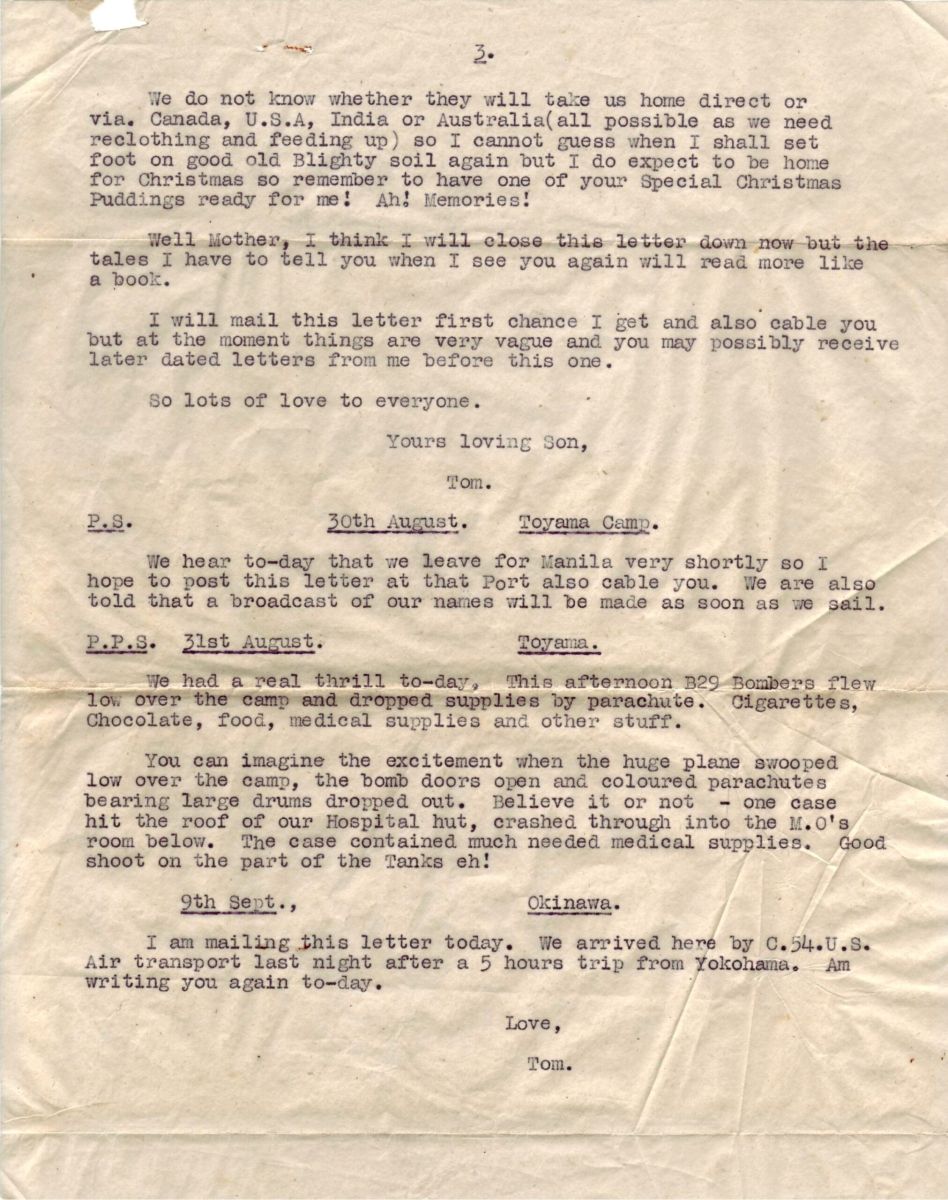

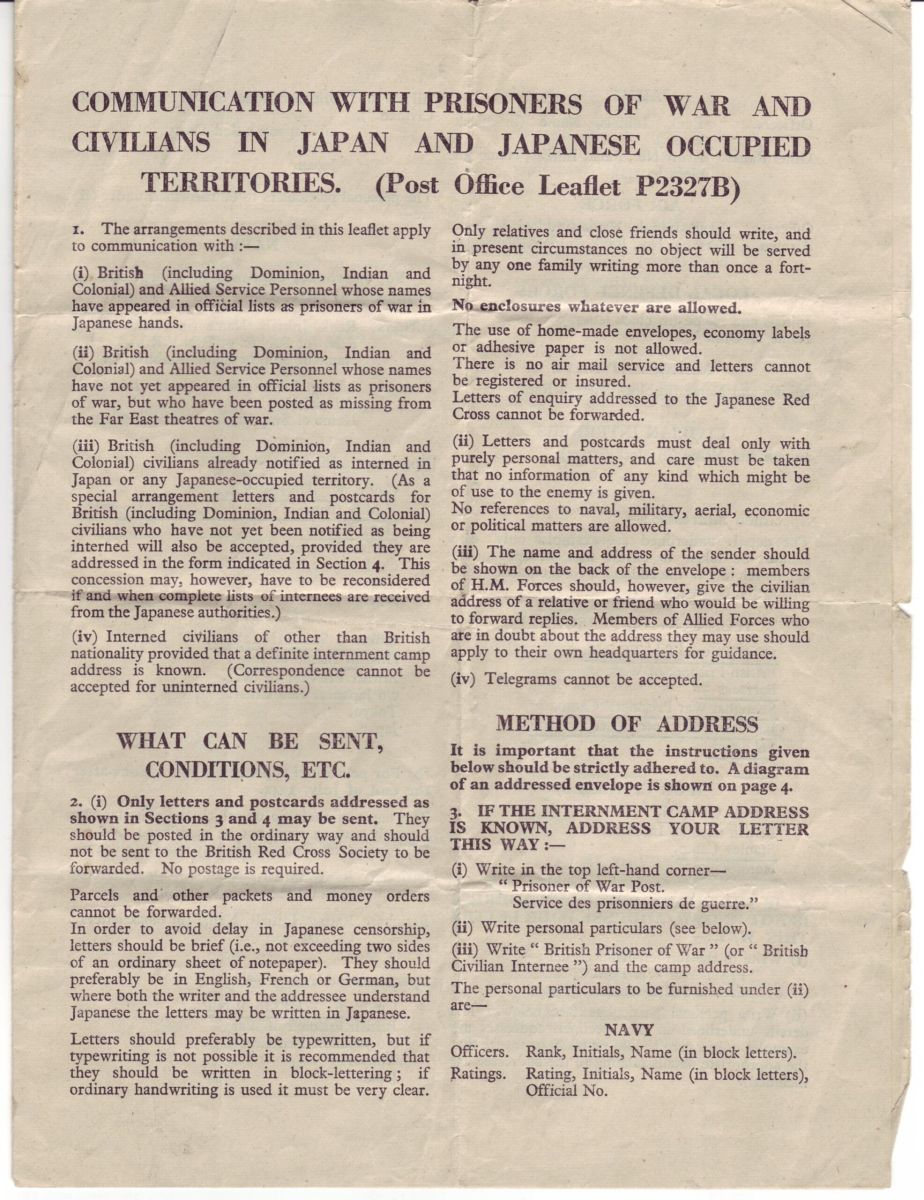

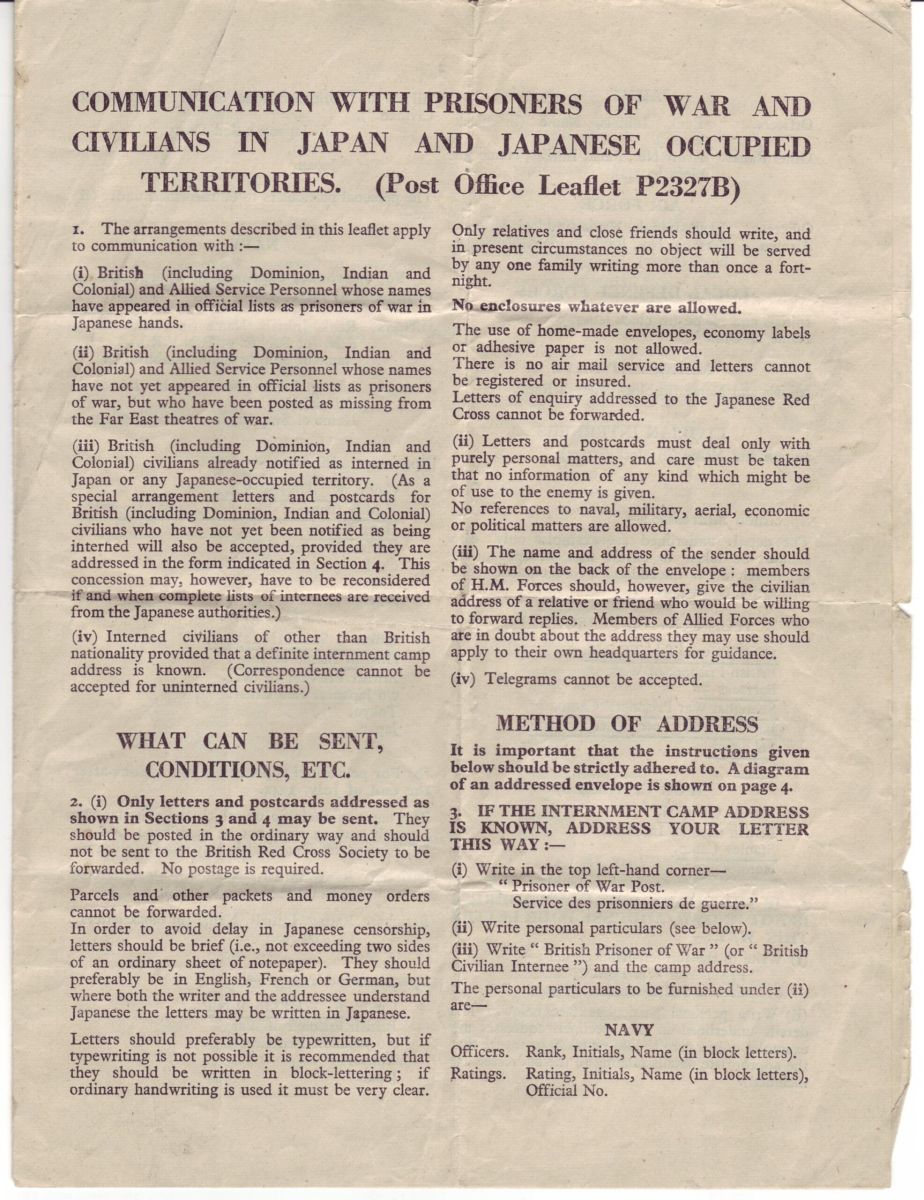

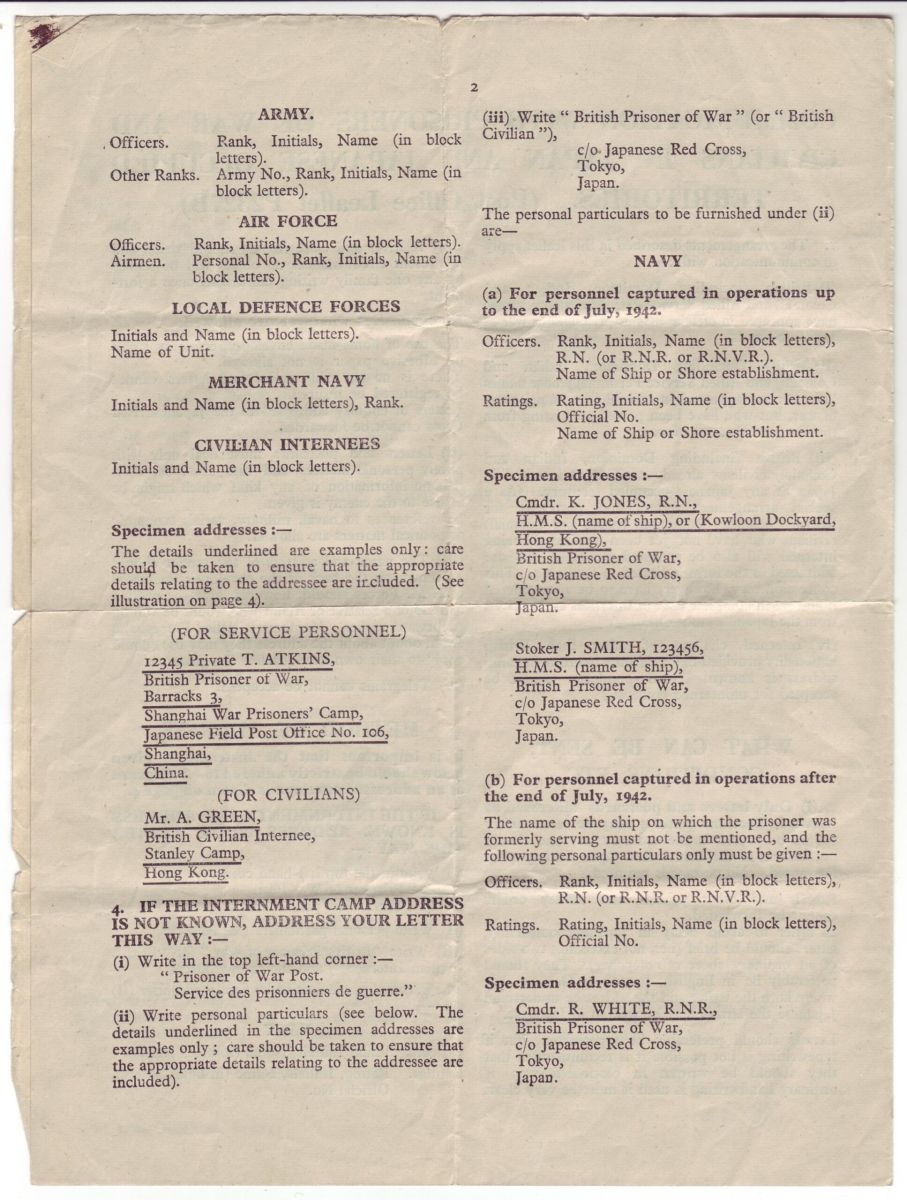

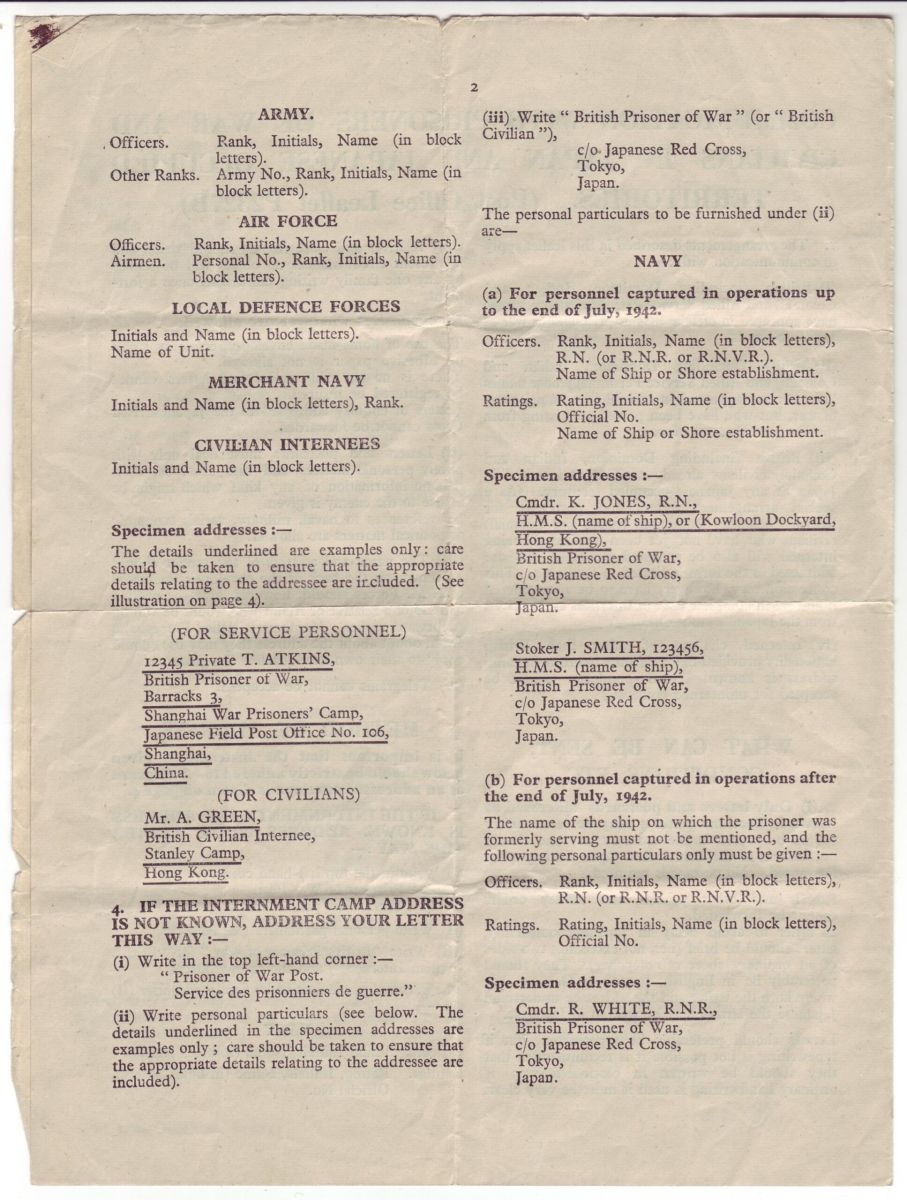

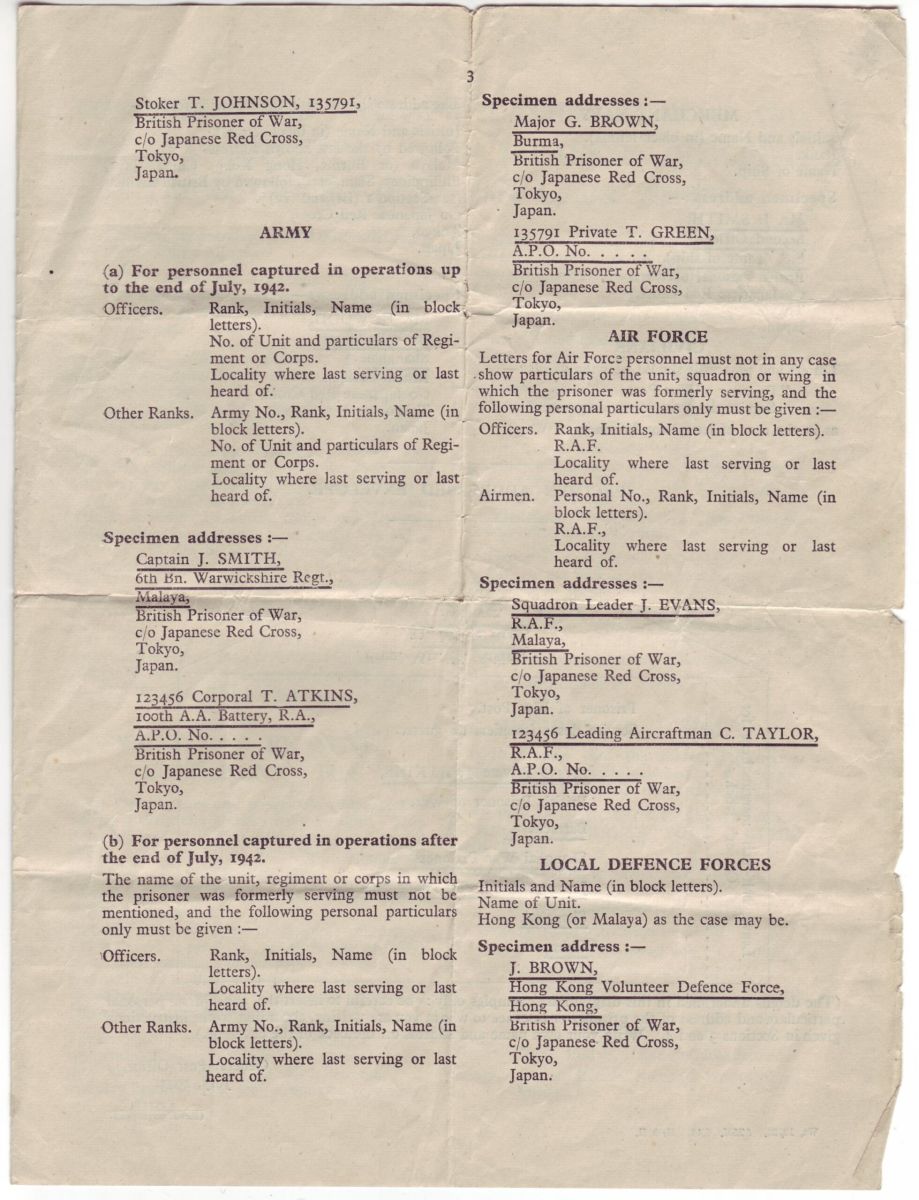

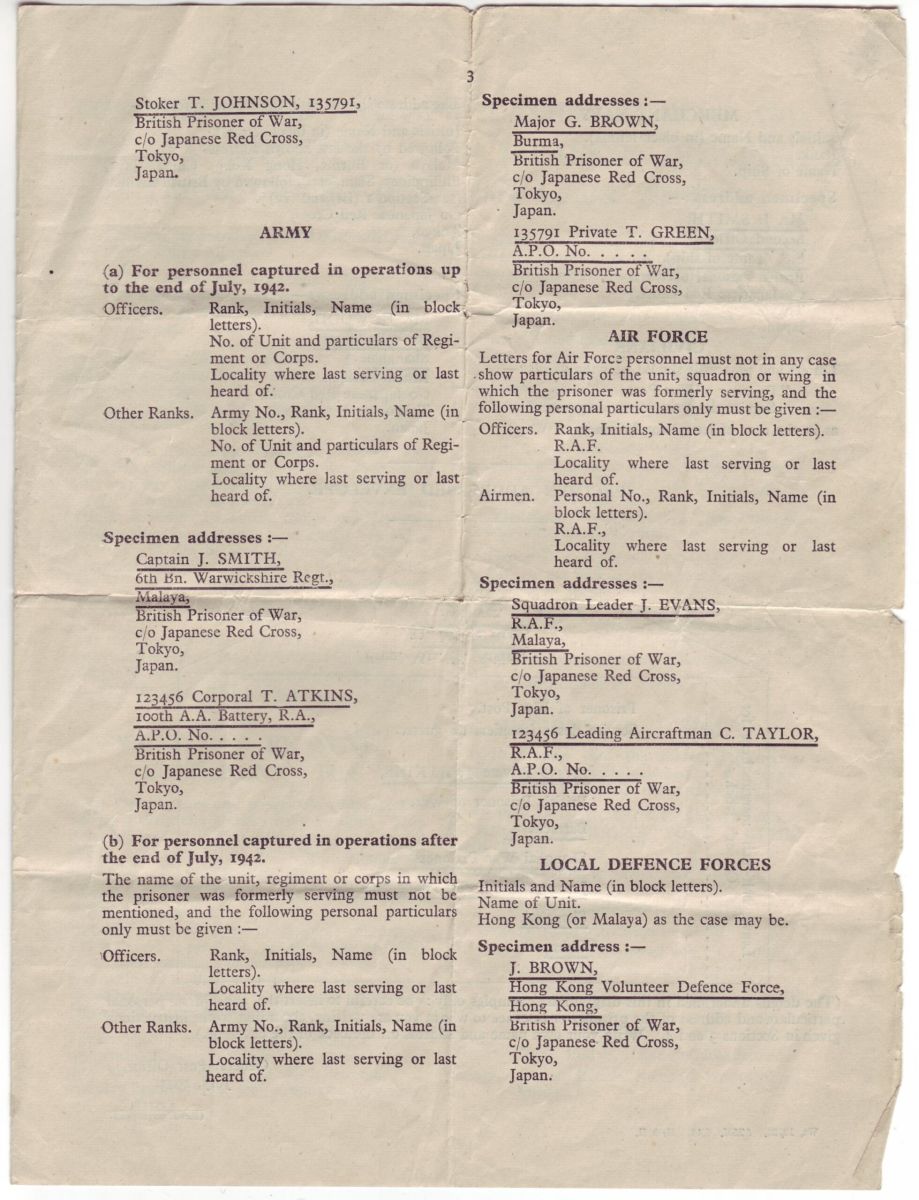

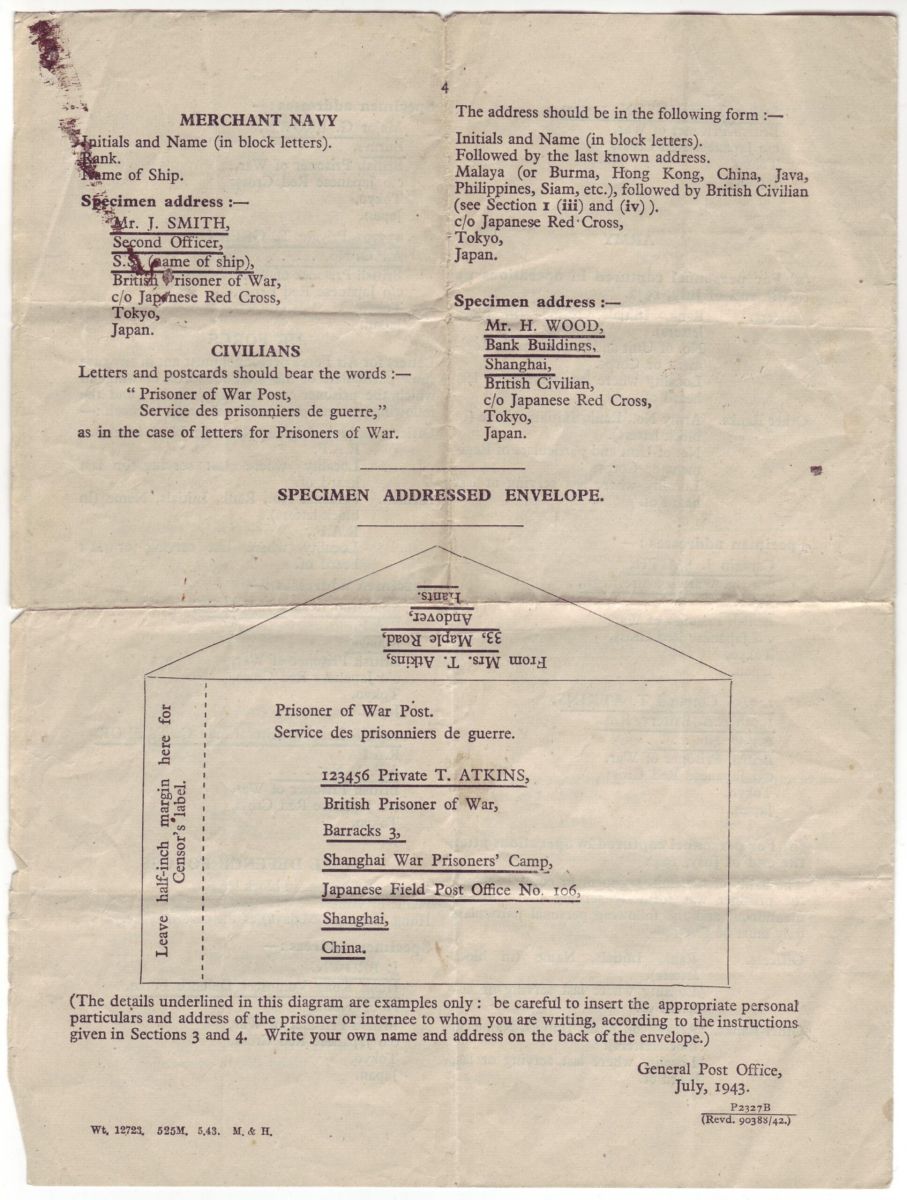

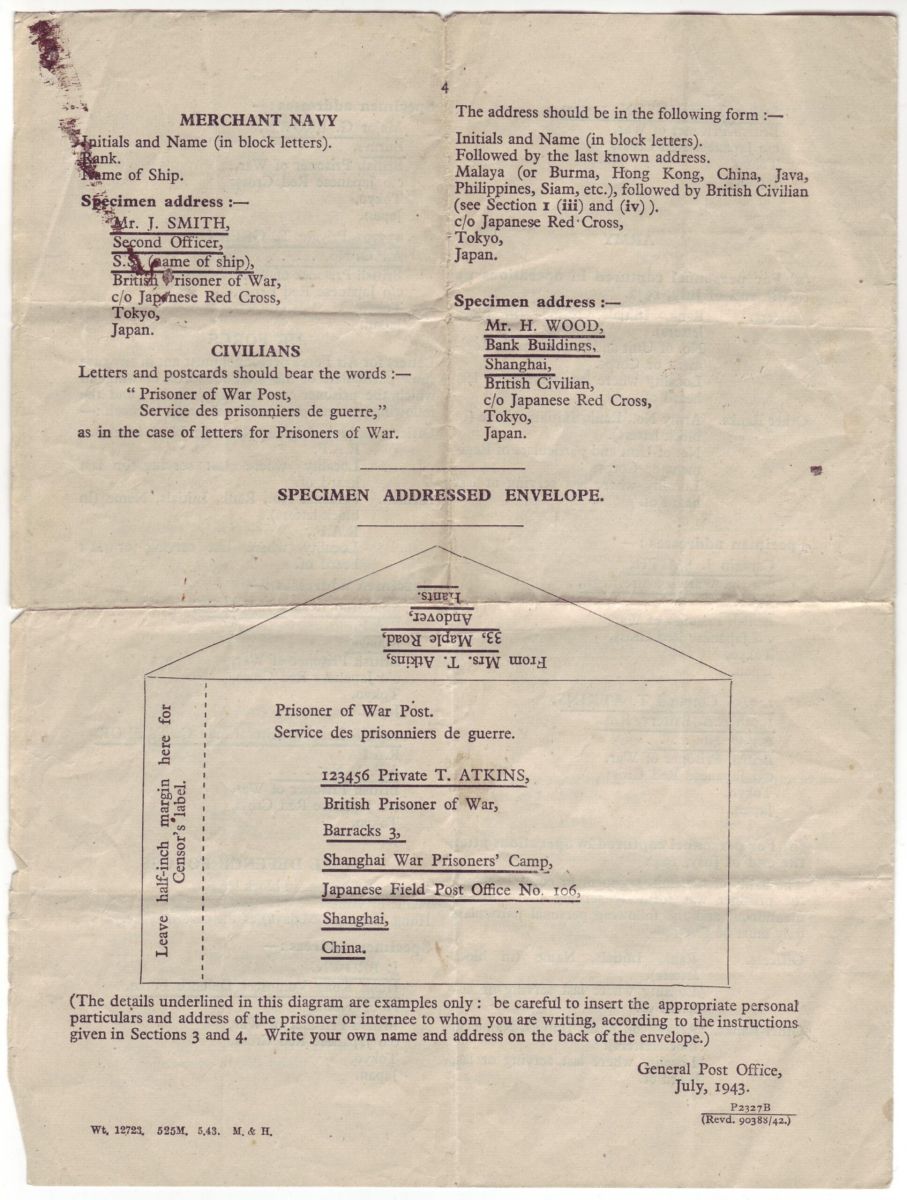

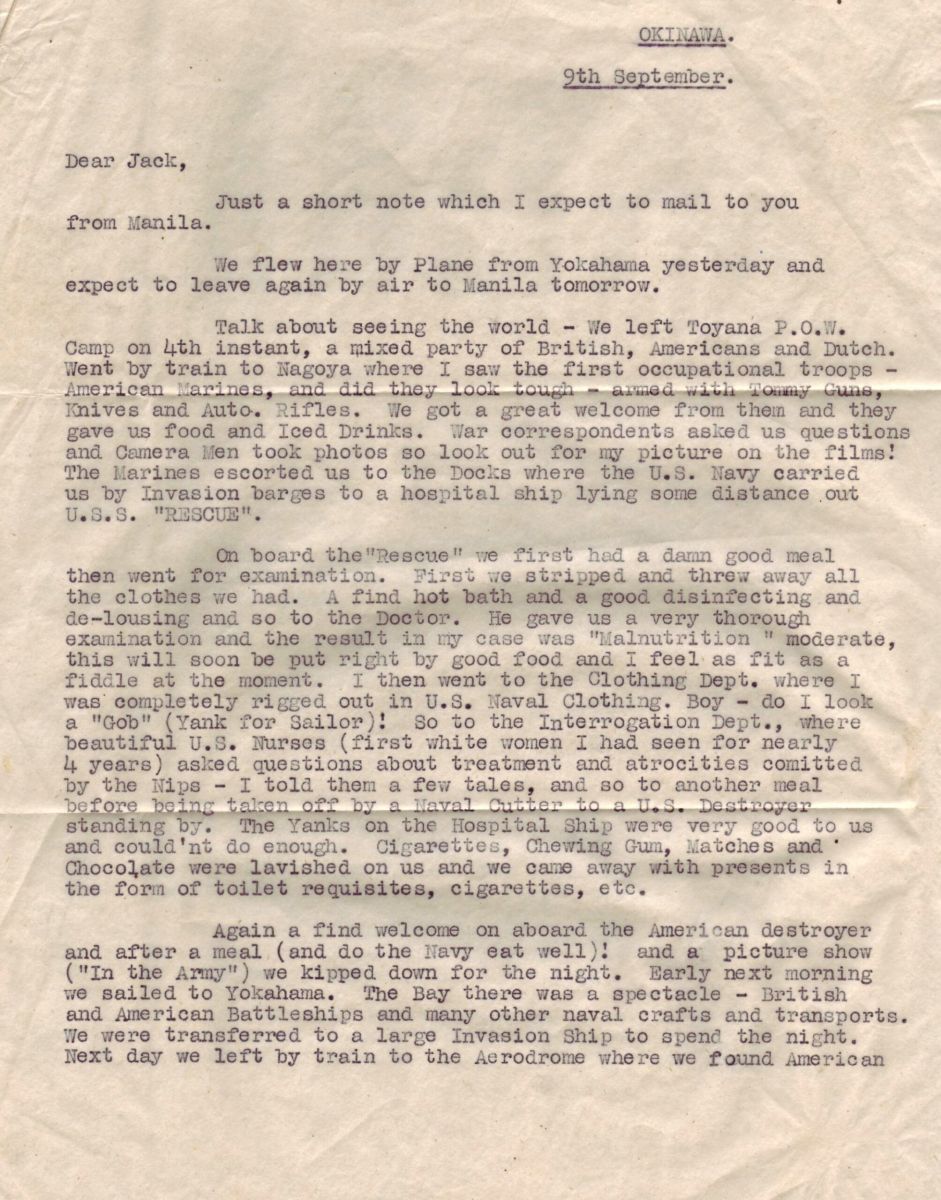

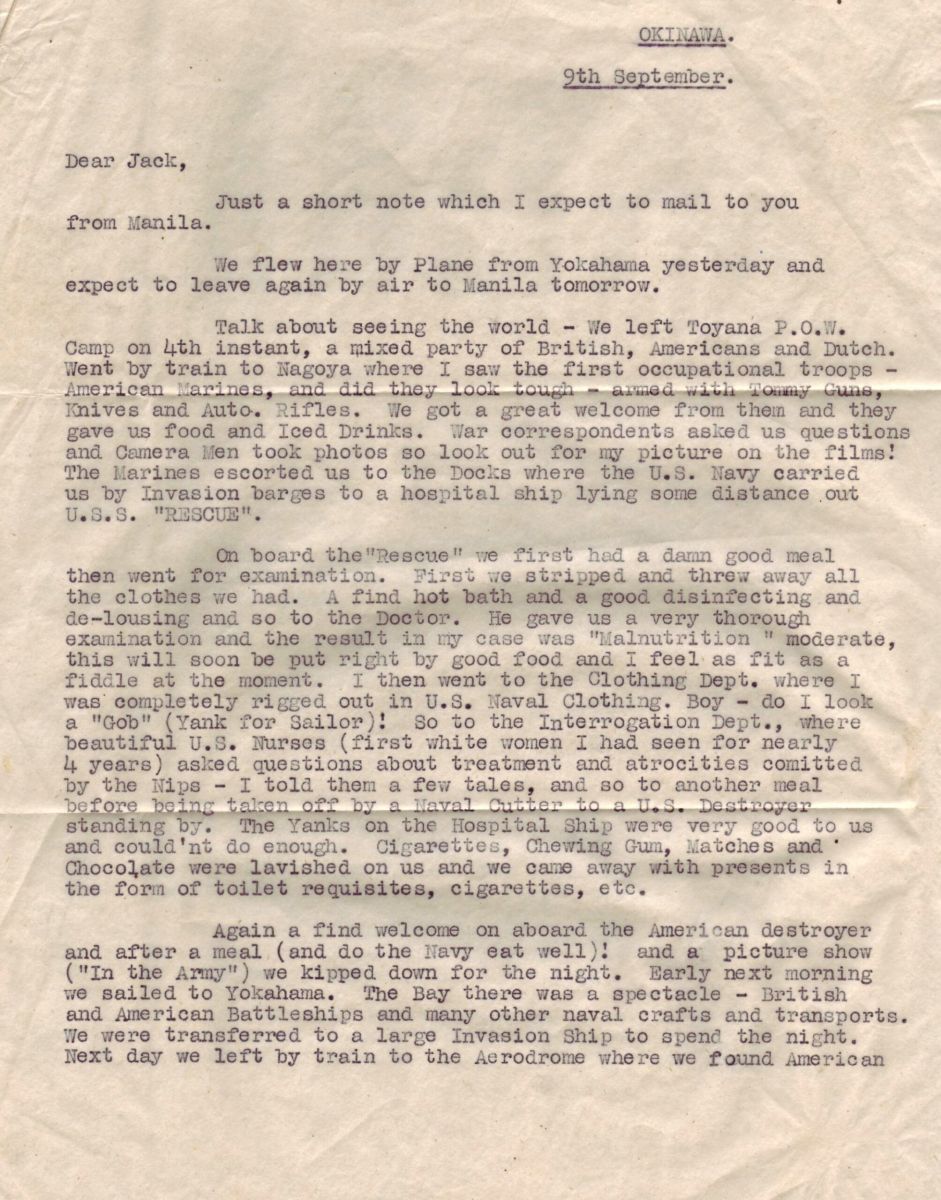

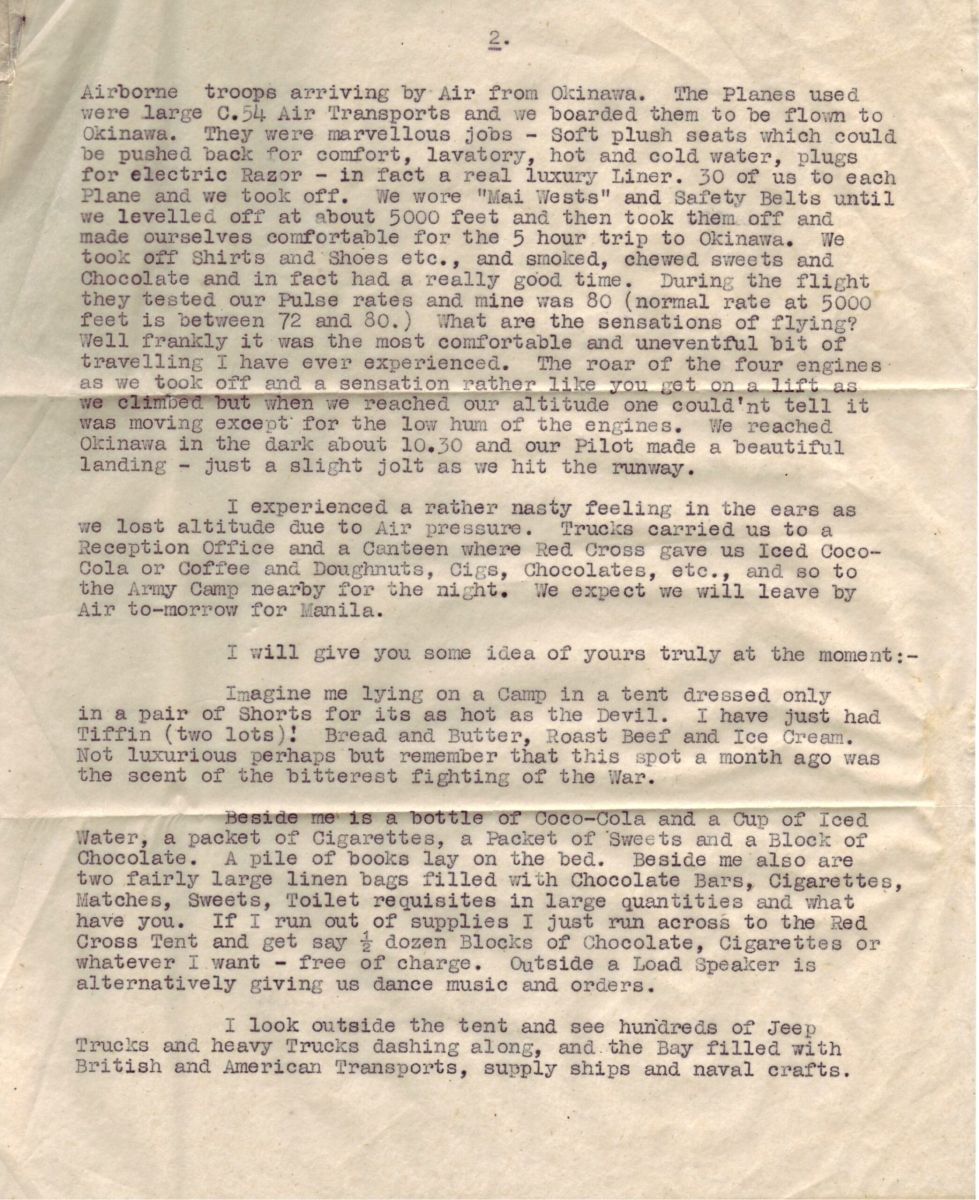

The documents which follow, include letters he sent during his journey home after his release from the POW camp and a long leaflet from the Post Office detailing how to communicate with POWs.

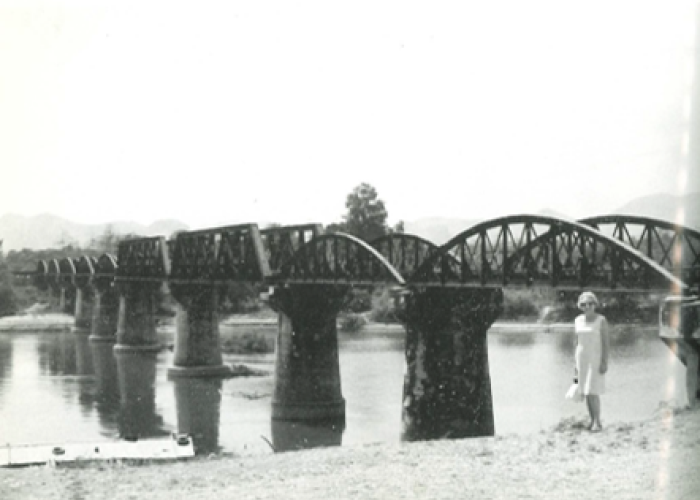

Alan Fryer visited Thailand together with a Thai friend, a few years ago and saw some of the places his father mentioned in his letters, notably the River Kwai and the Three Pagoda Pass. The latter, he discovered, is now a very civilised spot, very different from how his father described it back in 1945.

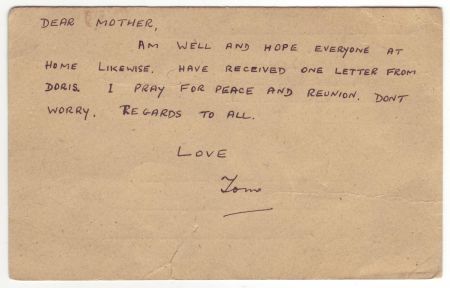

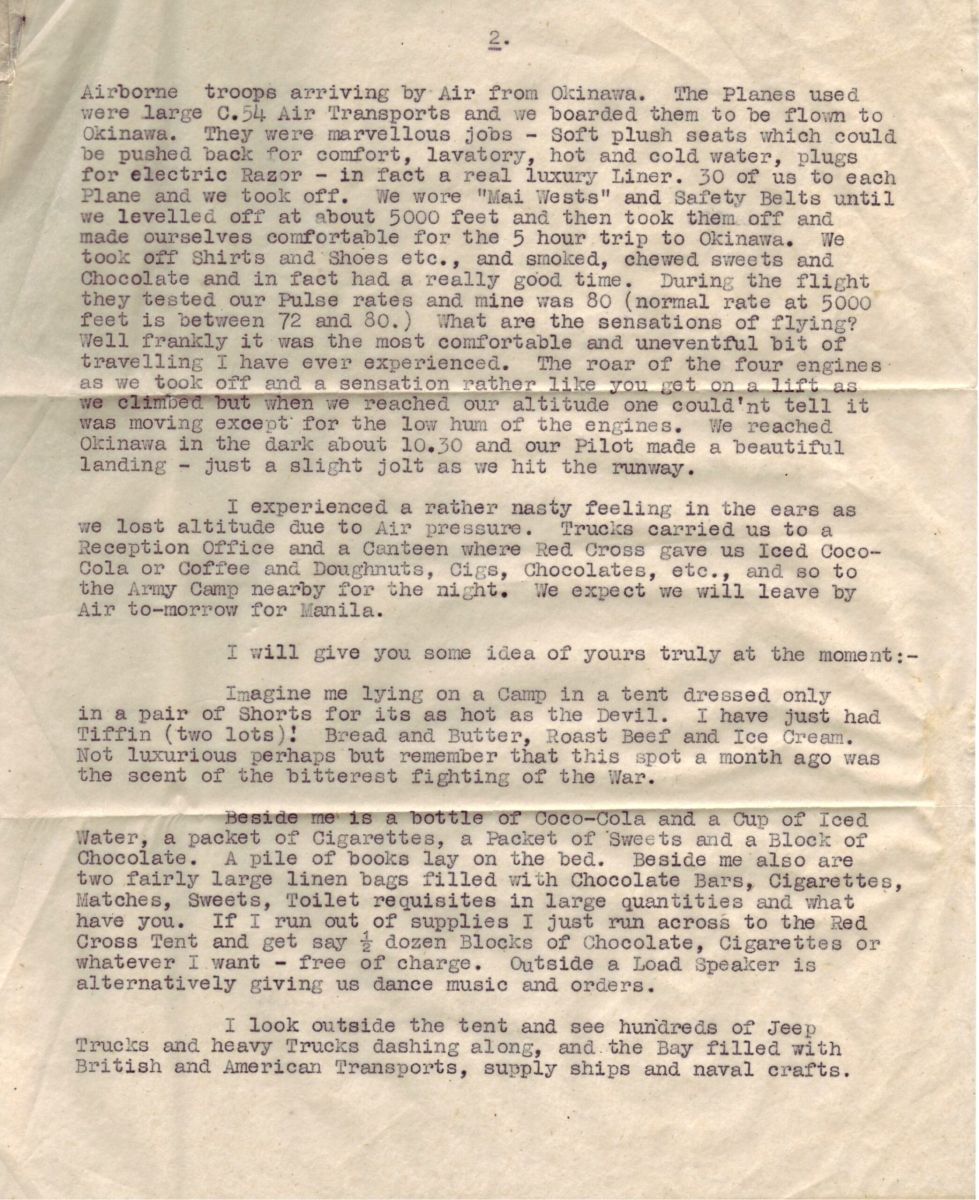

Photos Above: Letter from Thomas Walter Fryer to his mother, starting just 4 days after the surrender of the Japanese on 15th August 1945.

Photos Below: A long leaflet from the Post Office detailing how to communicate with POWs (likely a rather hopeless task!)

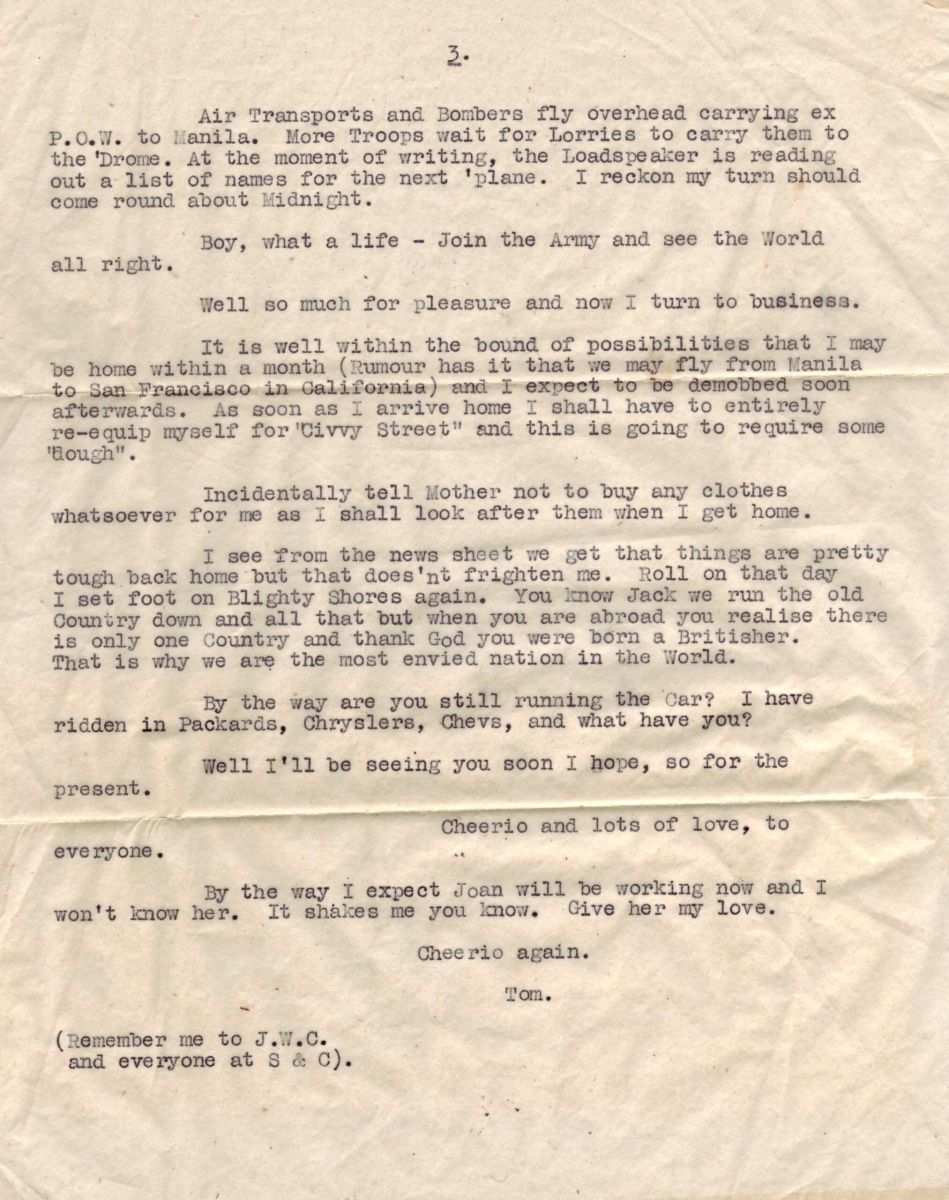

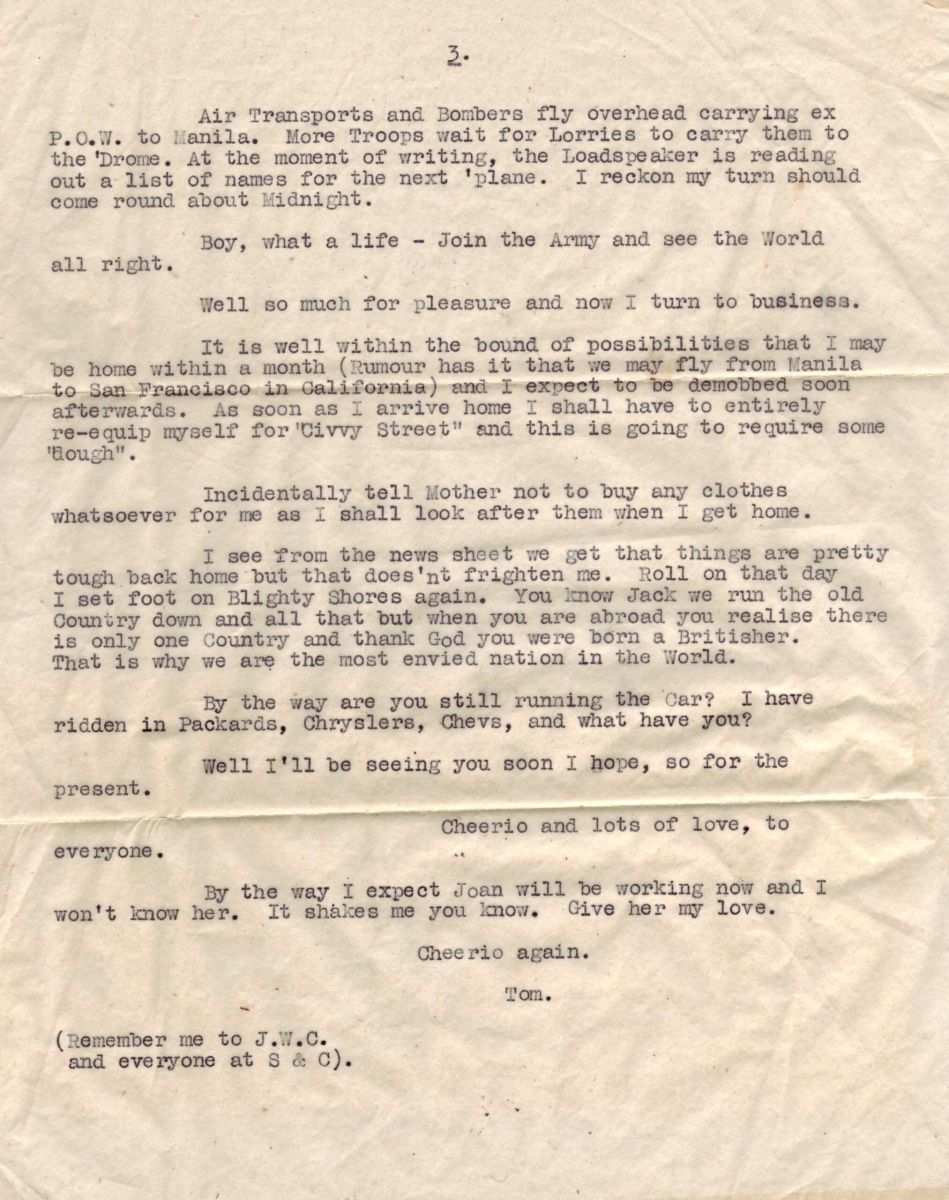

Photo Below: Letter from Tom to his brother, Jack, dated 9th September 1945

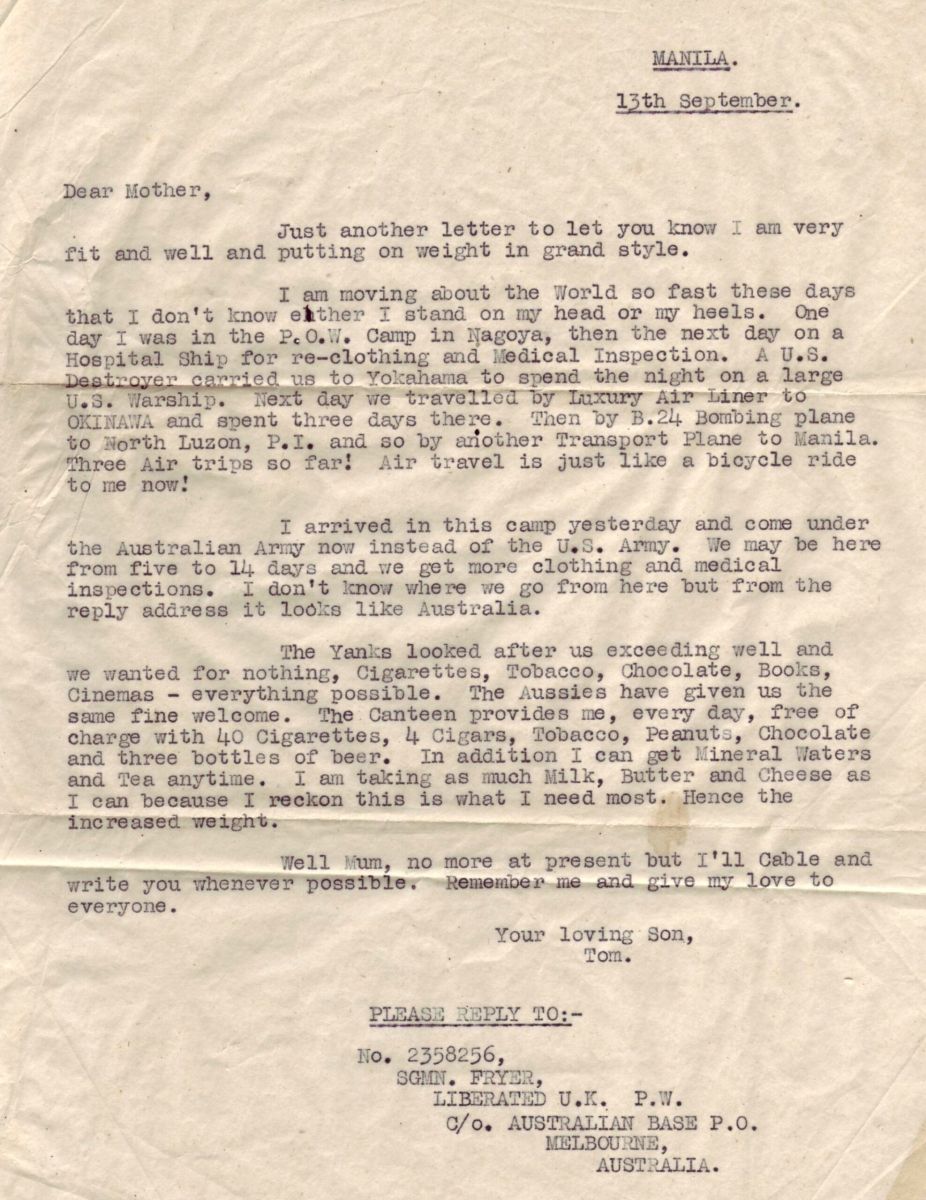

Photo Below: Letter from Tom to his mother, dated 13th September 1945

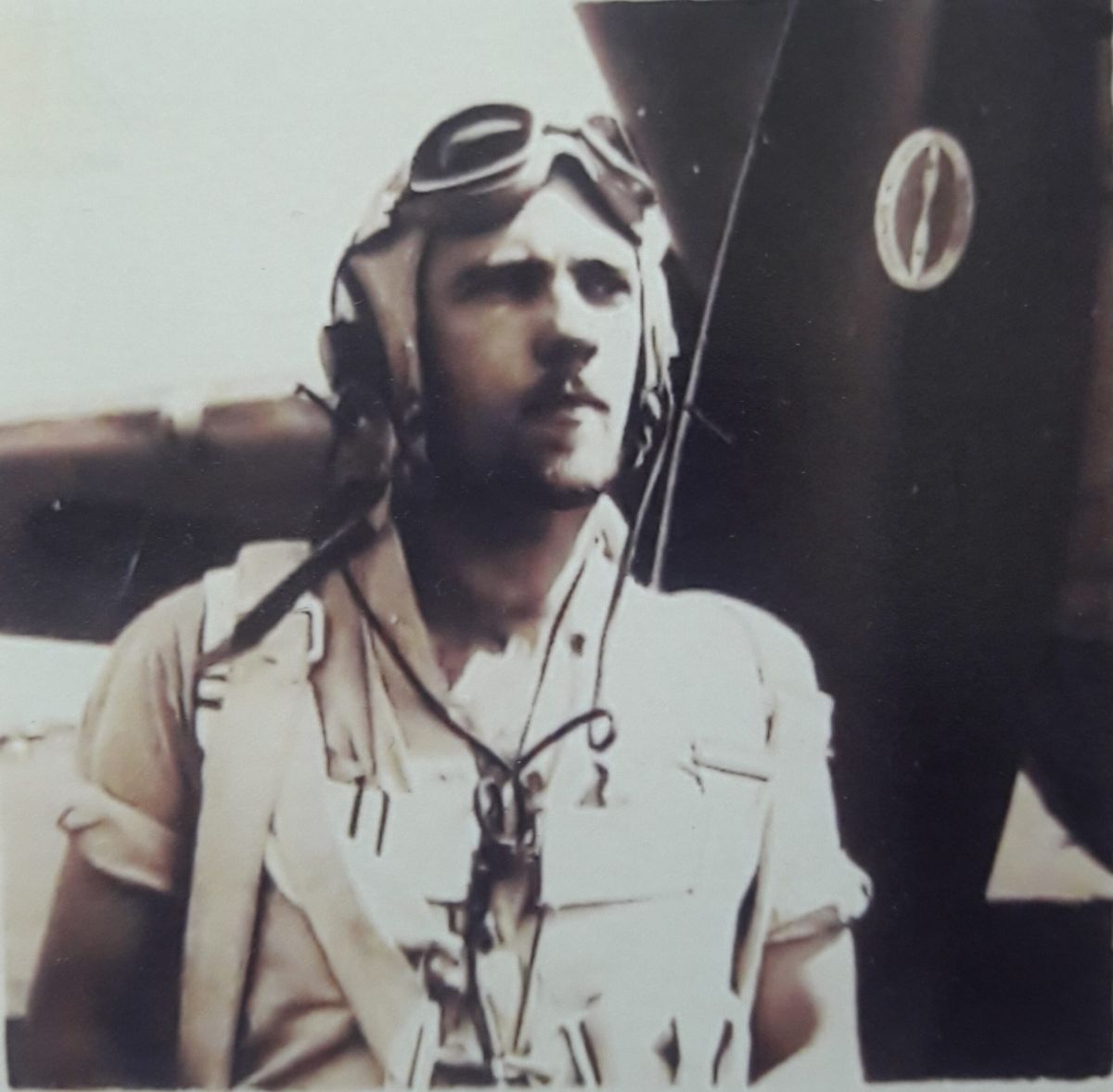

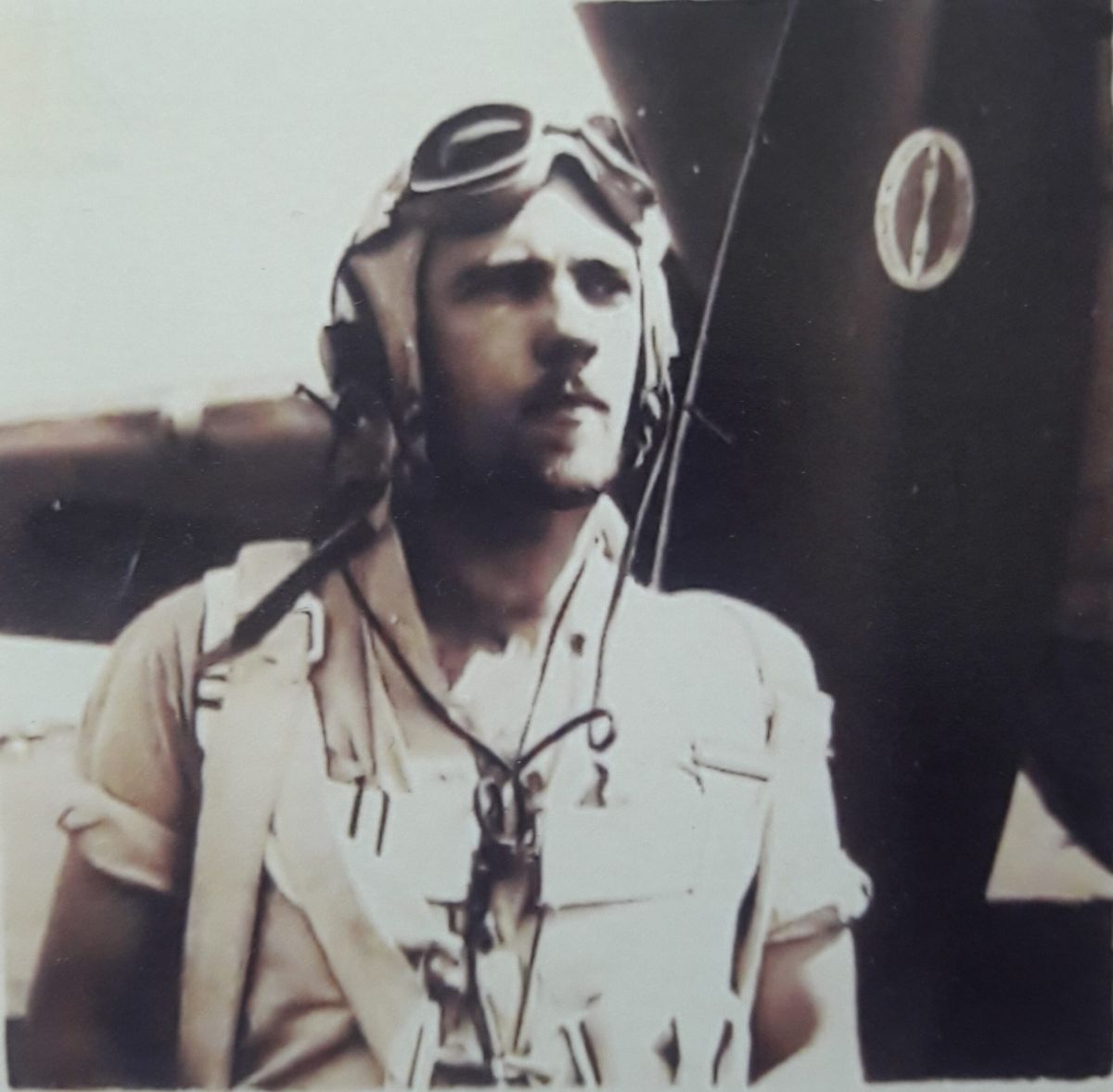

Lieutenant H. F. “Doc” Manget, Jr., TBM Avenger torpedo bomber pilot in Torpedo Squadron 27 (VT-27), US Navy

Lieutenant H. F. “Doc” Manget, Jr. served as a TBM Avenger torpedo bomber pilot with Torpedo Squadron 27 (VT-27). This photo was taken aboard the USS Princeton, which was tragically sunk during the Battle of Leyte Gulf on October 24, 1944. He and his fellow squadron members were forced to abandon ship and spent time adrift in the Pacific before being rescued by a U.S. destroyer. He was just twenty-two years old at the time. On VJ-Day, no one in the Navy celebrated more joyfully than those flight crews.

Lieutenant Manget, Jr. often recalled a memorable courtesy visit he and some squadron mates made to a Royal Navy cruiser. To their surprise, they found a fireplace and a bottle of whisky aboard. When the conversation turned to how to defeat the Imperial Japanese Navy, a Royal Navy officer offered this dry wisdom: “Outlive the bastards!”

Captain Kenneth Mitchell Hughes, The Manchester Regiment, later 65th Anti-Aircraft Brigade

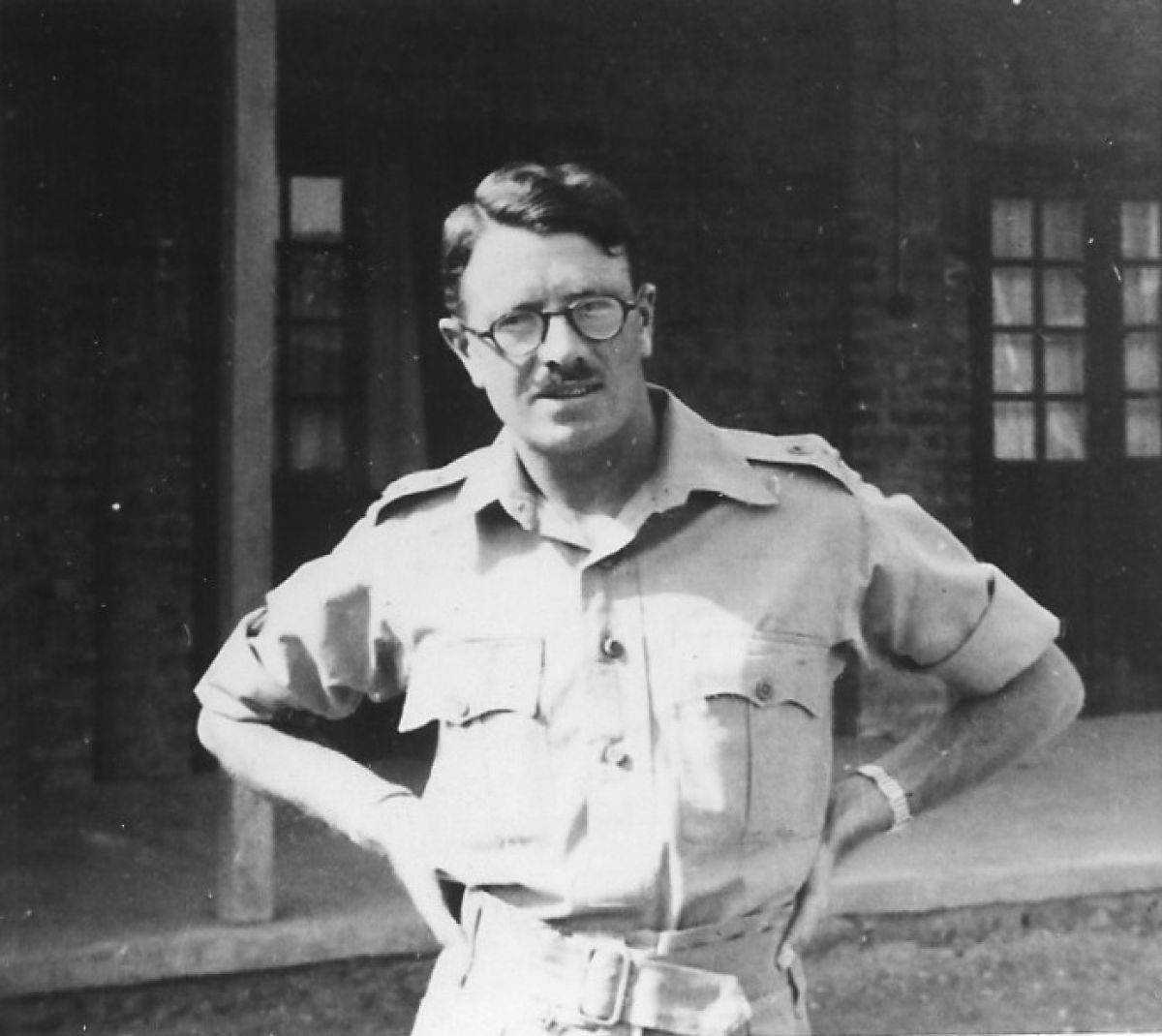

Photo Above: Kenneth Mitchell Hughes (1913-1945), is the uncle of VSC member, Peter Edward Hughes. Ken [seated] with colleagues taken most probably in August 1945.

One Man’s War: The Legacy of Kenneth Mitchell HughesInitially, serving in The Manchester Regiment, and later 65th Anti-Aircraft Brigade, Kenneth was taken prisoner by the Japanese during which he spent 14 months on the Siam/Burma Railway- the infamous route which ran alongside the River Kwai.

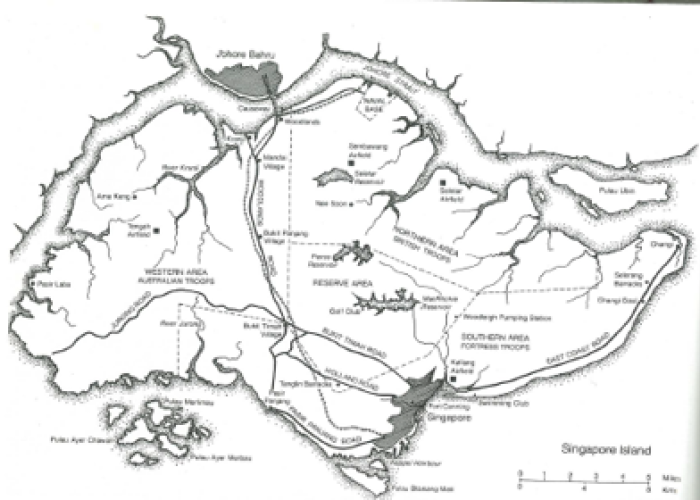

He joined The Manchester Regiment at the City’s TA unit in Ardwick Green, and was appointed a 2nd Lieutenant in November 1936. Four years later, as Captain, he was assigned to the 3rd Heavy Anti-Aircraft unit of the Royal Artillery. On 24th March 1940’ the men embarked at Southampton on HMS Dilwarra and six weeks later arrived in Singapore. Ken was given command of 21 Anti-Aircraft Battery. This battery protected the Naval base and civilian docks on the south side of the island.

The invasion of Singapore was expected from the south, so defences focused on the naval base. In early 1942, the surprise Japanese advance from the Malayan peninsula caught everyone off guard. After the mishandled surrender, all military personnel, including Ken, were captured—he spent the next six weeks in Changi Prison.

Recognising the challenge of managing so many prisoners, the Japanese began dispersing them. On 4 April 1942, 1,100 men—including 30 officers—were crammed aboard the Nisshu Maru, a notorious “hell ship,” bound for Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). The six-day journey was sweltering and cramped; prisoners weren’t allowed on deck and had to lie down the entire time in stifling heat.

Upon arrival on 10th April, they were housed in a camp opposite the dock gates on Rue Jean Eudel. The site, with four large huts, eventually held 1,664 prisoners, who were used as dock labourers and given minimal food. Despite the harsh conditions, prisoners made contact with the local French community. In a letter home, Ken described this period as the best part of prison life, thanks to the French secretly providing food, medicine, and news from the outside world.

The prisoners stayed in Saigon until 22nd June 1943, when a decision was made to move 700 men under Col. Hugonin from the docks to work on the Siam-Burma railway.

Photo Above: Looking towards the site of Kinsaiyok Jungle Camp 2 and the River Kwai.

Before the war, a railway linking Siam and Burma had been considered by the British but abandoned due to difficult terrain. After the Japanese occupation, however, the project was revived to support their Burma campaign and avoid the longer, riskier sea route. With thousands of prisoners under their control, the Japanese had ample forced labour. So in 1943, when progress lagged, they moved prisoners from the Saigon docks to Siam.

The group traveled via overcrowded boats up the Mekong to Phnom Penh, then by rail—often in open freight wagons where men sat on rail lines, afraid to sleep for fear of falling. After two nights at Nong Pladuk, they continued to Tha Sao by the River Kwai Noi. Arriving in the wet season, Ken was sent to Kinsaiyok Jungle Camp 2, where he would work on the Siam–Burma Railway for the next 14 months.

Following completion of the railway in April 1944, Ken was moved south to the Officers’ Camp at Kanchanaburi and then later to Pratchai. The Japanese separated the officers from the men. Their reason for doing this was that, should there be an Allied invasion, the Japanese believed that the men would be unable to organise themselves without the supervision of their officers.

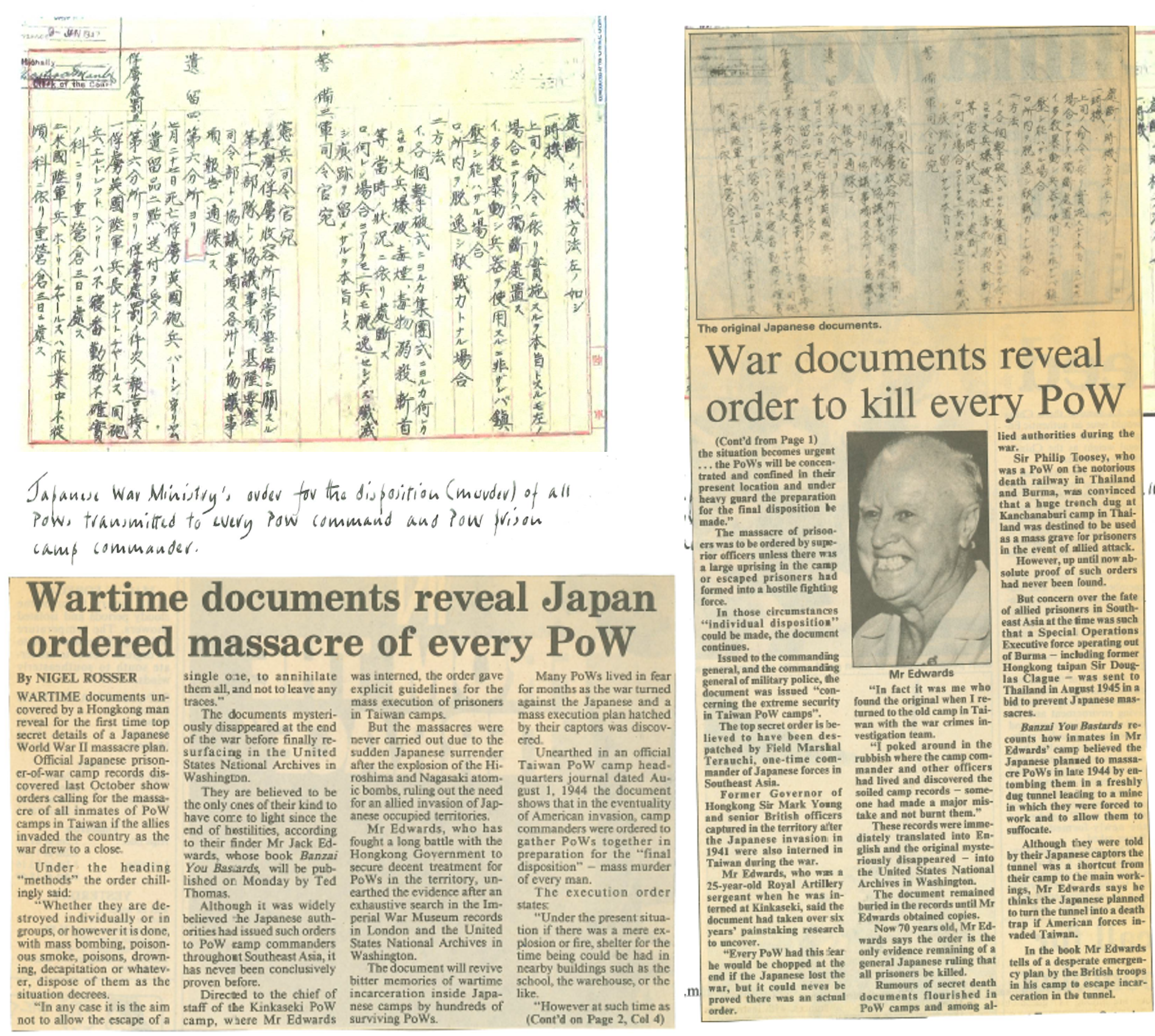

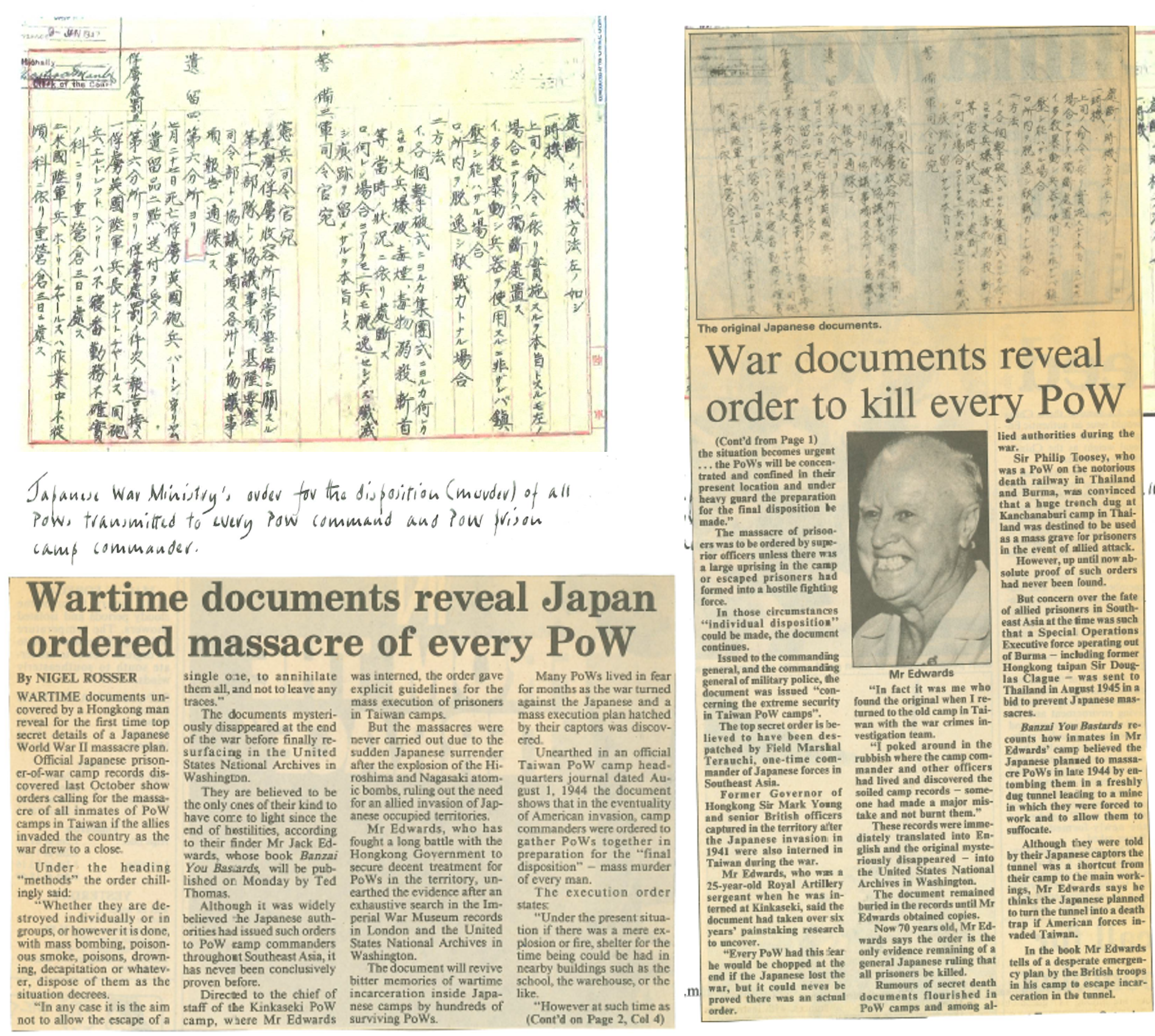

It was only following the dropping of the second atom bomb that Japan surrendered and the war in the Far East ceased. Had these bombings not taken place, the Allies would have invaded and it is likely that the Japanese would have carried out their threat to execute all their prisoners.

Before repatriation, POWs underwent health checks, so Ken was flown to Rangoon (now Yangon) and admitted to the Indian Field Hospital 52 at Rangoon General Hospital. In his final letters home, he said he was reasonably well, despite having had malaria three times and significant weight loss.

In spite of his poor condition, it is clear he was cheerful and looking forward to coming home. In one letter to his parents he wrote: ‘Please do not give me rice pudding, an apple pie would be something to look forward to’!

He had already been assigned to a ship due to depart Rangoon in November 1945, but his longed for journey home, did not happen. Regrettably he succumbed to Scrub Thyphus shortly after the ceasefire.

One of Ken’s close childhood friends gives another account of Ken’s last days. Whilst in hospital Ken visited some of his men in another part of the building, and was caught in a deluge. He developed a chill and, most likely due to poor resistance and already incubating Scrub Thyphus, his body could not combat the disease. He died on 23rd September 1945 and is buried in a Commonwealth War cemetery in a quiet corner of Rangoon. He was 32 years old.

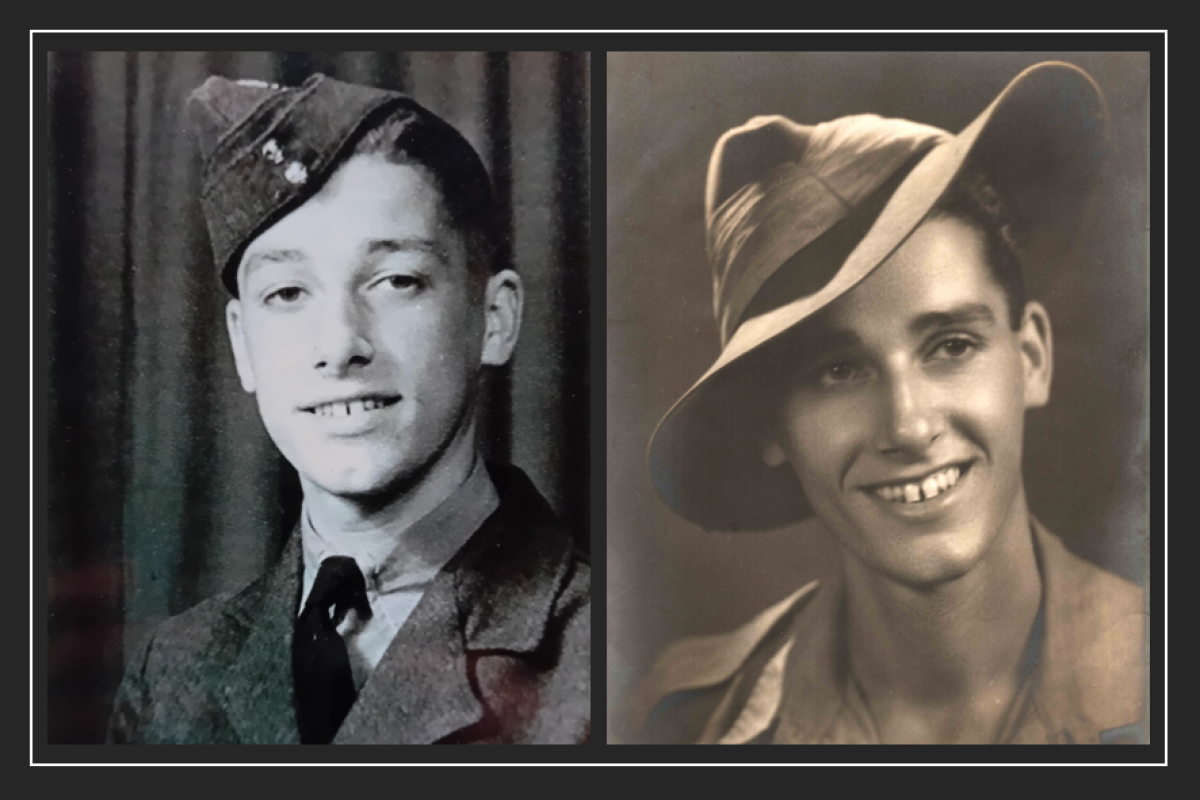

Lieutenant Ken Embleton, OC, 223 Line Construction Section

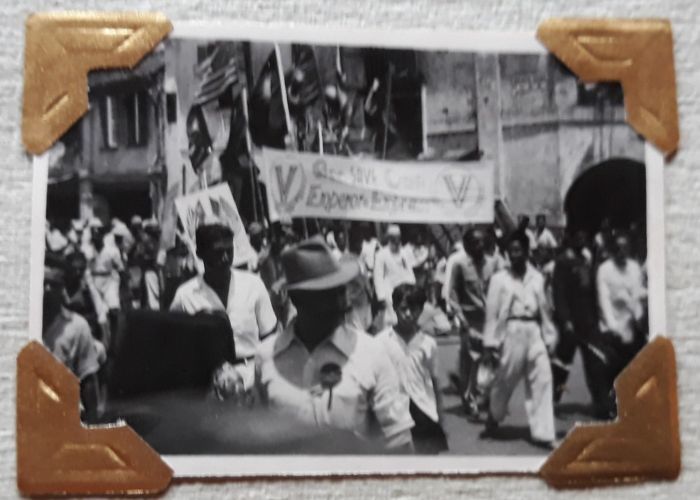

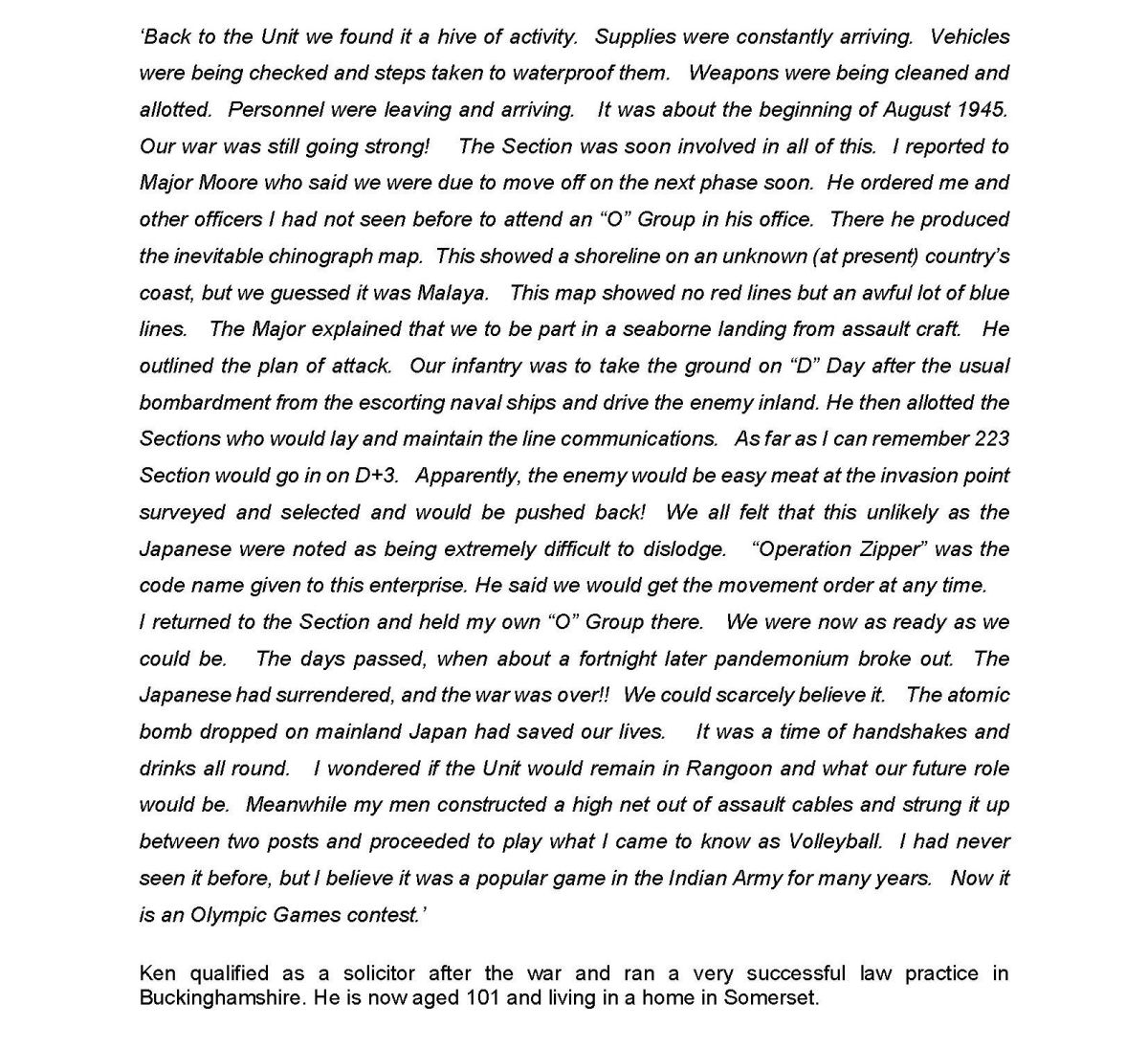

Lieutenant Ken Embleton was just 21 years of age, serving in Rangoon in August 1945. Here is an extract from his memoirs…

Thanks to Ken Embleton’s Godson, Charles Ackroyd, for this submission.

Corporal Cyril (Dave) Weightman, South Notts Hussars & 12th Para

Photo above: At the Ranville DZ, Cpl Cyril (Dave) Weightman MG Pl 12 Para is on the left. His Grandson managed to locate the exact spot due to the arrangement of the gliders in the photo and visited it and the area for the 80th Anniversary celebrations (and jumped there on the 50th Anniversary!)

Cpl Weightman is not wearing Puttees after landing up to his neck in water in a flooded field and spraining his ankle badly. (He didn’t want to wear just one and look silly!) He was dropped from a Short Stirling of 299 Sqn from Keevil airfield. He said the Aussie crew introduced themselves prior to the drop as they had never dropped Paratroops before! Not surprisingly then, he found himself dropped approx. 12 miles from the DZ he was supposed to be on. It must have been a difficult and dangerous journey to join up with the Bn. They are pictured eating tinned peaches and not drinking tea, as reported in the Daily Sketch. As tea was the stuff that British Soldiers were known to thrive on, it suited the narrative better at the time. (This Picture was on the front page.)

Cpl Cyril (Dave) Weightman served in the South Notts Hussars in N Africa, with the 1st Army, prior to volunteering with the Parachute Regiment. He subsequently joined 12 Para-jumping into Normandy, the Rhine and fighting in the Ardennes. His Battalion (Bn) was then shipped to the Far East in preparation for what they believed would eventually include the invasion of Japan. Until then, his Bn served in Java, Malaya, and Singapore.

Cyril’s grandson, Paul, particularly remembers the account of how his Grandad’s Bn relieved the garrison at Changi Gaol after the Japanese surrender. On seeing the very poor condition of the POWs, my Grandad’s CO ordered the summary execution by firing squad of the Japanese CO. He then ordered that if he found any of his men so much as offering a Japanese soldier a fag butt, that he would shoot that man himself.

Paul writes: ‘This may seem harsh and may be difficult to understand now, but I believe my Grandad, his CO and all the men of his Bn, who had already seen the concentration camps such as Belsen in Germany, were profoundly affected by what they had seen. I know this lived with my Grandad till the end of his days.’

Incidentally, Cyril’s grandson, Paul J Davis, served in the Parachute Regiment because of his Grandfather. His grandson has also been to Singapore to visit Changi and the Kranji War Memorial in 2004, where some of his Grandad’s comrades are buried.

A book entitled ‘Para Memories’ written by Yves Fohlen and Eric Barley about the men of 12 Para and their memories of the War, was presented to Paul by his Grandad. It includes specific references to their time in the Far East.

Cyril “Jim” Garrett, 356 Squadron, RAF

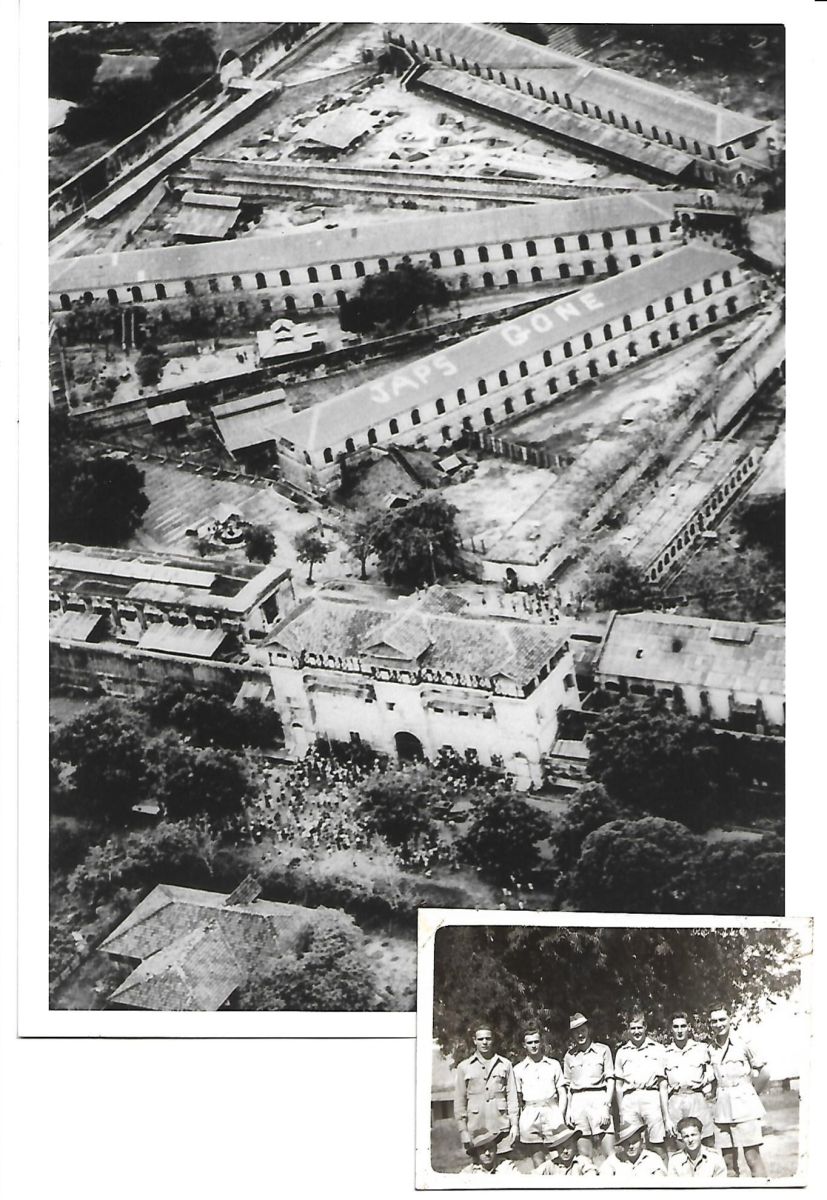

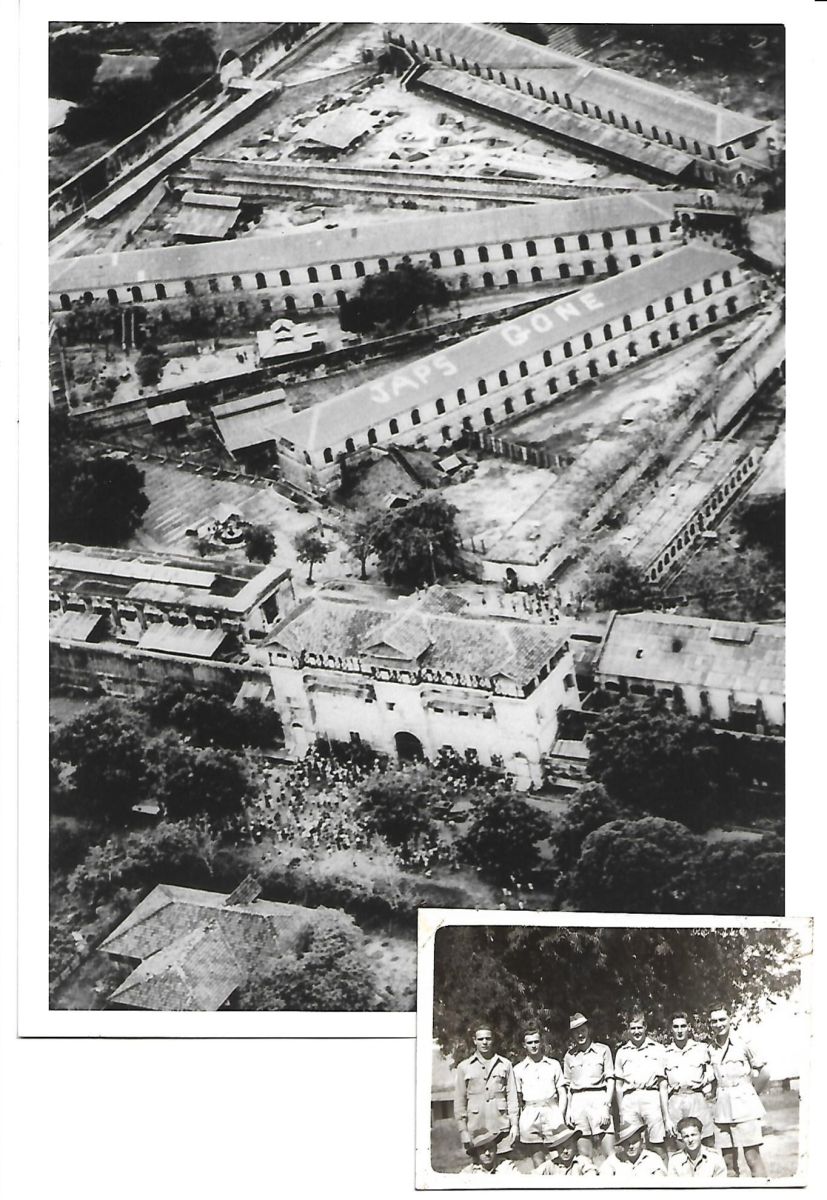

Photos above: Rangoon Jail | Inset: Jim Garrett is standing on the top row, first on the left

Cyril ‘Lucky Jim’ Garrett (1912-1975) was born in Cwm, a small South Wales mining community. Jim served as part of the RAF’s heavy bomber force flying Consolidated B-24 Liberators, deploying to Salbani, Northern India, with 356 Squadron.

One of the final missions took place on 3rd May 1945 — six Liberator aircraft took off from Jessore to drop medical supplies on Rangoon Jail, where 6,000 POWs were held by the Japanese. The jail was in the centre of the town and the drop was to be made from 400 feet to be accurate.

Only one aircraft reached the target and dropped the supplies. Five of the six aircraft were lost and 40 aircrew died. It was thought that these aircraft fell victim to bad weather, as there was no real Japanese opposition in the vicinity.

Remarkably, Jim Garrett was aboard one of those six aircraft and was among the few who returned—earning him the family nickname “Lucky Jim.” His story stands as a testament to the courage and sacrifice of RAF airmen in the Far East.

The returning crew brought back the news that the Japanese had evacuated Burma – the POWs having spelt out on the roofs of the jail — ‘Japs Gone’.

LAC Cyril Harry Benwell, RAF

Photo above: LAC Cyril Harry Benwell (1432624)—submitted by his daughter, Anne Saunders

LAC Cyril Harry Benwell (1432624), served with 155 and 273 Squadrons of the Royal Air Force. In January 1945, Cyril Harry Benwell was posted to Burma, joining a fighter unit just as the major Allied advance was gaining momentum—following the breakout from the “Imphal Box” and continuing through the length of Burma toward Rangoon. His unit provided vital fighter cover for the landings carried out by the 14th Army along the Burmese coastline, culminating in the assault and eventual capture of Rangoon.

Cyril remained in Rangoon for three months before sailing with a large naval force to Singapore, arriving in time for the formal surrender of Japanese forces—who were reportedly waiting at the quayside for the British fleet’s arrival.

Following the surrender, he stayed in Singapore for six months before being posted to Java (Indonesia). He eventually left the Far East in May 1946 and was demobilised the following month.

Cicero Rozario, Hong Kong Defence Volunteers

Photo above: Cicero Rozario is in the front row 2nd from the right.

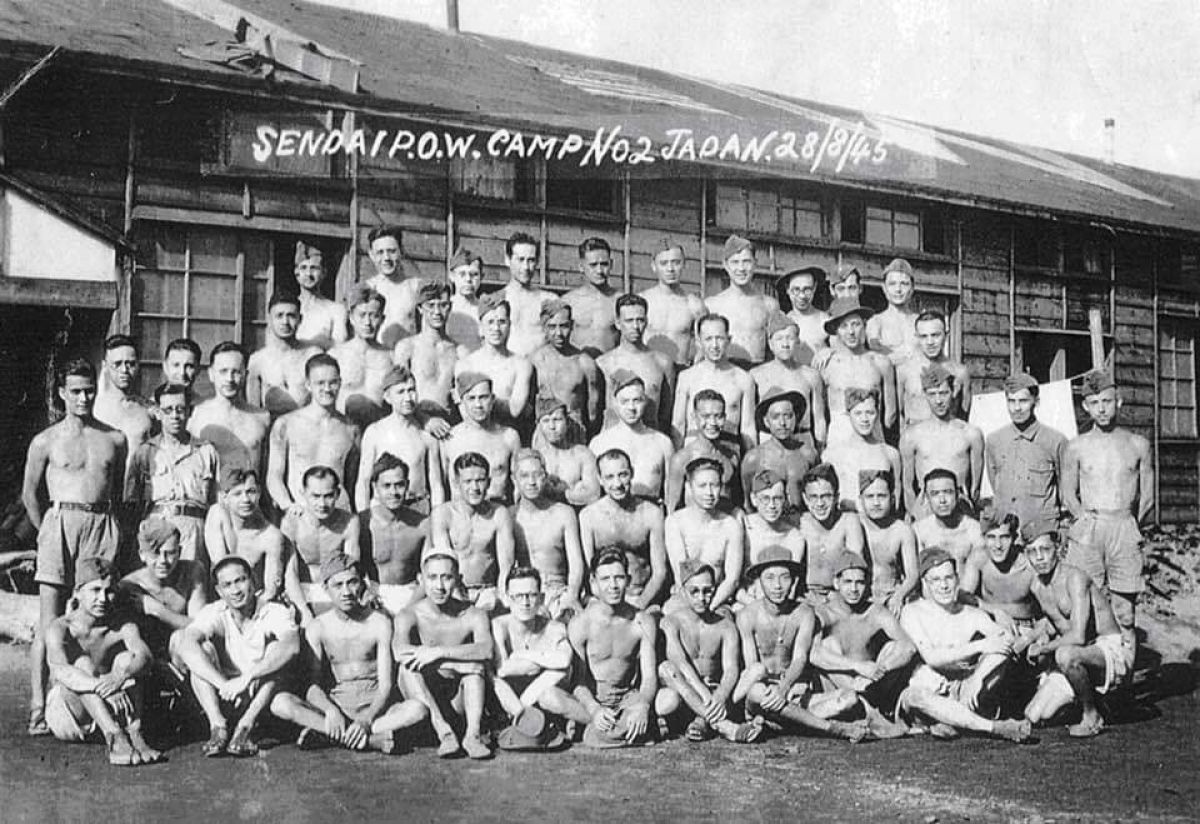

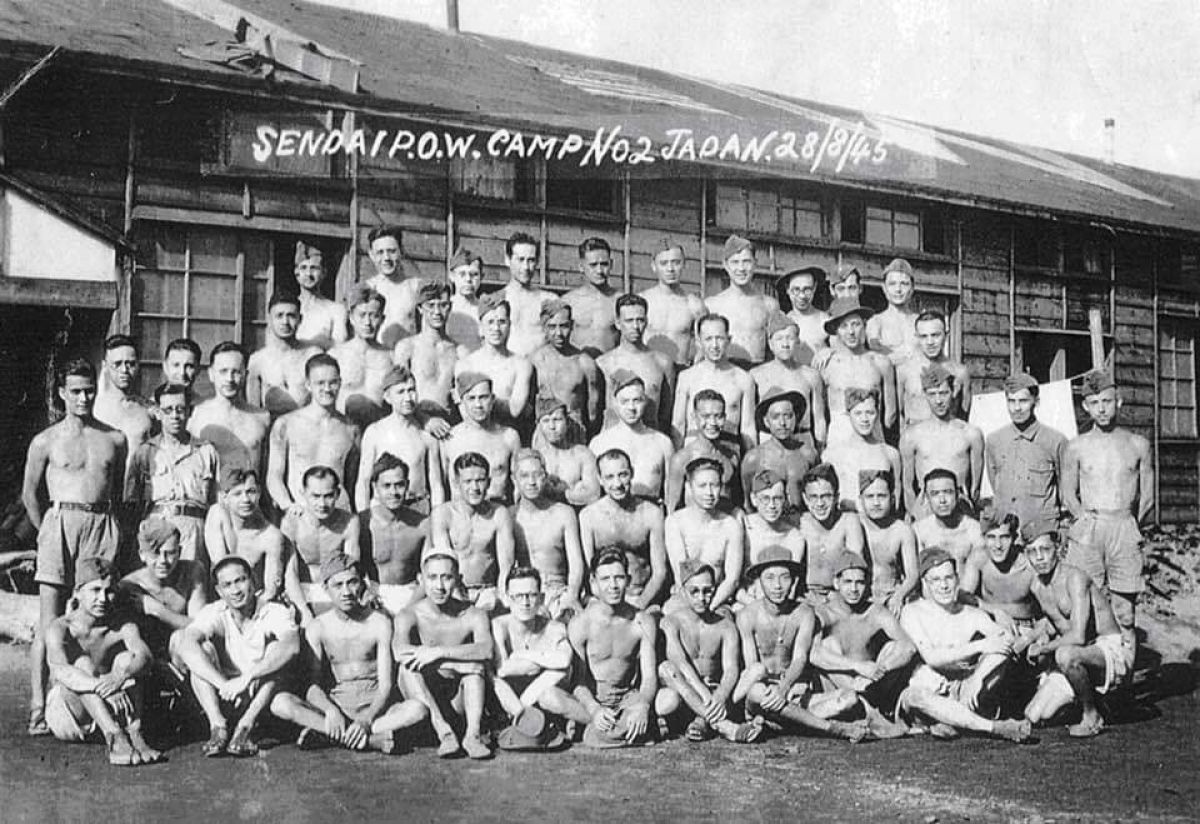

Patsy Jarvis’ uncle, Cicero Rozario, served with the Hong Kong Defence Volunteers, was captured by the Japanese and became a POW. He was first held at Shamsuipo and later transferred to Sendai, Japan. Though he wrote about his experiences, like many WW2 veterans he never spoke of them to his family. The memoirs of Cicero Rozario are attached below:

Experiences at Shamshuipo and Sendai POW Camps

After Hong Kong finally fell on 25th December, more than 10,000 prisoners—many from the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Force—were forced to march two miles from Star Ferry to Shamsuipo Camp. With only two ferries available, the journey took over twelve hours.

At Shamsuipo, prisoners were packed into Quonset huts, about fifty men to each. Conditions were harsh, with widespread outbreaks of scabies, dysentery, and diphtheria—many cases proving fatal. The camp housed a range of units, including the Royal Scots, the Middlesex Regiment, an Indian artillery unit, a Chinese Field Ambulance Section, and two Canadian regiments: the Royal Rifles and the Winnipeg Grenadiers.

The Volunteers were kept together in a single row of huts under the command of one sergeant major, maintaining a semblance of order amid the squalor.

Two of Patsy Jarvis’ father’s older brothers, Anthony Souza and Joseph Souza, were also prisoners of war in Japan. It’s thought that her Uncle Anthony was held in Osaka.

However, there’s uncertainty about where her Uncle Joseph was interned. He never returned to Hong Kong after the war, choosing instead to settle in London. Until he was hospitalised, he ran his own accounting firm in Paddington. A piece of wartime shrapnel had worked its way to his head, and sadly, he never recovered from the surgery to remove it. On her Mum’s side, her sister Carmen married Frank Molthen, who was also interned in Hong Kong: Old Doc Molthen

Colonel Philip Roland Gold, Royal Artillery

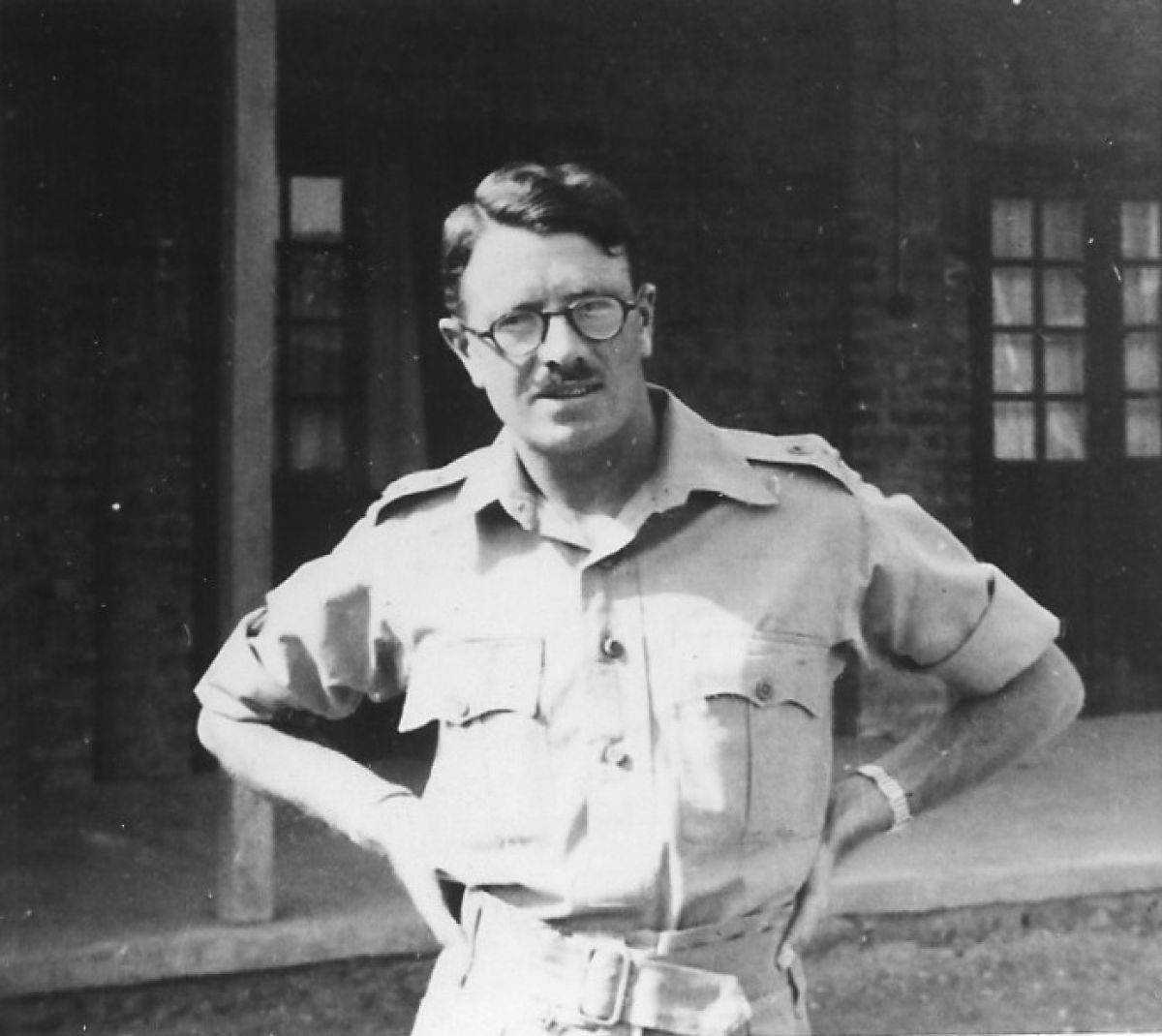

Photo above: Kirkee India March 1942 | Information submitted by his nephew, Mike Connell

Colonel Philip Roland Gold was one of the last British officers to escape from Singapore following its fall in February 1942. A career officer in the Royal Artillery, he served in numerous postings throughout his military life, ultimately finishing his service in Washington, likely in the capacity of a military attaché.

The above photograph of Philip Gold,was discovered in an album belonging to his brother, Stephen. This image appears to have been taken shortly after his dramatic escape. The full story of his wartime service and experiences is recounted in his personal memoirs, including fleeing Singapore (see link below):

Excerpt | Philip R Gold’s escape from Singapore

An extraordinary moment occurs in the final paragraphs of page 33, where Philip recounts a remarkable coincidence: a reunion with his brother Stephen during the final stages of his escape—an event that emphasises both the peril and poignancy of his journey.The contents page of his full memoirs (link at end) reveals the breadth of P R Gold’s military career, much of which was dedicated to the Royal Artillery. In researching Philip’s life, his nephew, Michael Connell, reached out to Philip’s eldest son, Anthony Gold, who provided further insights and directed him to a website chronicling some of the individuals involved in the Singapore escape: | Widdington Village

At the bottom of the article on that site is a group photograph of the escapees (see below):

Photo above: Philip Roland Gold is the third figure from the left

The Gold family has deep roots in the village of Widdington, where all three siblings—Philip, Barbara (his sister and the mother of the narrator), and Stephen—grew up. Stephen and his family later settled nearby in Debden, just over the hill.Captain TKW Atkinson, RN Dockyard in Singapore | Missing believed killed 1942

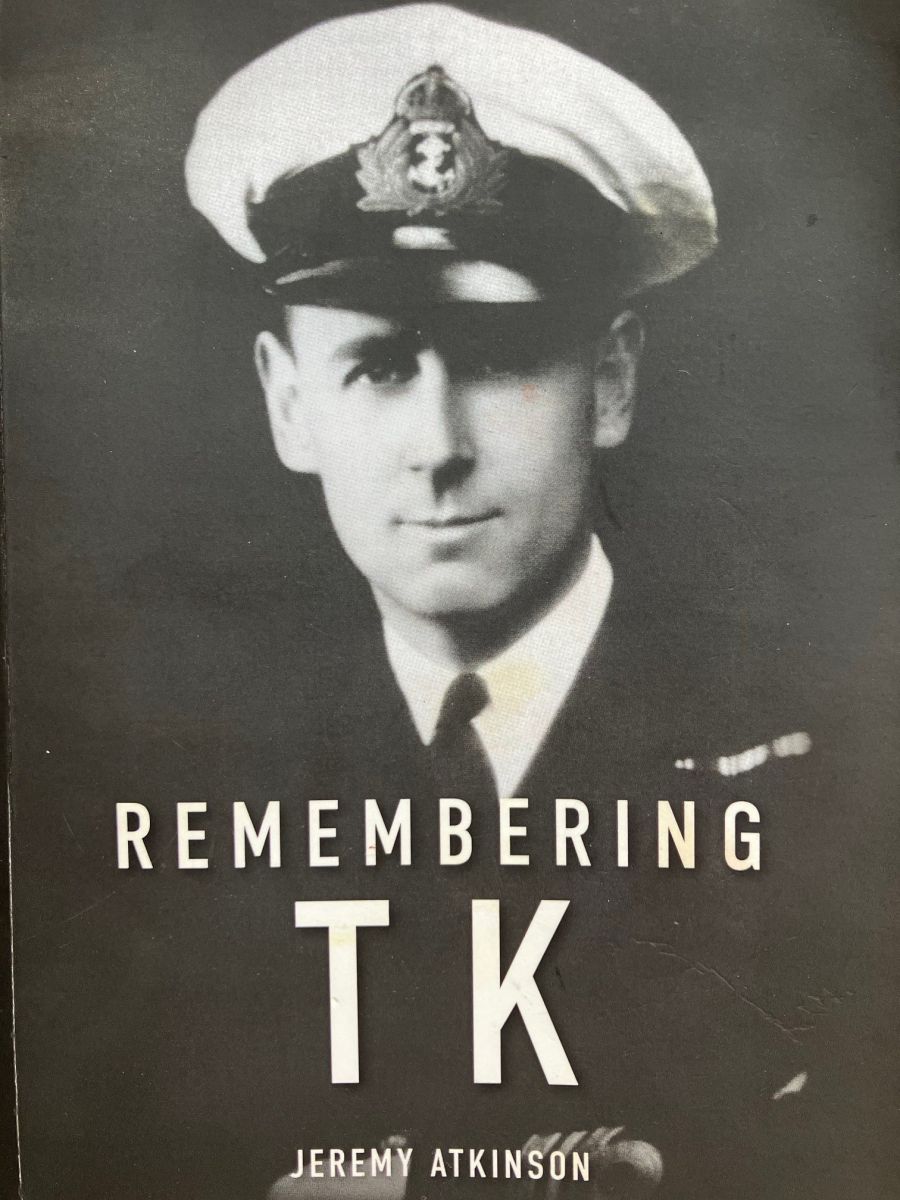

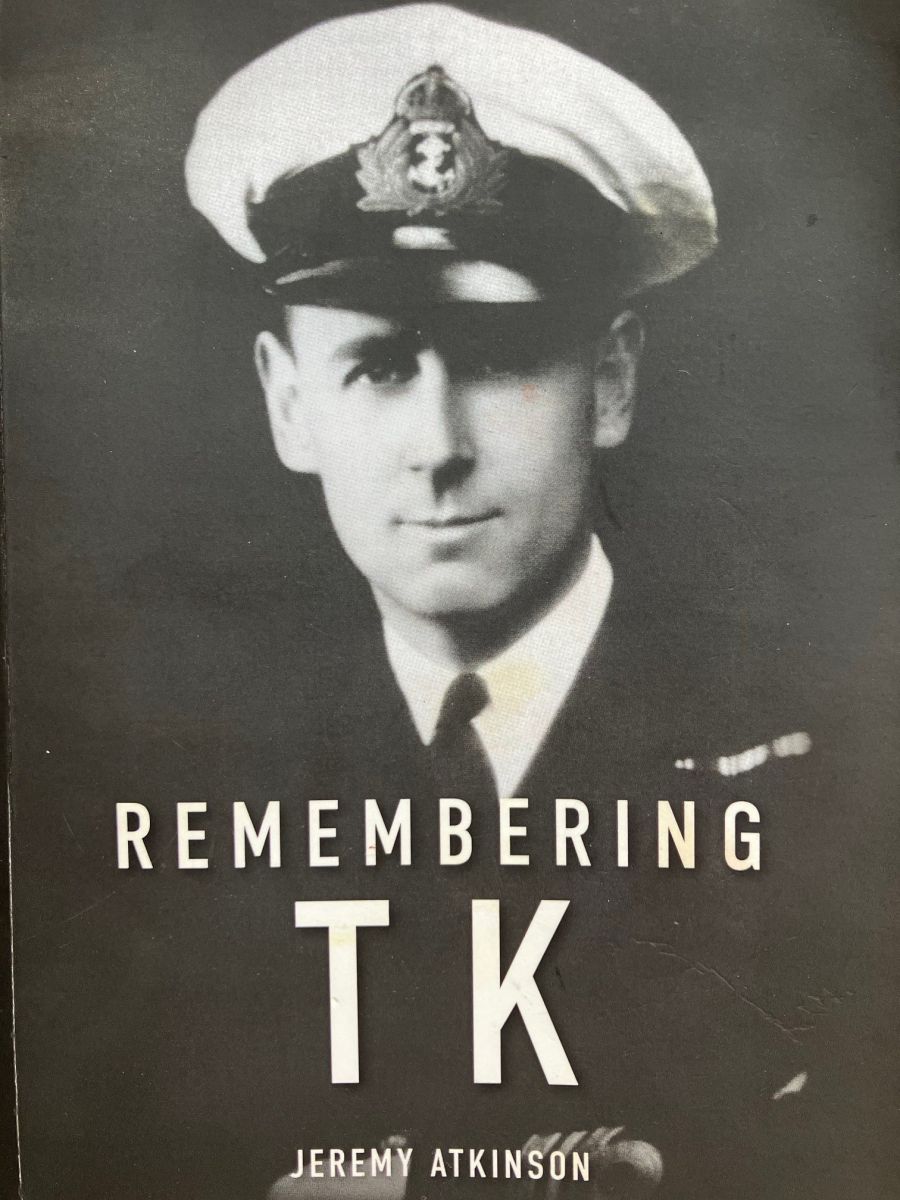

Photo above: Thanks to Rupert Atkinson, grandson of Captain TKW Atkinson for this submission.

TKW Atkinson [“TK”], was born on January 26th, 1902. He joined the Royal Naval College in September 1915, and had a 27-year career in the Navy. His last job was as Captain of the (RN) Dockyard in Singapore, from May 1941.

On the north side of the island, the Naval base was largely evacuated on 31st January 1942. Two weeks later, “TK” was one of the last senior officers to leave Singapore, before it was surrendered to the invading Japanese forces.

However, “TK” never reached the intended destination of Batavia (Jakarta), since the tug he was on was shelled by Japanese vessels on 15th February, killing Rupert’s grandfather and others- although there were survivors.

Not knowing his fate for several years, his wife, Rupert’s grandmother, continued to write to him via the Red Cross regularly, in the hope that he might be alive and receive them.

VJ Day was marked by “TKs” 14-year old son, Jeremy Atkinson [JJWA] – who later also served in the Navy – by lighting candles around the family home in Hampshire. When the official report of “TK”’s death was released, it was dated 30th October 1945.

After the passing of his mother, and greatly aided by the opening of the official papers by the then PRO, after a 50-year embargo in 1993, JJWA began to piece together an account of his father’s final weeks and days, drawing heavily on the large volume of letters “TK” had sent home from Singapore.

In 2022, JJWA self-published the book Remembering TK. Sadly, JJWA himself passed away peacefully on 2nd June 2025.

Temporary Acting Sub Lieutenant(A) RNVR, Richard (Dick) Martin

Photo above: Temporary Acting Sub Lieutenant (A)RNVR, Richard (Dick) Martin—submitted by Paul Botterill re:his wife’s late father

Richard (Dick) Martin, Temporary Acting Sub Lieutenant (A)RNVR, was a veteran of the naval war in the Pacific. He joined HMS Deadalus (Lee on the Solent) as a Naval Airman in 1942 and after passing his killick’s board went to America on the old Queen Mary to start flying training the following year.

Promoted to Midshipman on gaining his wings he completed operational flying training at Pensacola, Florida, before joining a Corsair squadron and embarking on the escort carrier, HMS Slinger. At the time the US Navy only operated Corsairs from ashore and thought the Brits were crazy flying them from carriers.

After working up in the Clyde in December 1944, HMS Slinger departed for Sydney to join the British Pacific Fleet, the largest fleet of Royal Naval ships ever assembled.

On arrival in Australia he was transferred to 1836 squadron embarked in HMS Victorious to replace a pilot lost during the attack on the Pelambang oil refinery on Sumatra.

In late April the fleet sailed from Sydney to support the American assault on Okinawa and Dick flew his first combat operation over Formosa, now Taiwan, attacking Japanese airfields, on the 8th May, as Europe was celebrating VE-Day. With one short period of respite in Guam, Victorious remained in continuous operations, until 15th August VJ Day.

Altogether Dick flew 31 combat missions and was Mentioned in Dispatches. His final sortie was against the Hitachi factory near Tokyo on 10th August, the day after the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki but before Japan agreed to surrender. He was 21 years old. Victorious sailed back to Sydney then home, arriving in Pompey on a cold, grey November day.

There was no band to greet them, no waiting dignitaries, no ceremony whatsoever. The hostilities only men were given a rail warrant, their discharge numbers and sent on leave to await demobilisation. Dick was but one of many but he never forgot those with whom he served on the far side of the world, who never came home.

Major Grahame Vivian, 4th Battalion of the 8th Gurkha Rifles, India.

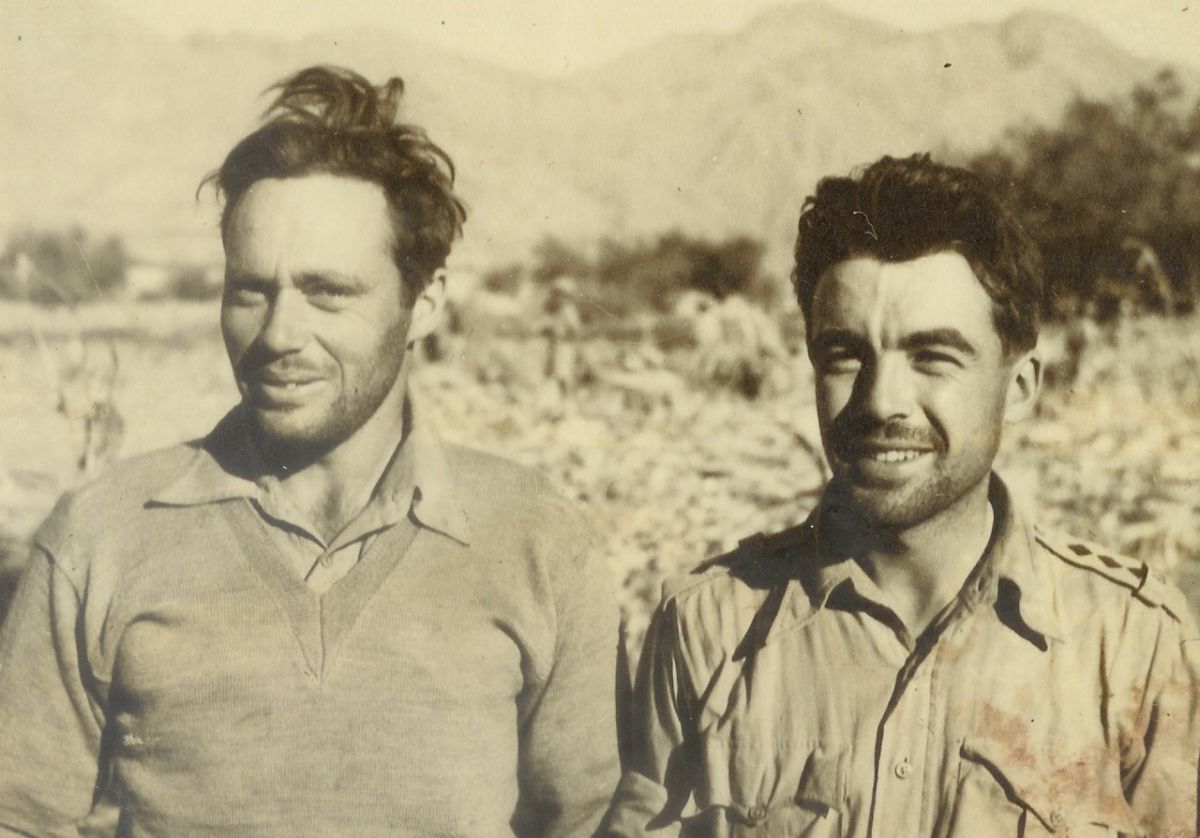

Photo above: Captain Vivian (on the right) shortly before the action detailed below.

Major Grahame Vivian MC*, who died in 2015, saw significant action in Burma for which he was awarded a Military Cross. Major Grahame Vivian entered the British Army in the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry but disappointed to be posted close to home. After volunteering for service with the Indian Army in December 1942 he joined the 4th battalion of the 8th Gurkha Rifles in India. His battalion deployed to Ranchi and to Arakan area of Burma towards the end of 1943.Military Cross Action

On 9th January 1944, then Captain Vivian was ordered to infiltrate Dhobi Hill which intelligence suggested was lightly defended. However, when he closed on the position he found it to be defended by the Japanese Army in strength. In spite of the enemy strength being greater than anticipated, he decided to attack. Once battle had been joined he was knocked over by a mortar shell and received wounds to his neck, chest, stomach and arm. He refused medical treatment and ordered his men to dig in and hold their position in the face of strengthening Japanese resistance. He continued to arrange the defence of the position until he was overcome by his wounds. Two of his men improvised a stretcher from their rifles and carried him for three days back to the regimental base His actions saw him awarded the Military Cross, the citation for which read: On the 9th January 1944, a company of this battalion was given the task of infiltrating on to Dhobie Hill in the Arakan. This company when it arrived near the objective found Dhobie Hill occupied by the enemy in some strength. Captain JEG Vivian, the company commander, immediately decided to attack. This officer was wounded by enemy mortar fire during the attack. Blown over by a mortar shell and painfully wounded in the chest, stomach and twice in the arm, he remained in command of his company. In spite of his wounds, he refused to be delayed by any medical attention and continued to command his company in the attack. In the meantime, the enemy had succeeded in reinforcing the position and infiltrating around our company. In spite of his wounds and in great pain, Captain Vivian still commanded his company and ordered his company to dig in and hold every inch of ground gained. In spite of his wounds this officer allotted defensive areas to his commands and continued to command and encourage his men until he himself was exhausted from the effects of his wounds. This officer’s conduct was a splendid example and an example of encouragement to his men. His actions throughout the operation were outstanding for resolution, leadership, conspicuous bravery and total disregard for his personal safety. Treatment and Recovery After the battle he was sent to military hospitals in Ranchi and Poona before being evacuated in 1945 to Princess Elizabeth Orthopaedic Hospital in Exeter. In Exeter he underwent several operations, especially on his right hand. For the rest of his life a piece of shrapnel remained in his shoulder and another in his throat (the removal of which was thought too dangerous). He was finally able to leave hospital in February 1946 when he rejoined the Gurkha Rifles at Quetta. He lead the Gurkha contingent in the VJ Day parade in London in 1946.

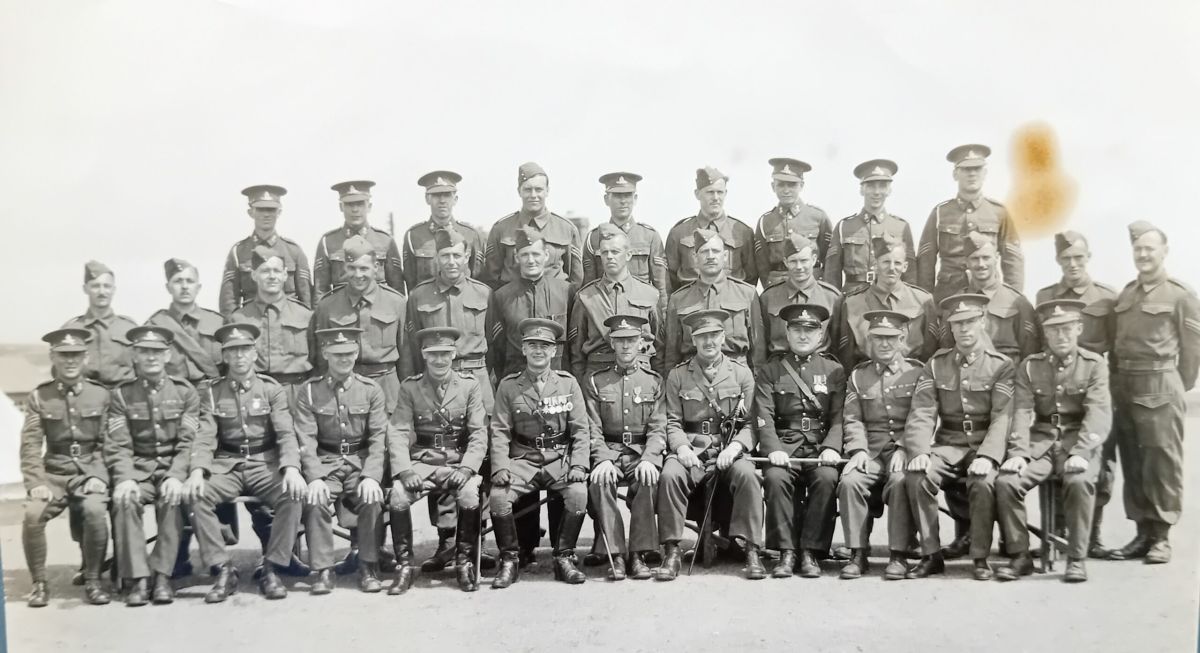

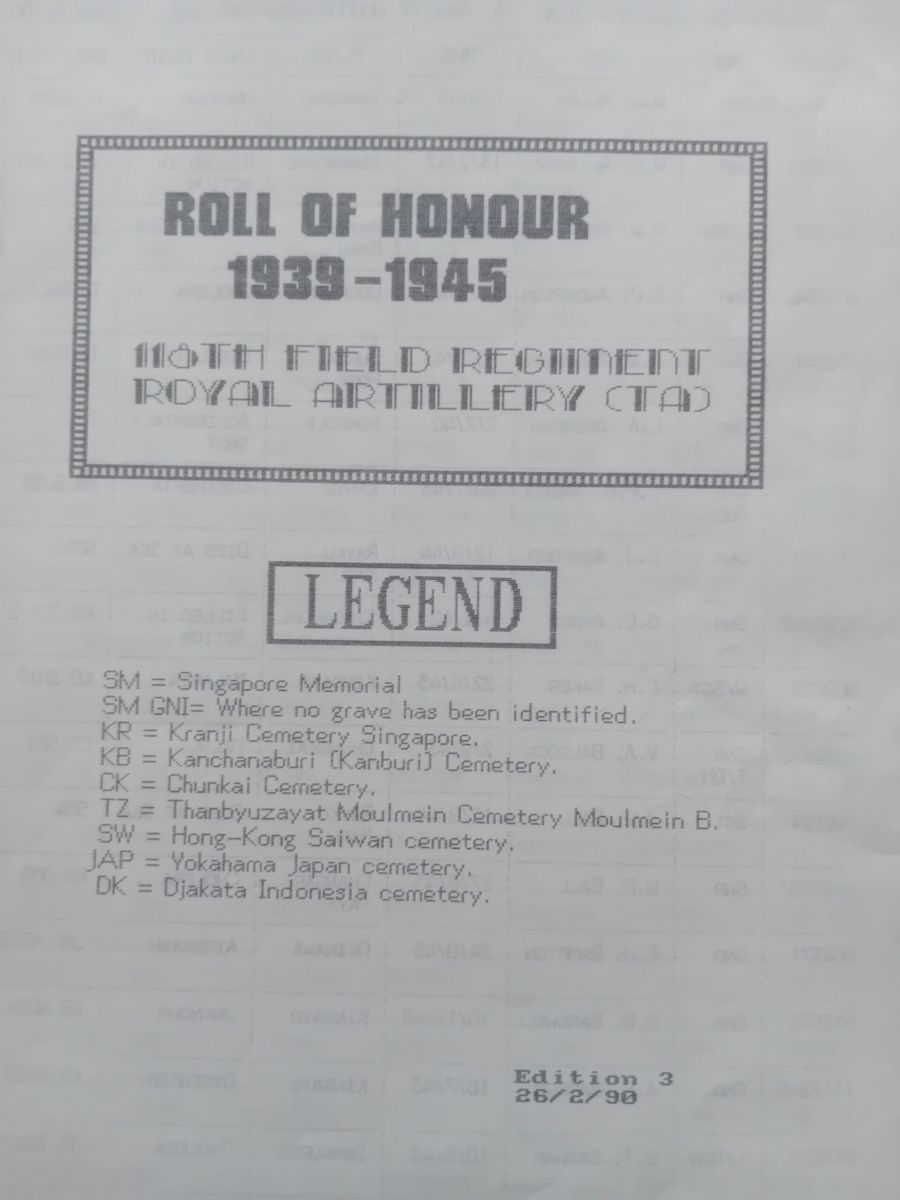

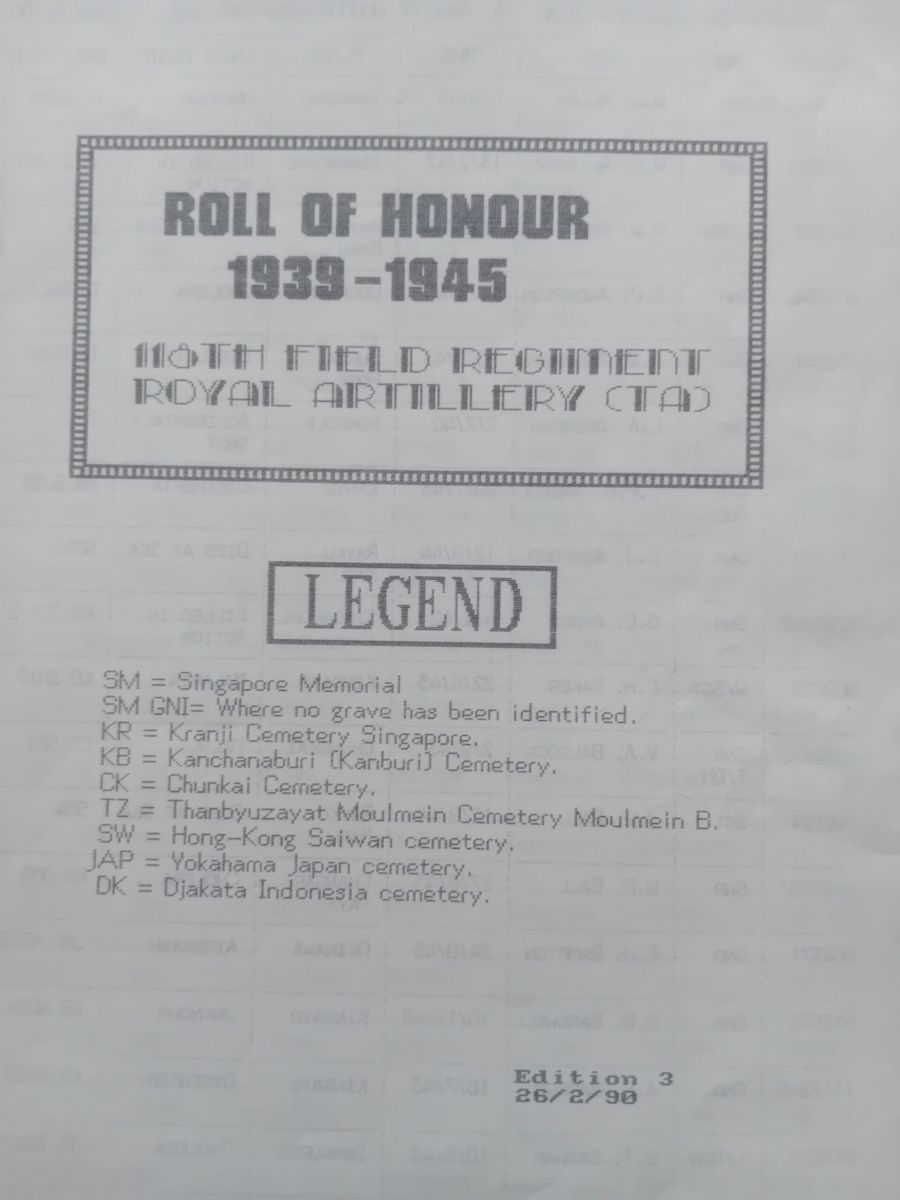

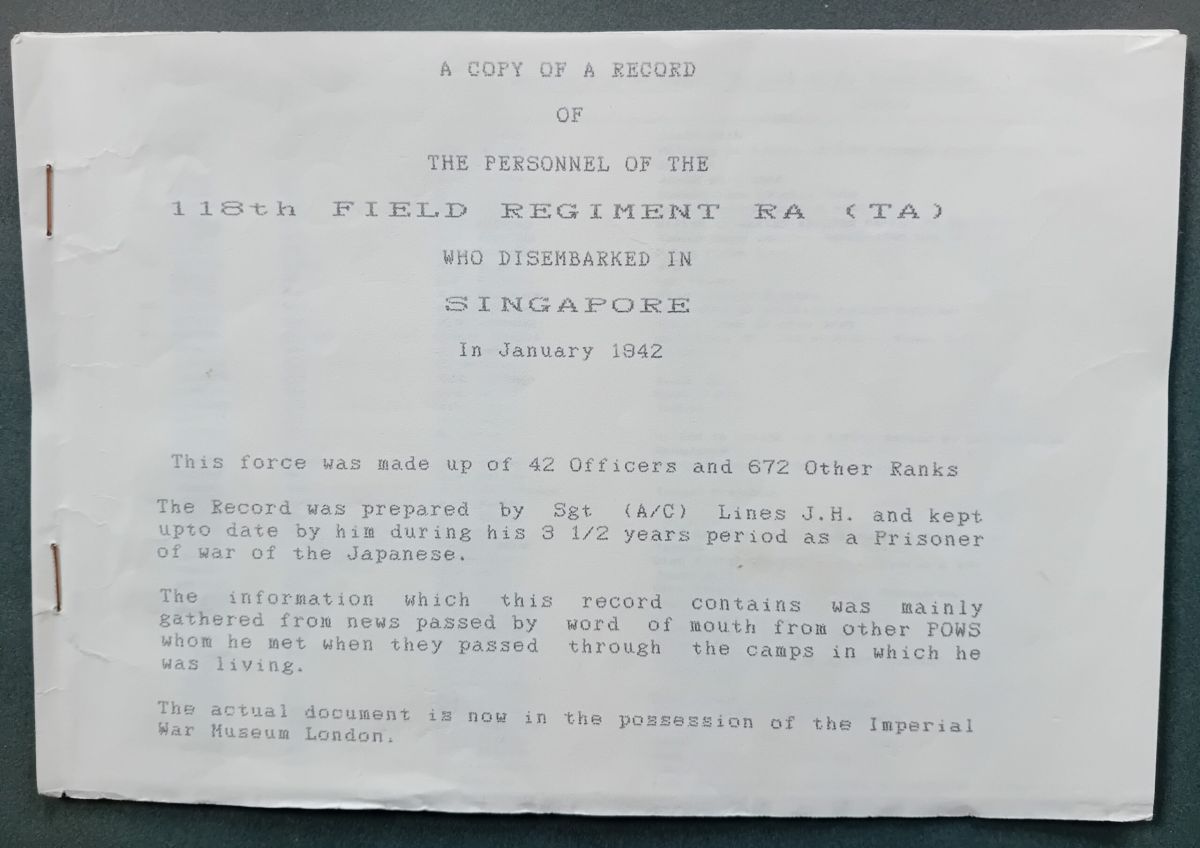

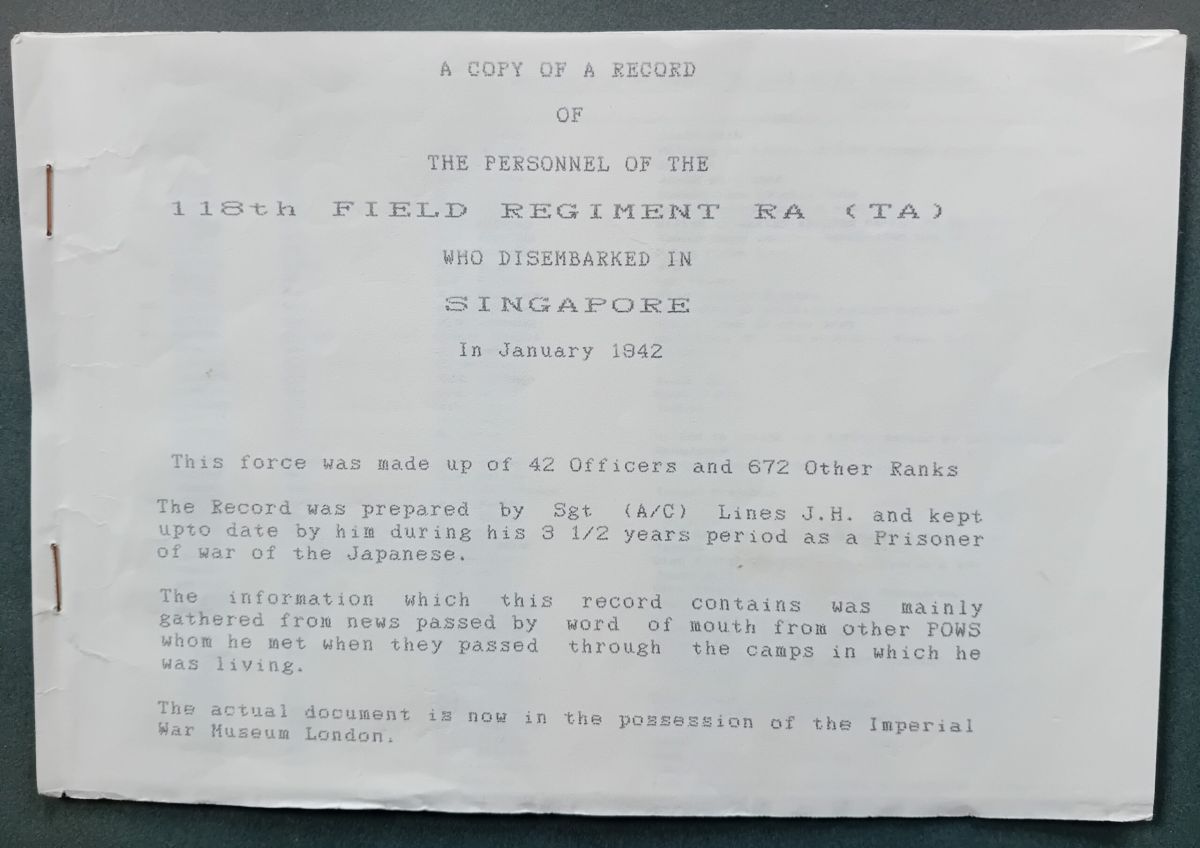

Bill Searle, 118th Field Regiment

Bill Searle, 118th Field Regiment

Submitted by Joan Barton regarding her the husband of her father’s cousin.

Bill Searle was a member of the 118th Field Regiment, which was deployed to the Far East shortly before the fall of Singapore in the Second World War. Bill had married into the family of VSC Member, Joan Barton, and was very much a part of her extended family as she grew up.

It wasn’t until later in life that the family came to understand the full extent of what Bill had endured during the war. Captured and imprisoned by Japanese forces, he was forced to work on the infamous Burma Railway under brutal and inhumane conditions. Bill never spoke about his wartime experiences—not to Joan or others in the family, apart from Jess—but his behaviour revealed much about the psychological toll it had taken.

Outwardly, he appeared lively, hard-working, and kind—the life and soul of any family gathering. Yet there were subtle signs of lasting trauma. At mealtimes, he would habitually overload his plate with food, only to leave much of it uneaten—perhaps a lingering response to the near-starvation he and his fellow prisoners endured. He would also avoid all conversation about Japan and would even go out of his way to avoid passing Japanese people in the street.

Bill was a close friend of Fergus Anckorn, a fellow soldier in the 118th Field Regiment and the longest-serving member of the Magic Circle. Fergus famously used his magic tricks to entertain the Japanese guards and, at times, to secure small extra portions of food—a quiet act of resistance and survival. Joan had the privilege of meeting Fergus on several occasions, the first being during the early days of the National Memorial Arboretum, when a memorial tree was planted in honour of those who served in the 118th. Sadly, by that time, Bill had already passed away. Joan reflects on Bill’s life with deep respect and gratitude, recognising the quiet strength and suffering of a man who, like so many others, carried the burden of war in silence.

Company Sergeant Major Robert Dawson Wright B.E.M., the Welch Regiment

Company Sergeant Major Robert Dawson Wright B.E.M., the Welch Regiment

Robert Dawson Wright B.E.M. served in the Welch Regiment during the Second World War. Known as Bob, he was born at Hunter Street off Sandy Row, Belfast.was a member of the 118th Field Regiment, which was deployed to the Far East shortly before the fall of Singapore in the Second World War.

His full story in the Northern Ireland archives can be viewed here: Robert Dawson Wright B.E.M.

Acting PO Walter Dudley Judd and Jack Pringle, HMNZS Gambia

Acting PO Walter Dudley Judd served as a gunner on HMNZS Gambia in the Pacific War and his son naturally has an interest in any news about that ship. As his son states:My father was very reticent to talk about it and in my naïve youth I unfortunately did not press him about it.”

The link below is the story of a New Zealand man Jack Pringle who served at the same time as my father on the Gambia prior to and during the VJ surrender. His story resonates word for word with my father’s limited account of his experiences at the same time.

In Tokyo Bay during the build up to the formal surrender my father skippered a Tender craft which was being used to ferry military officials from one ship to another, or to the shore. During one such voyage he was given a small Japanese Dress Sword by a Japanese Officer which I now have. I also have a framed certificate from the Admiralty declaring that HMNZS Gambia was the last ship to fire shells in anger at Japan at the Kamaishi steel works as described by Jack Pringle.

Jack Pringle’s recollections of war ending

Sadly, Jack Pringle passed away very recently as per his Obituary (link below).

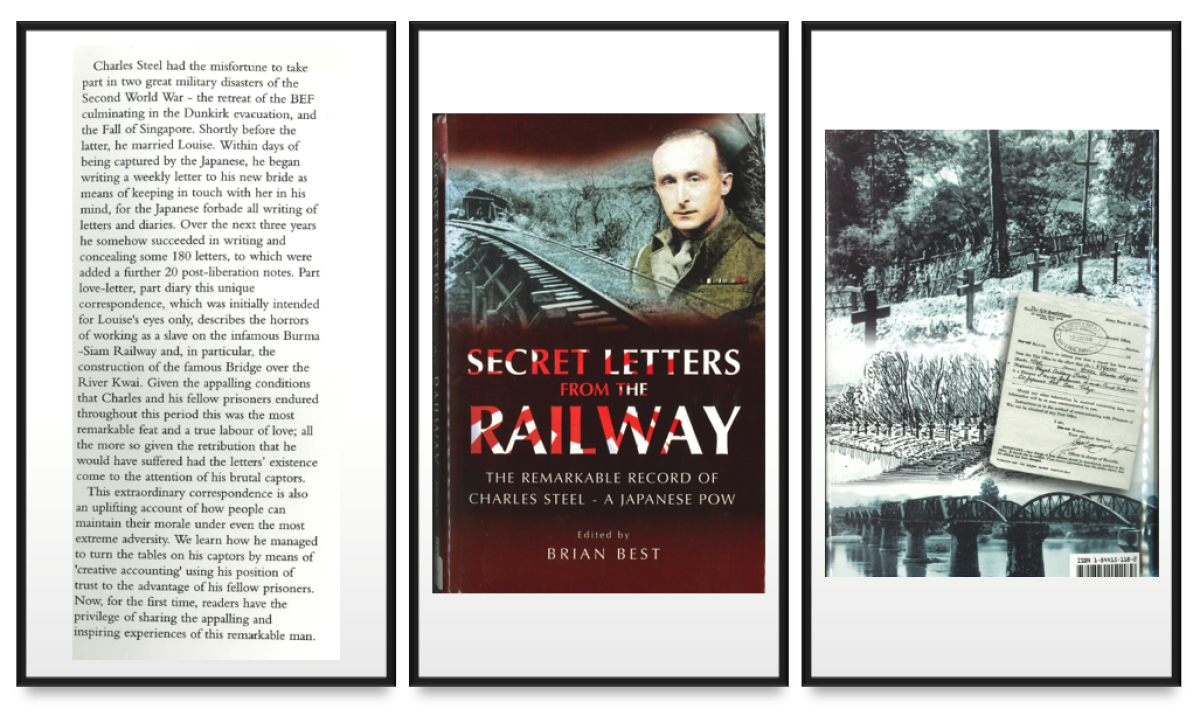

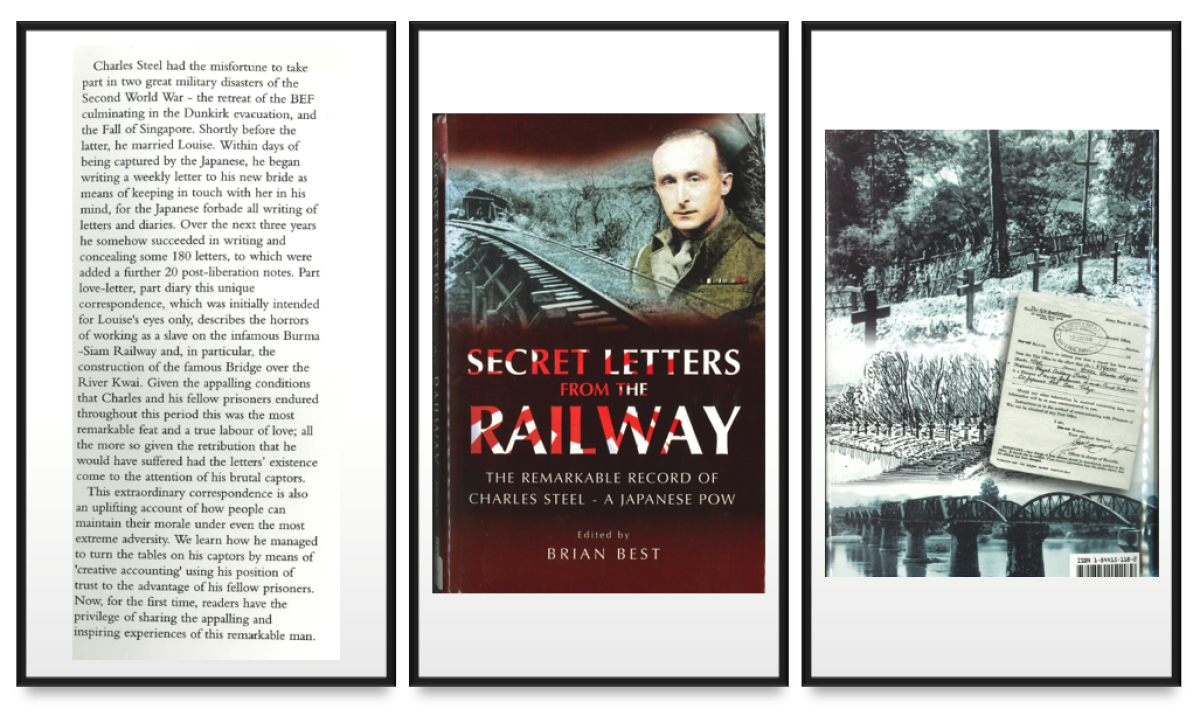

Charles Steel, 97 (Kent Yeomanry) Field Regiment Royal Artillery | A Japanese POW

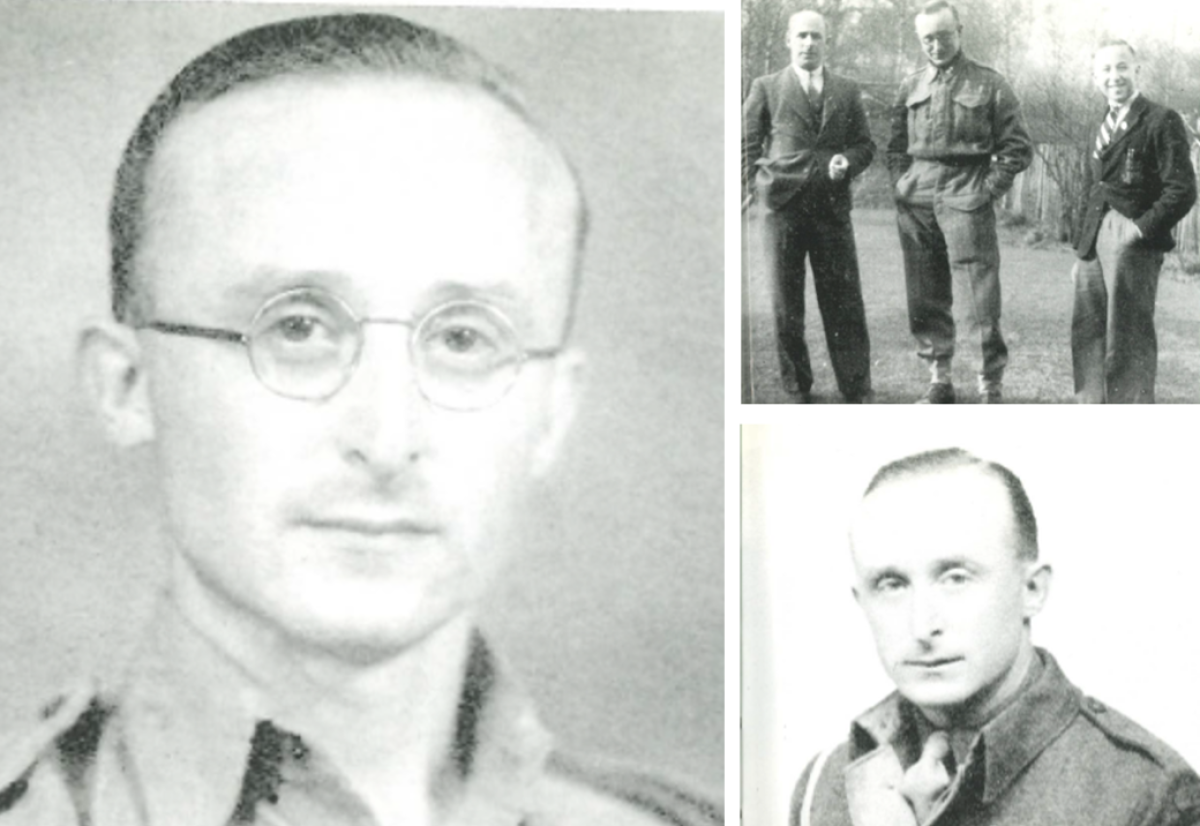

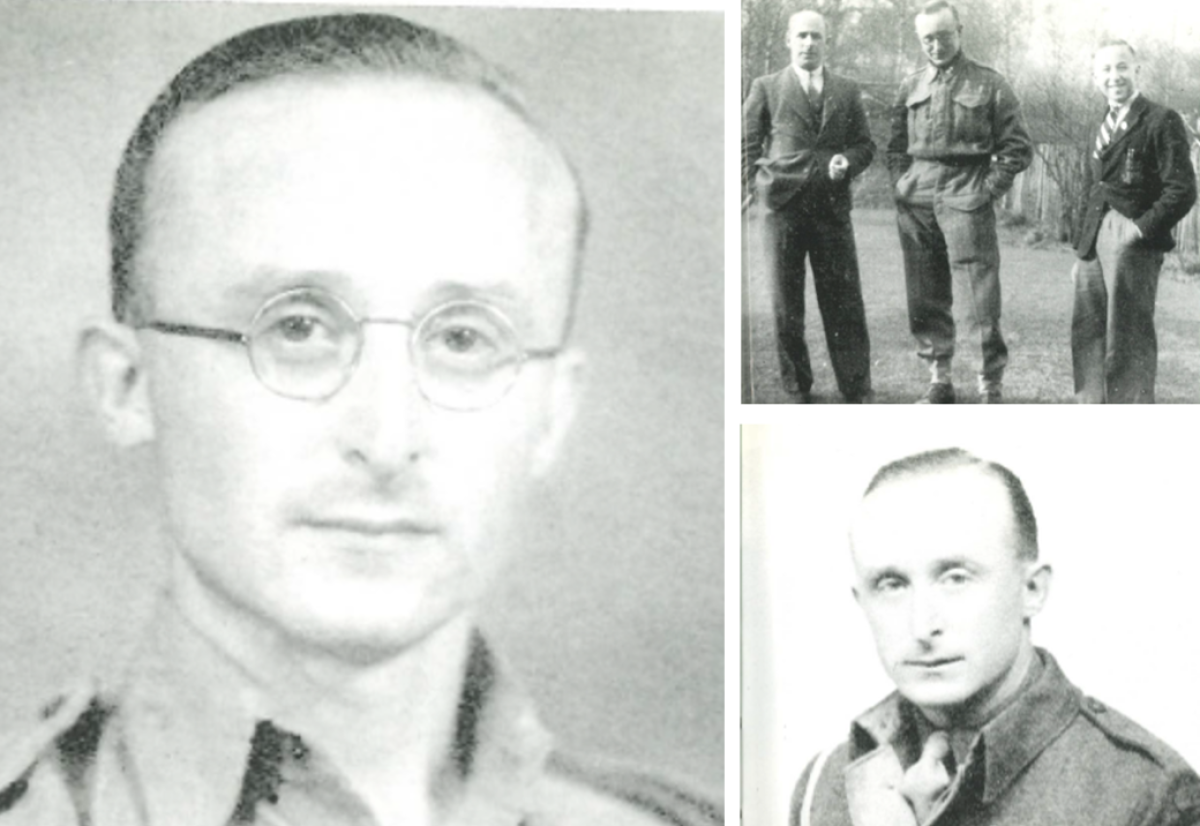

Photos above: Left: Charles in Mobasa, Kenya, December 1941 | Upper Right: Charles with his father and step-brother, Ken | WO2 Charles Steel 1945 | Submitted by his daughter, Margaret Sargent

My late father, Charles Steel, served with the 97th Field Regiment Royal Artillery, 387th Battery Queen’s Own West Kent Yeomanry at the outbreak of WW2. He transferred to the 336 Field Battery 135 (North Herts Yeomanry)Field Regiment after the fall of Dunkirk under the command of Colonel Toosey. A regiment “more distinguished socially than militarily.”

Following the Fall of Singapore in February 1942 and imprisonment in Changi my father realised his mind was as important as his body. He set himself the task of writing weekly letters to my mother (and ensuring their concealment) describing the horrors brutality and beauty, he encountered, in order to ‘be linked through the medium of pen and paper’. He vividly describes his part in building the Bridge over the River Kwai.

He was also involved in a scheme whereby the Japanese were swindled out of many thousands of pounds (in today’s money) by using ‘creative accounting’ for the canteen accounts – using the profits to buy medicine from the Thais.

In 2004 Pen & Sword published these letters in hardback, Secret Letters from the Railway and in paperback Burma Railway Man. Despite three and half years captivity, he had a very happy and fulfilling life, returning to work on the London Stock Exchange. Strangely he always loved railways and indeed learnt to drive a steam engine aged 73!

Some of the images from the Secret Letters from the Railway – A Remarkable Record of Charles Steel – A Japanese POW

-

Charles and his BEF comrades in Northern France, 1939 -

135th (Herts. Yeomanry) Field Regiment RA, 336th Battery -

Attap huts, Malaya -

Map of Singapore Island -

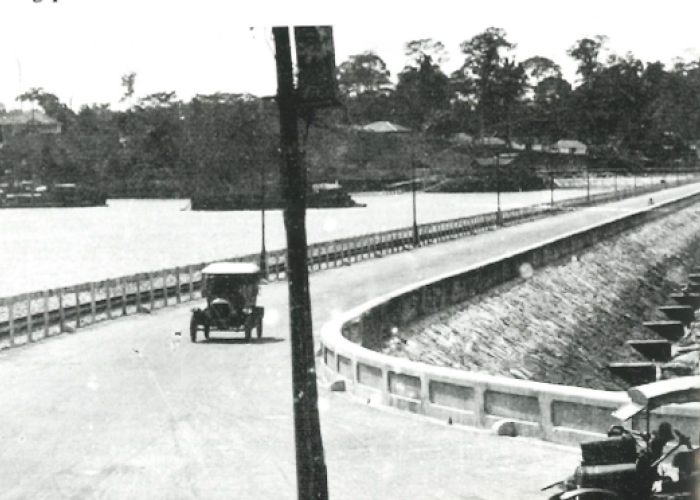

Singapore: the causeway across the Johore Strait -

Singapore river barges -

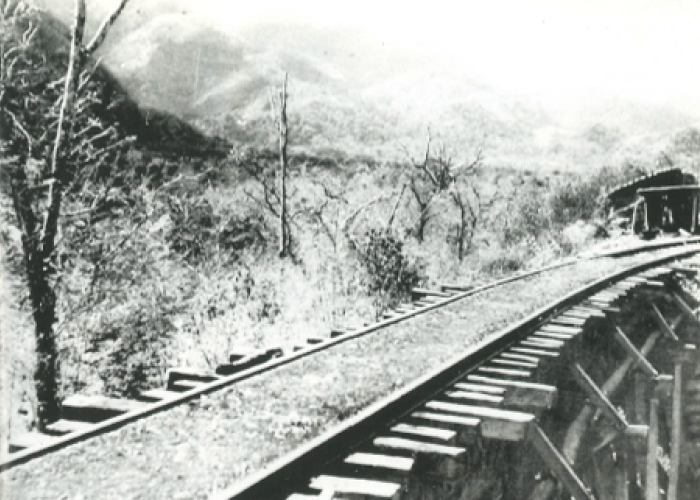

Completed railway, near Kinsiok -

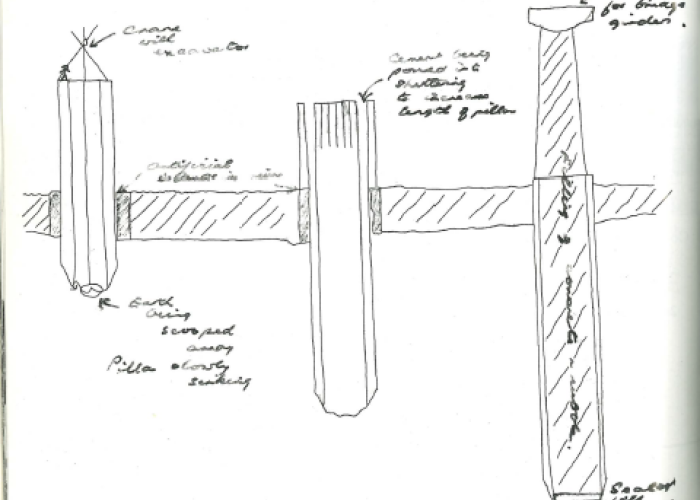

Drawings of the bridge piling -

One of the many trackside cemeteries -

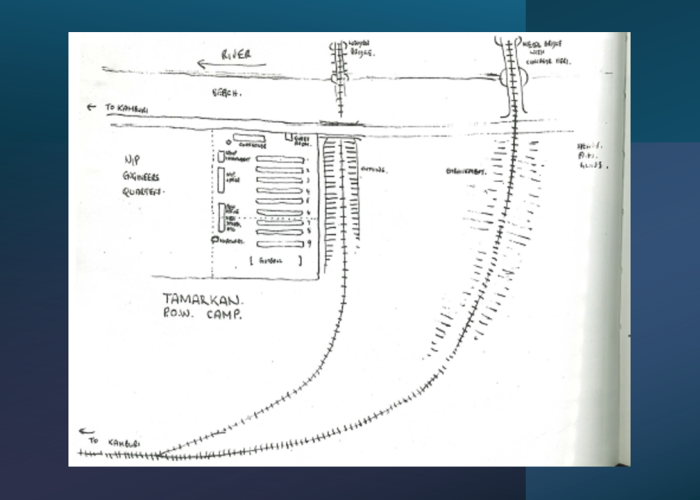

Layout sketch of Tamarkan POW cam and location of two railway bridges -

Lord Louis Mountbatten in Singapore at the end of the war -

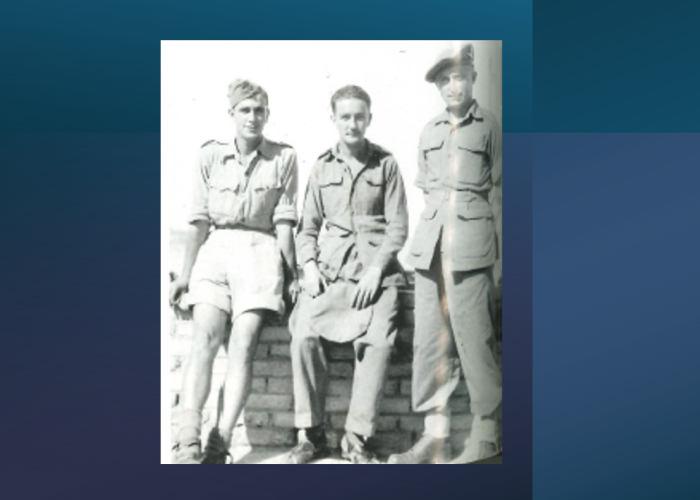

On the way home. Left to right: Sergeants Parsons and Edwards, with Charles Steel in Suez, Egypt -

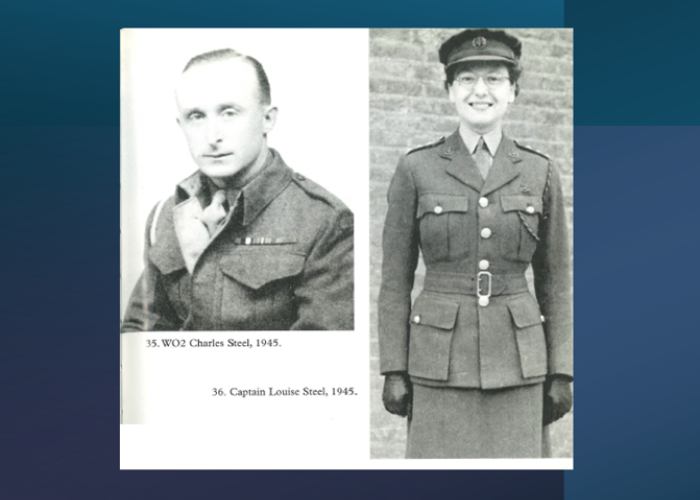

WO2 Charles Steel, 1945 | Captain Louise Steel (wife), 1945 -

Charles visits the bridge, 1973 -

Louise by the bridge, 1973

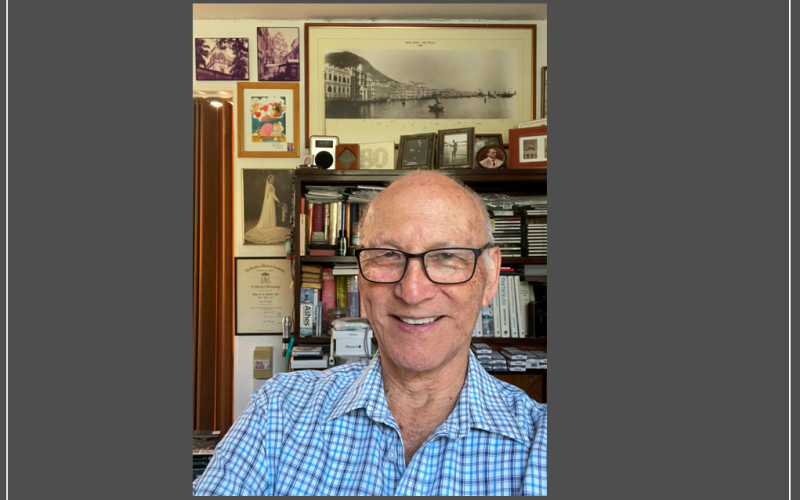

Peter Hall, Childhood POW, Stanley Internment Camp, Hong Kong

Photo above: Peter Hall, on far left hand side waving | His sister, Sheila, is in the 3rd row, with her hand across her face.

Peter Hall, son of George Albert Victor Hall, Sergeant, Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDV) , recounts the memories of the time where his entire family was taken as POWs by the Japanese. Some are extracts from his father’s diary and a few from Peter’s own recollection.

Members of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps

The Hall Family Story

It all began on Monday, 8th December 1941, when George Hall heard on the radio that Japan had declared war on both the United States and Great Britain.

Within an hour, the entire family had packed their belongings and were ready to leave. Just as they were heading to the Kowloon–Canton Railway Station, several planes flew overhead, dropping leaflets. George had been granted leave to escort his family back to Hong Kong, but their efforts were in vain. A travel permit from the YMCA was required, and enormous queues had already formed in front of the ferries.

Mabel Hall — Peter’s mother and George’s wife — called her boss, who had offered to take their family (Peter, his older brother Michael, and younger sister Sheila) to Hong Kong. George was instantly requisitioned as a Captain’s orderly. The next time Mabel and George spoke was a week later — and it turned out to be their last contact.

-

George Hall (1897-1956) | Mabel Gittins (1904-1985) Taken in 1923. -

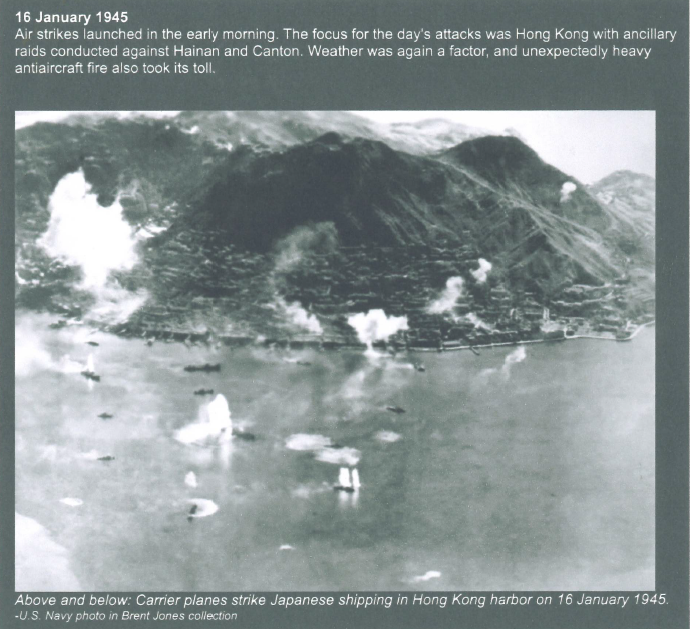

Carrier planes strike Japanese shipping in Hong Kong harbour on 16th January 1945 -

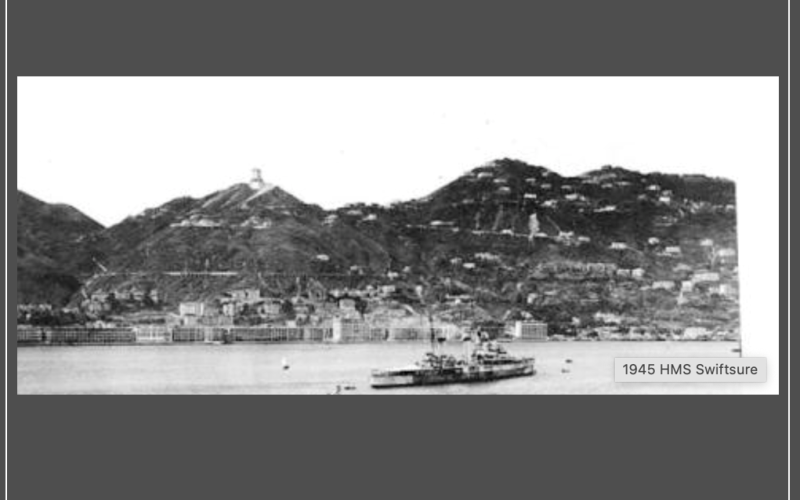

HMS Swiftshire in HK harbour with the huge Japanese Memorial on Mt Cameron, completed on 8th December 1943 (exactly two years after the Japanese attacked HK) and demolished on 26th February 1947. It contained the ashes of all the Japanese who died in the Battle for Hong Kong. -

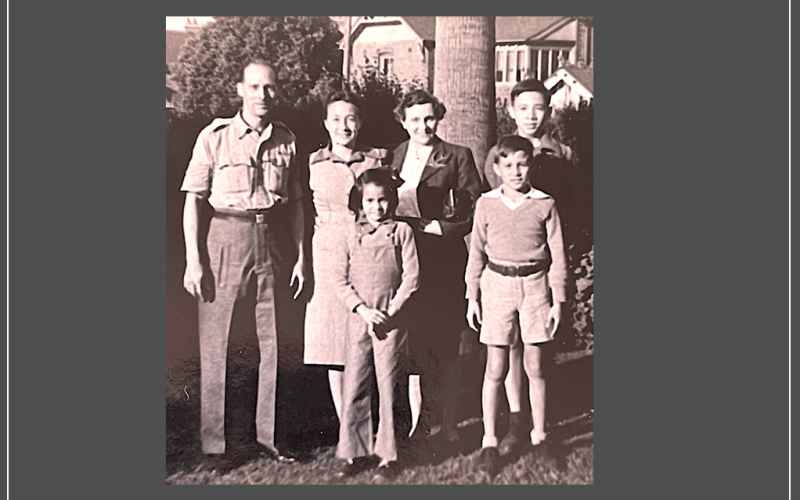

Sydney 1945 | George (in army uniform), Mabel, Phyllis Capell (a bridesmaid), Michael, Sheila & Peter -

George & Mabel’s 25th Anniversary Year | Beach House 1954 | George, Mabel, Peter, Sheila & Michael -

Peter in his home office, with a photo of the Praya, Hong Kong in 1889. Peter was Company Secretary of The Hongkong Land Co., Ltd. from 1970-1990. The photo was presented on Hongkong Land’s 100th anniversary in 1989.

Photo above: Information on Stanley Internment Camp January 1942-December 1945

After that, George had no knowledge of Mabel and the children’s whereabouts until 1st February 1942. By then, he was interned at the Sham Shui Po Military POW Camp, where he received a food parcel from his sister containing a note.

“Mabel and children are all well at Stanley. Children have milk. Love Ruby.”

In the meantime, Peter and his family moved whenever the Japanese got too close to them, until 5th January 1942, when they were informed “all enemy subjects” would be interned, finally after a rough count, everyone was marched off west.

“The Japanese were determined to humiliate the foreign imperialists”, as they chose Stanley as their next accommodation. Stanley as described in a post war book “Stanley behind barbed wire”, “was part brothel and part boarding-house in the poorest section of the town which in normal times catered for impoverished seaman. The accommodation offered was filthy and verminous, kitchen and sanitation facilities were deplorable – there was no water even for toilets – and hardly any natural light ever penetrated dirty windows set high up at the end of long narrow corridors.”

Before the family knew they were headed off to Stanley, Peter became sick with jaundice and had to be left behind, while his mother Mabel, brother and sister had departed for Stanley. Peter remembers his mother telling him many years later, that at the time, she thought she would never see him again.

What a Bombshell | 8th December 1941

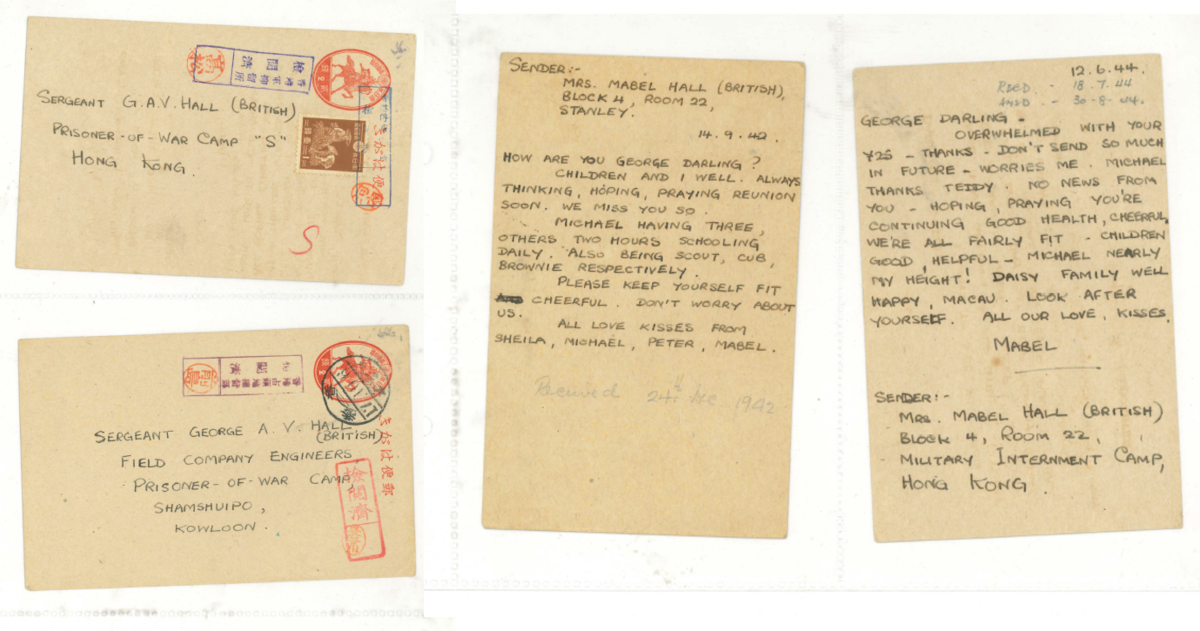

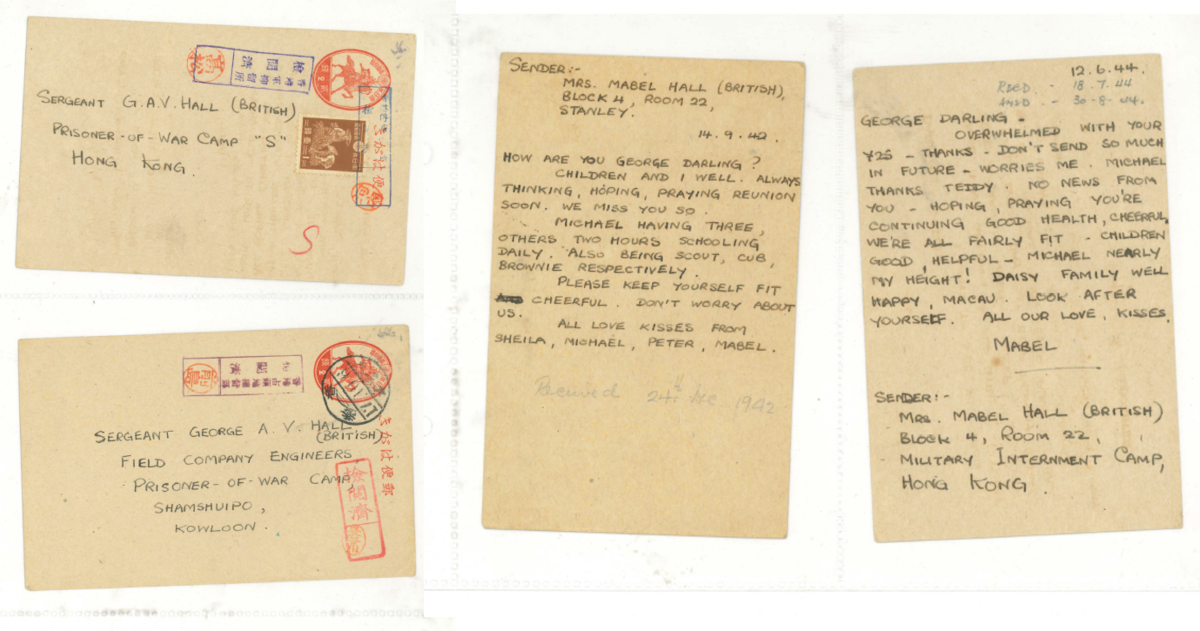

When they left Bellemere on 8th December1941, Peter never imagined it would be years before he returned — not until 17th September 1945. During the war, his father, George A. V. Hall, was interned at the Sham Shui Po Military Camp in Kowloon, while Peter, along with his mother, brother, and sister, was held at the Civilian Internment Camp in Stanley, at the southern end of Hong Kong Island. Mabel wrote to George, not knowing if he received her letters.

Letters from Mabel to George

The family finally reunited on 20th August 1945, and George recalls,

“Mabel a little older, Michael the same height as Mabel, 1st in class. Peter full of life and Sheila non-stop talker, seedy-all grown.”

Looking back on the events from December 1941 to August 1945, Peter considers himself fortunate not to remember “all the really bad times during that violent, stressful period.”

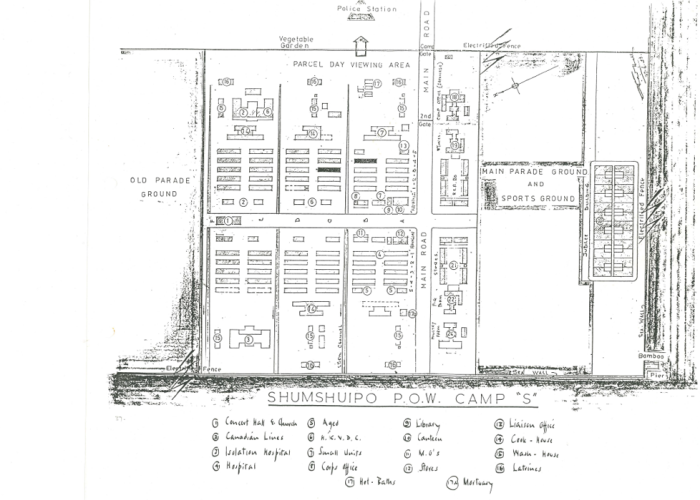

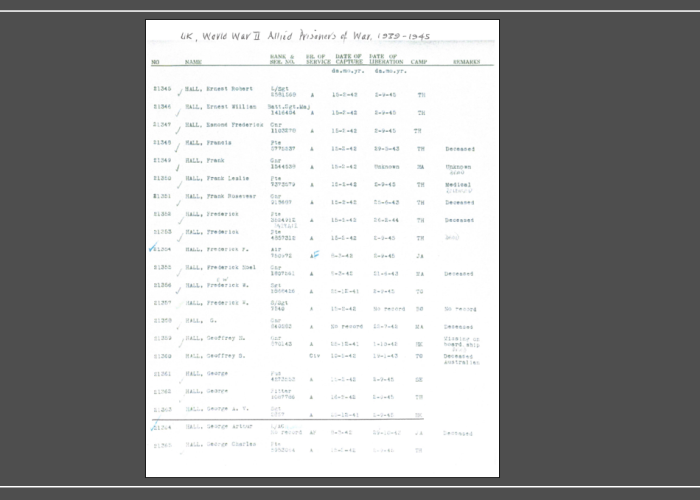

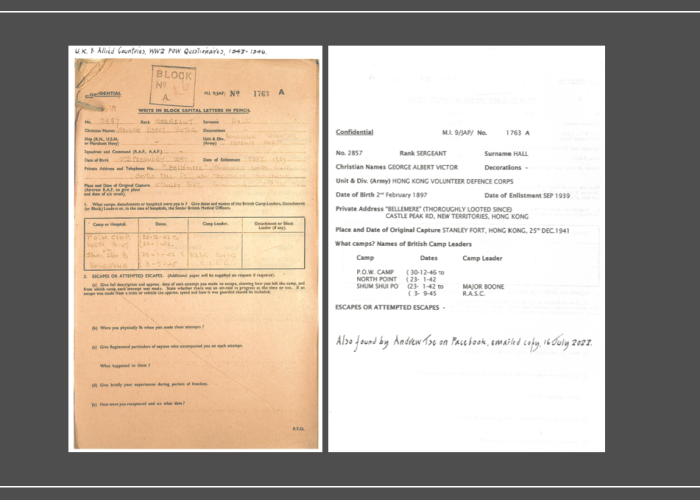

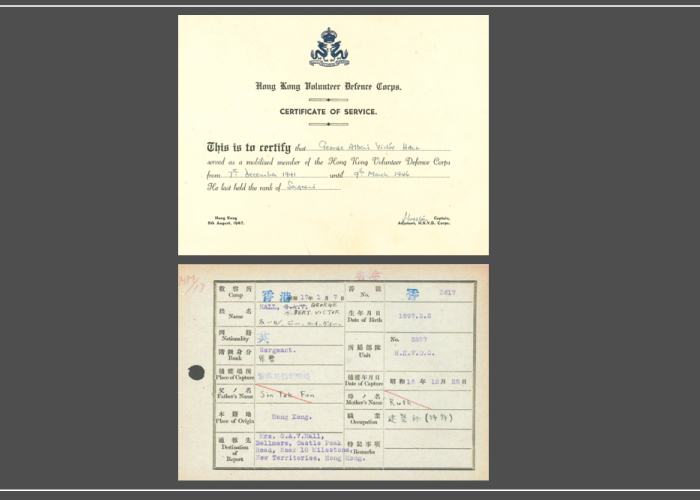

Sham Shui Po Camp POW & Hall, George A.V. Military Records

-

Map of Sham Shui Po Camp by George AV Hall -

Sham Shui Po Camp POW record for ‘Hall’ surname

-

George AV Hall’s POW Questionnaire -

George AV Hall – Medals -

George AV Hall’s Certificate of Service

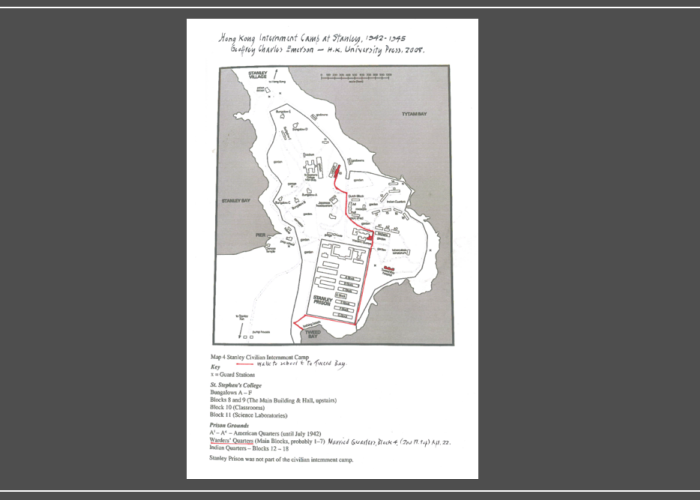

Stanley Internment Camp January 1941-December 1945

Information on Stanley Internment Camp January 1942-December 1945

Hong Kong Civilian Internees – Official List Stanley Civilian Internees – by Category and Age-

Map of Hong Kong Civilian Internment Camp at Stanley -

List of POW children under 16 -

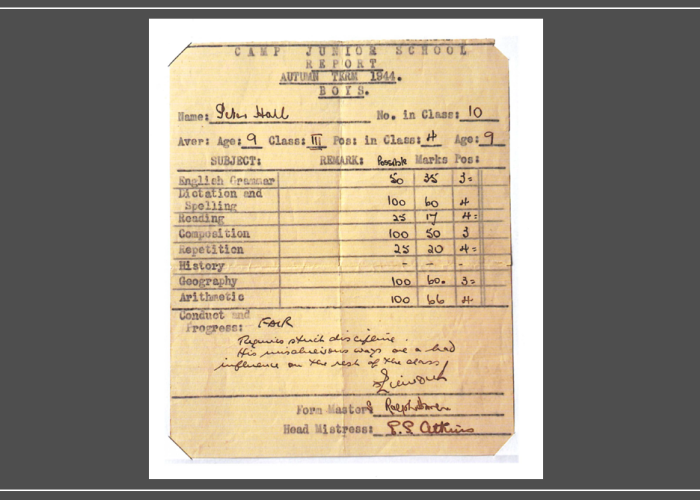

1944 Stanley Camp School Report – Peter Hall -

Repatriation List 1943 (partial) -

Cap badges found by Peter Hall while a POW -

Hong Kong POW Association Wall Badge -

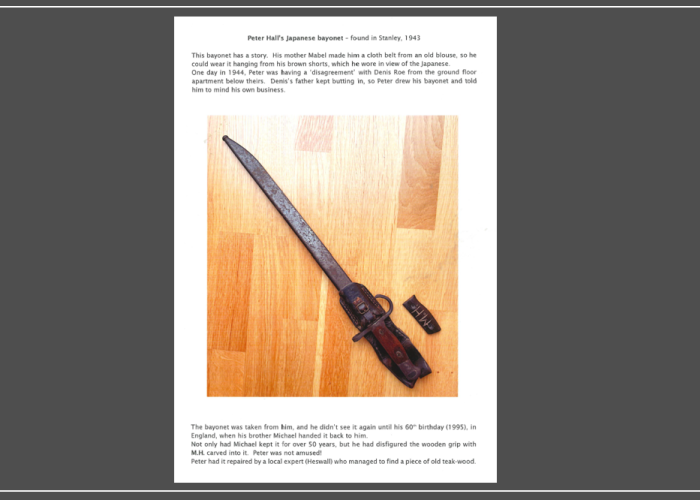

Peter Hall’s Japanese Bayonet

Japan’s WWII Intentions Toward Allied POWs

The Japanese Surrender | 15th August 1945

Peter Hall’s Campaign on behalf of Hong Kong Internees

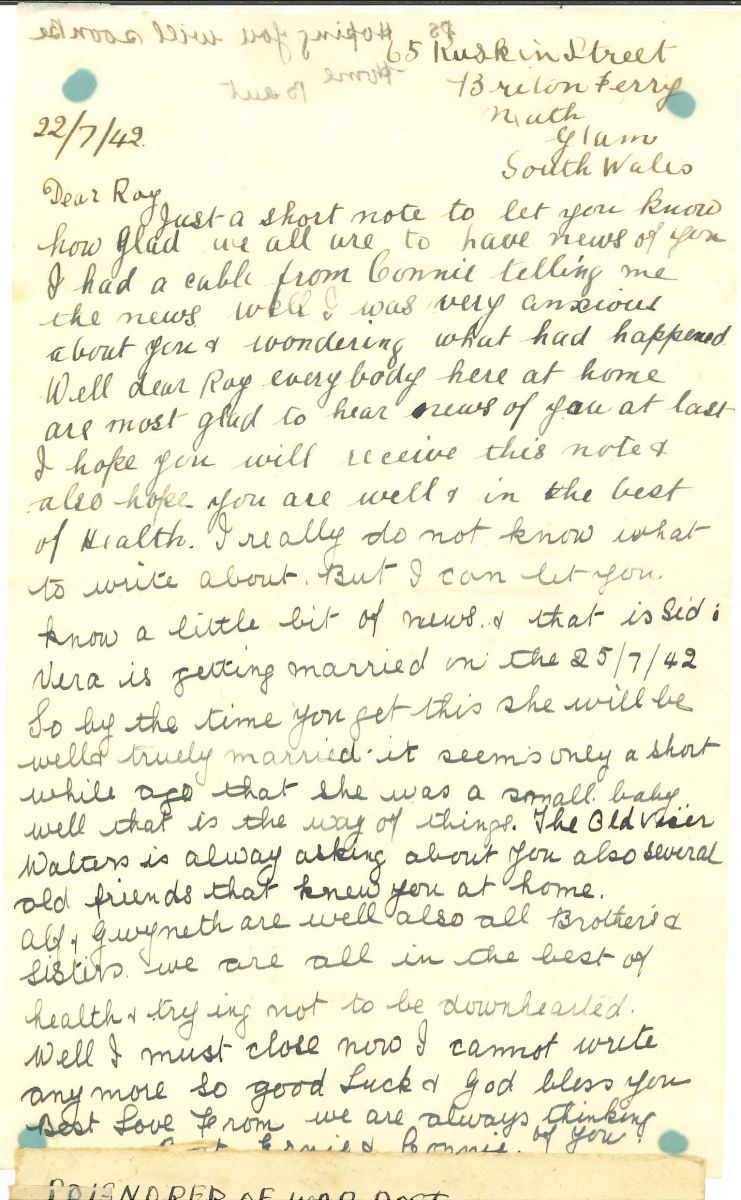

Robert Sidney Rosen (Roy), South Wales Borderers & POW

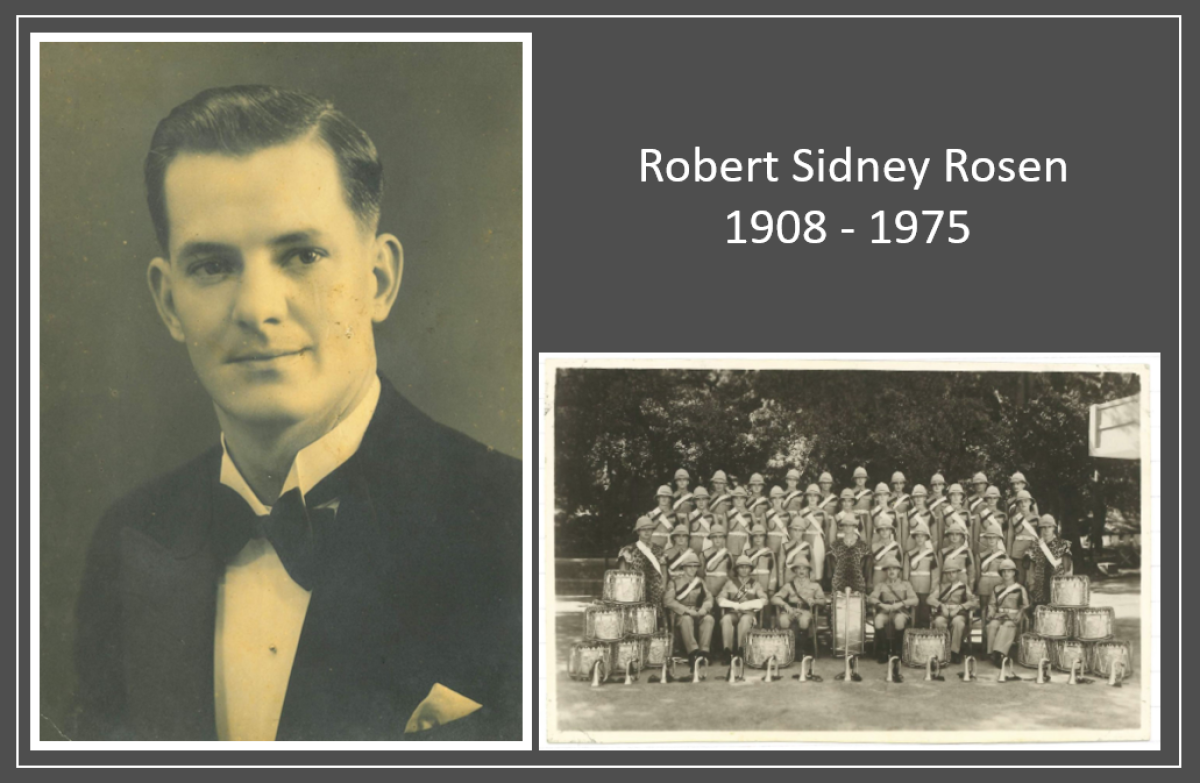

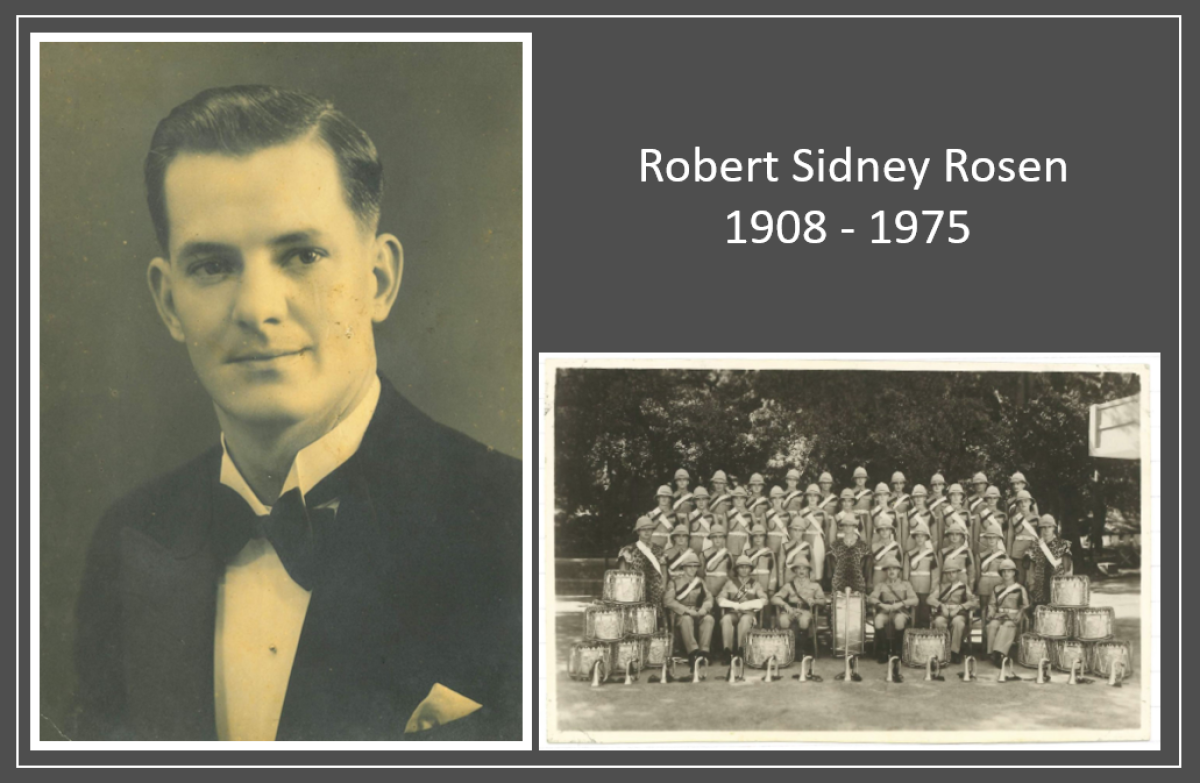

Photos above: Robert ‘Roy’ Sidney Rosen serving with his regiment. In 1928, the regiment sailed for Hong Kong, from where he later had the opportunity to visit Canton in China, playing the trumpet in the army band. Very little is known about his army life in Hong Kong. Much of this content formed part of a school project by his grandaughter.

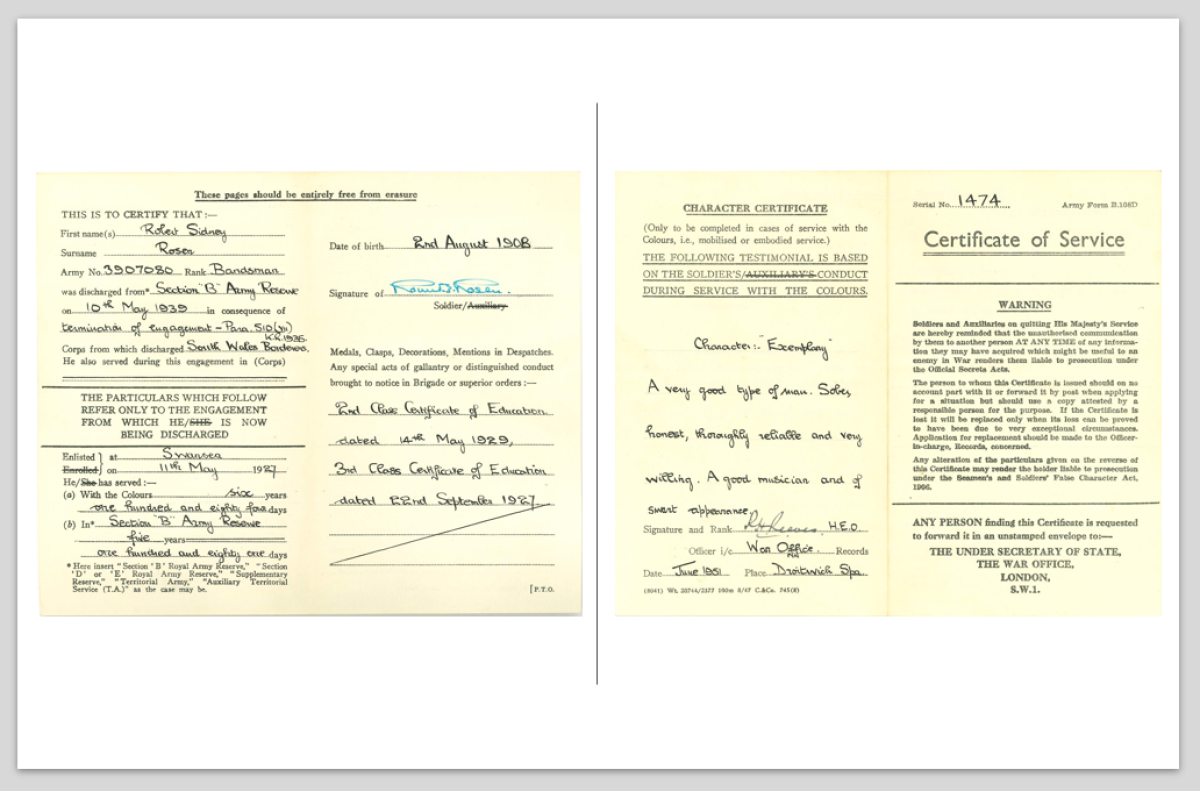

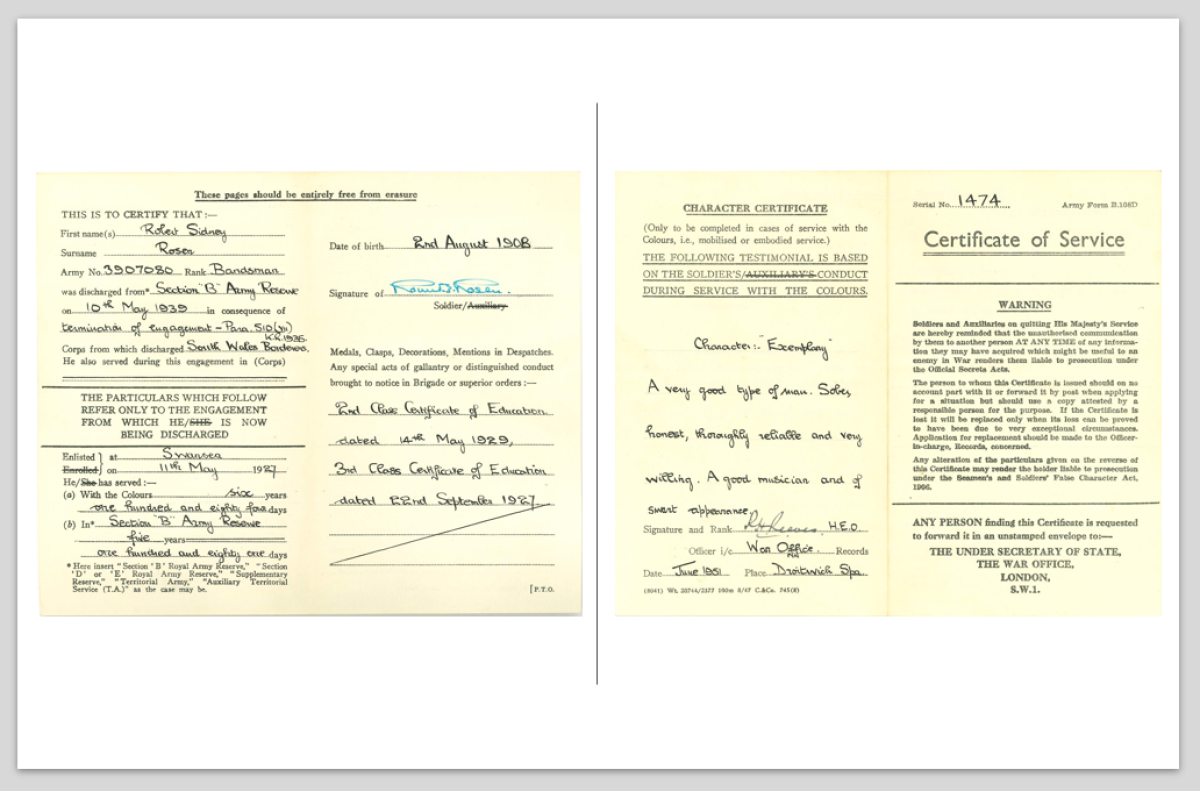

Army Discharge Papers

Capture & Life as a POW | ‘Roy’ Rosen’s Hong Kong Story

Stanley Internment Camp, Hong Kong

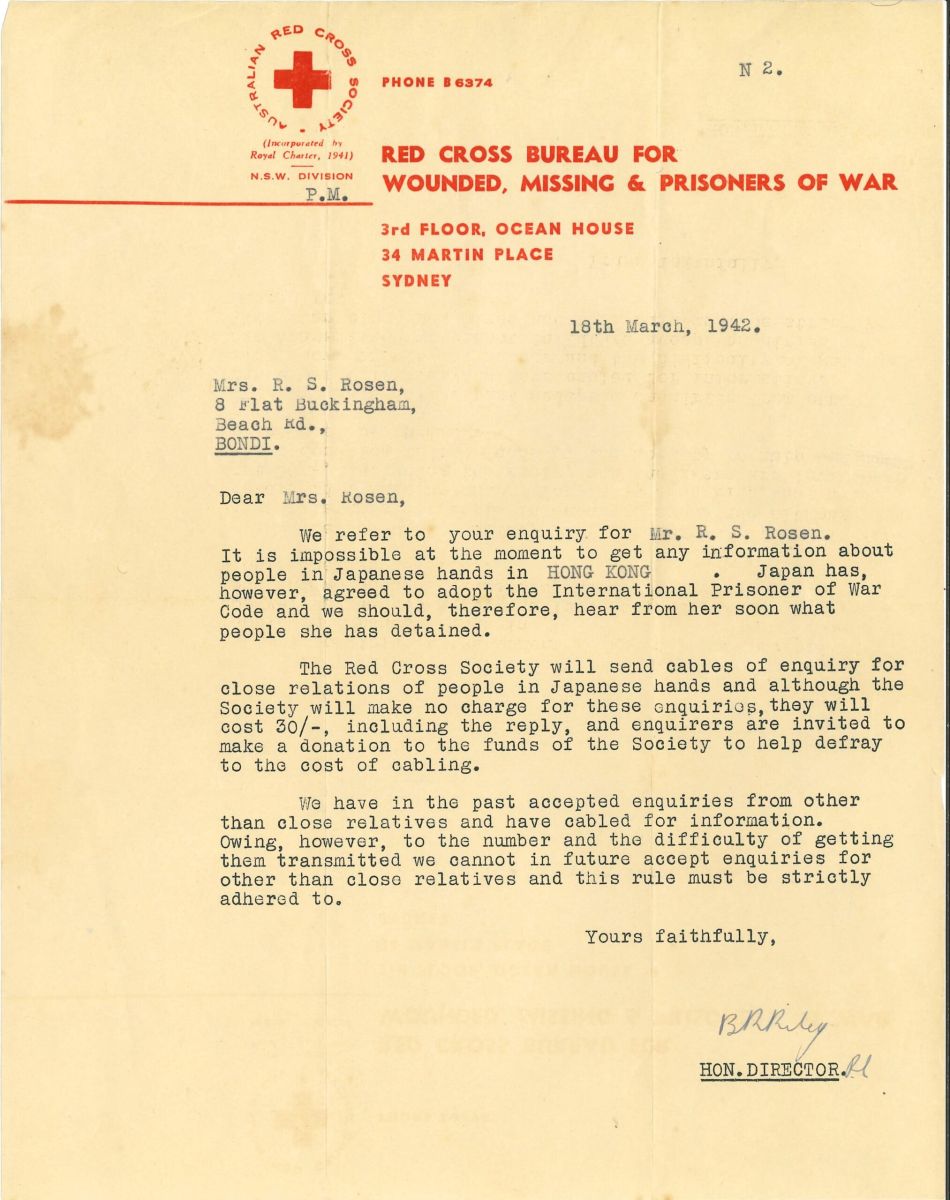

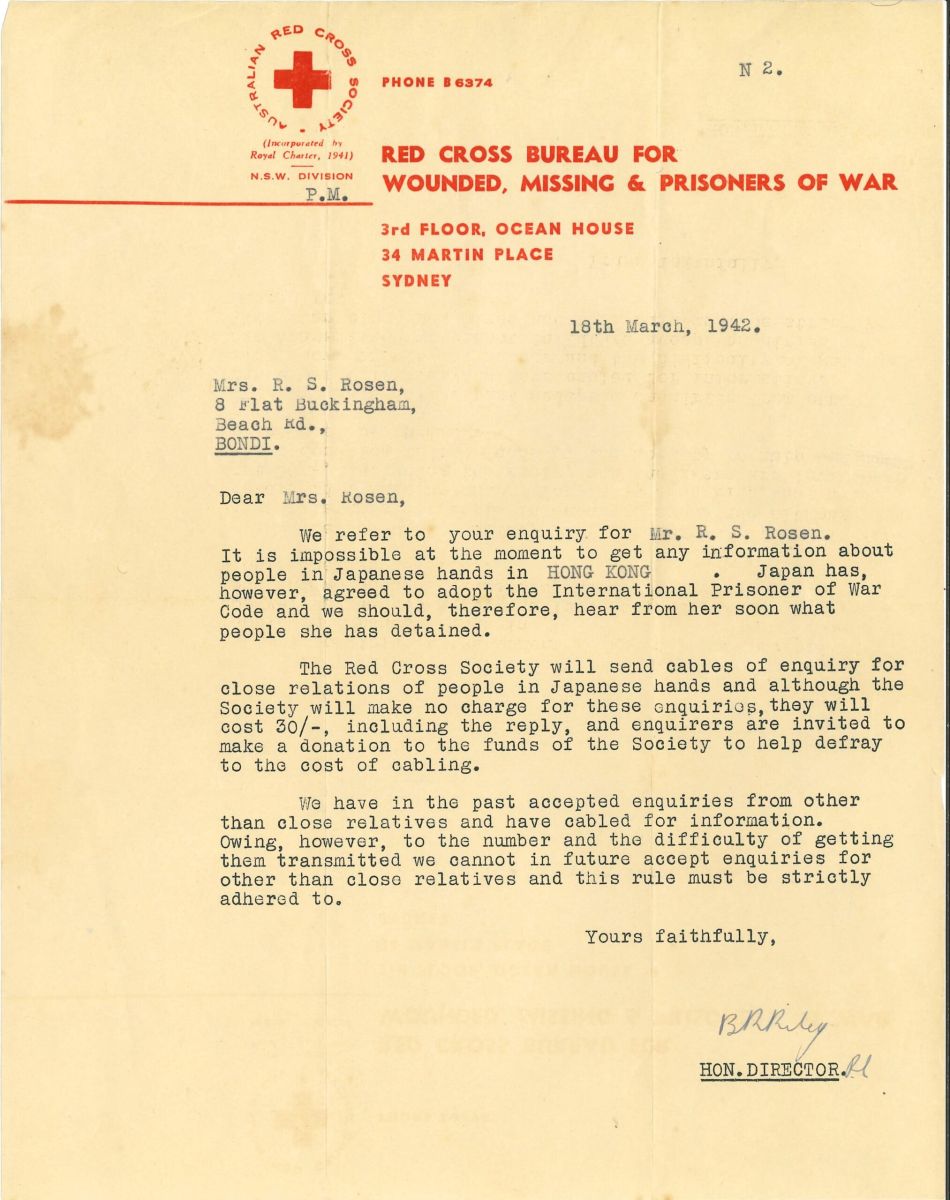

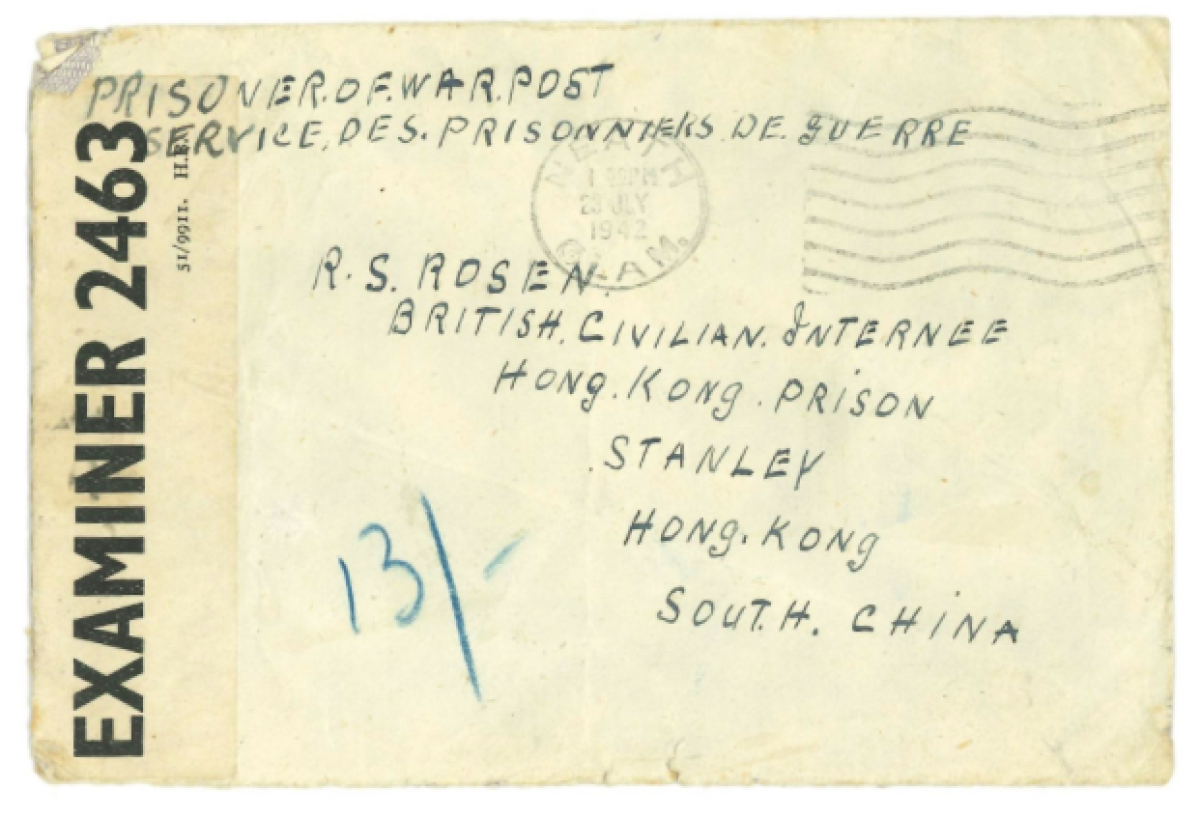

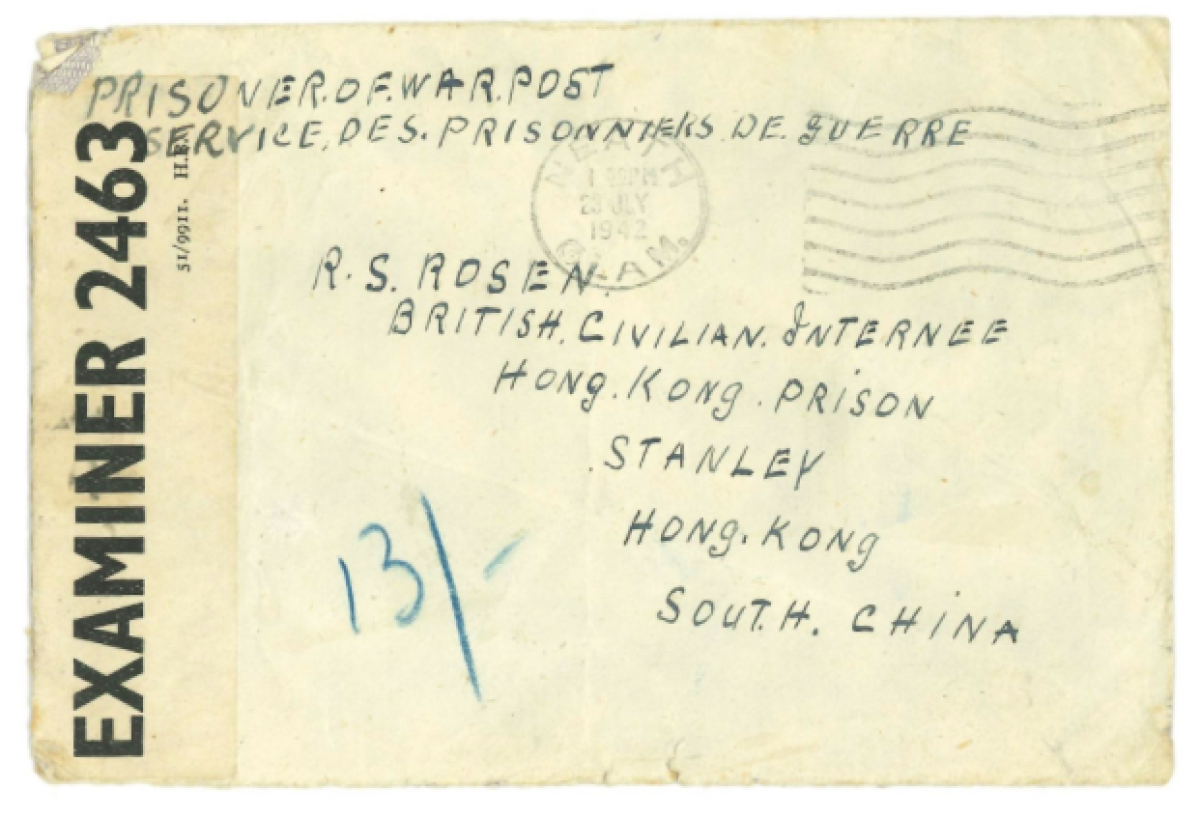

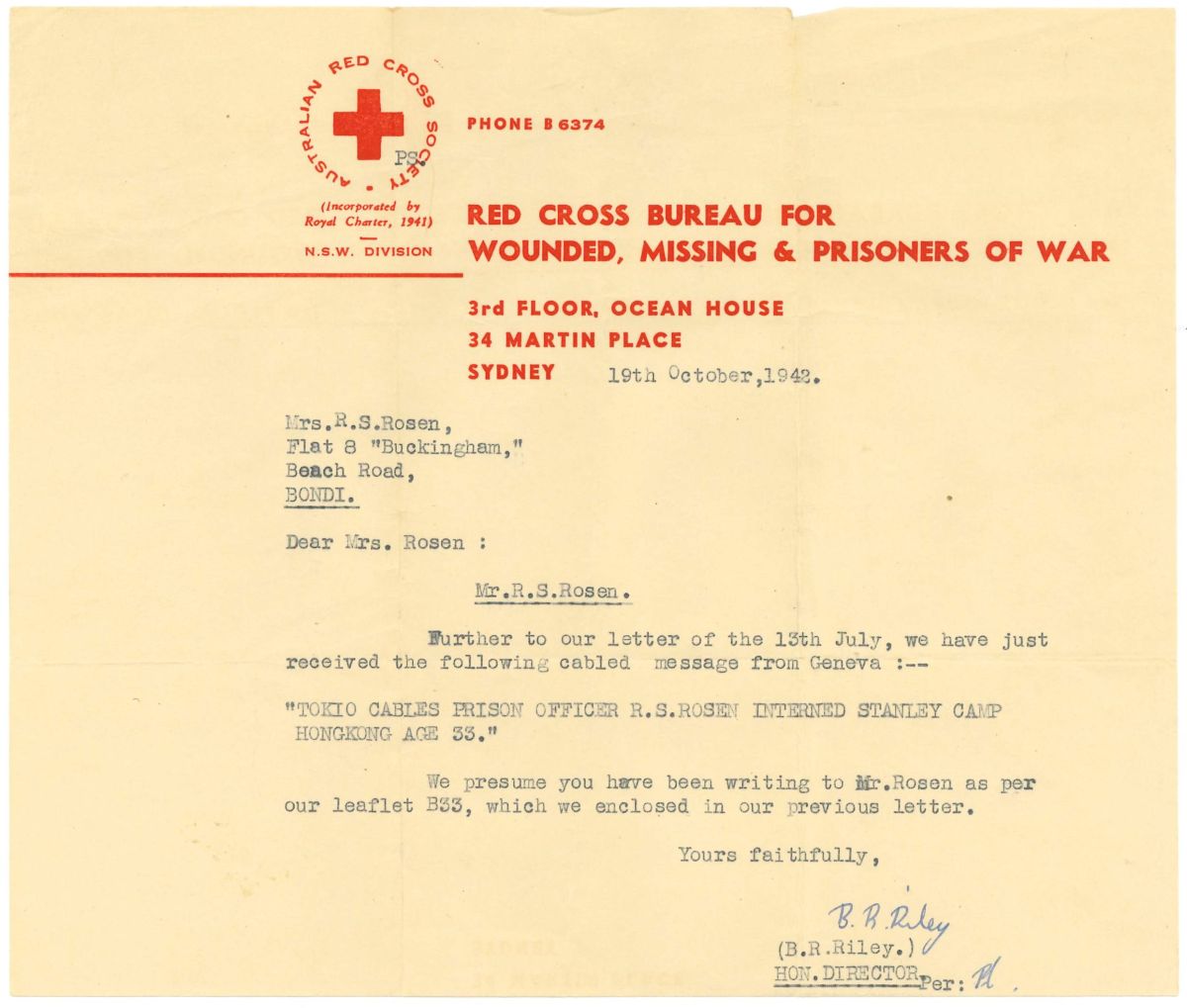

RED CROSS LETTERS | Sent to Roy’s wife, confirming where he was being held.

Telegram | 19th March 1942

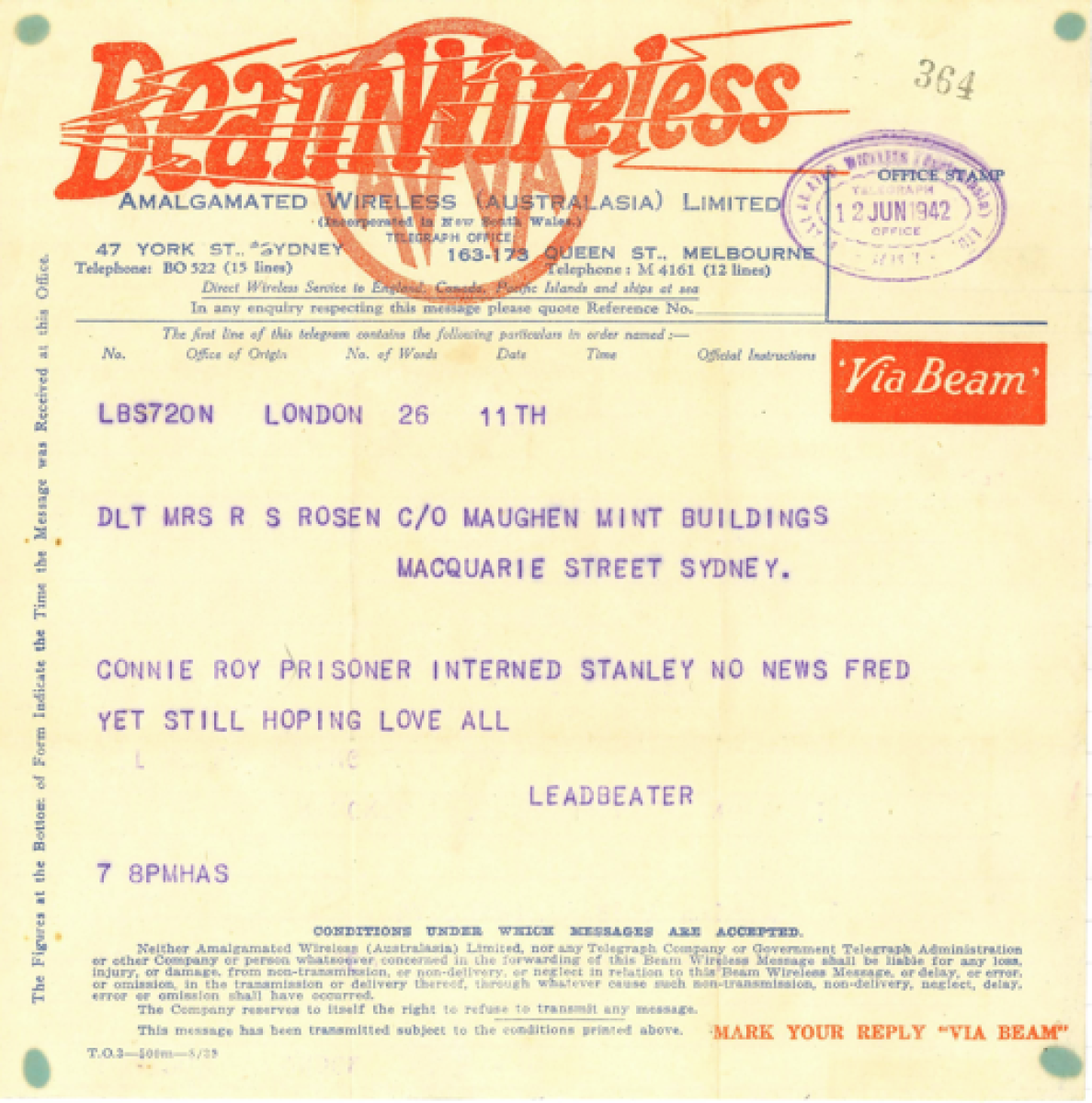

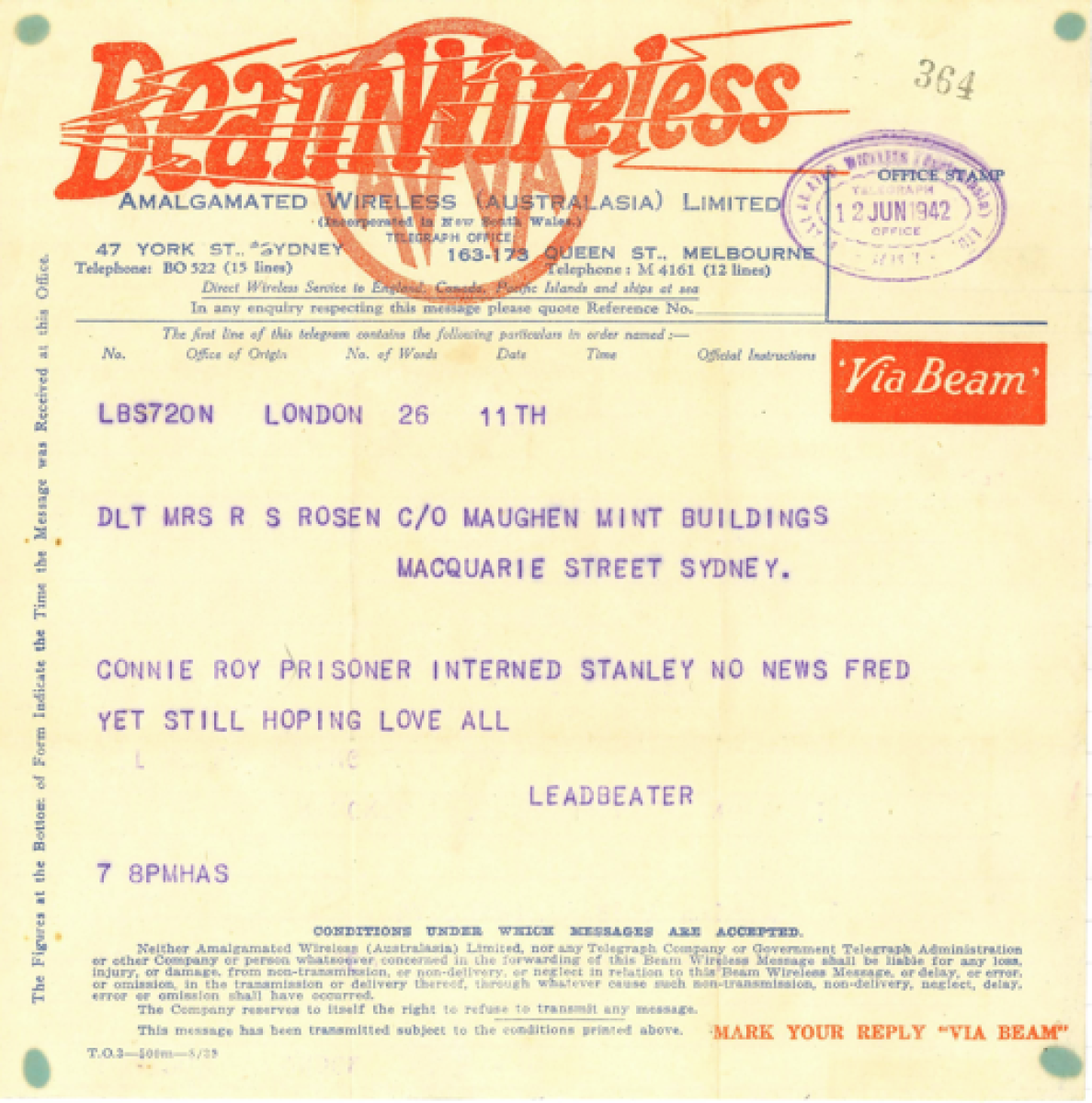

Telegram | 11th June 1942

Telegram | 23rd July 1942

Telegram | 19th October 1942

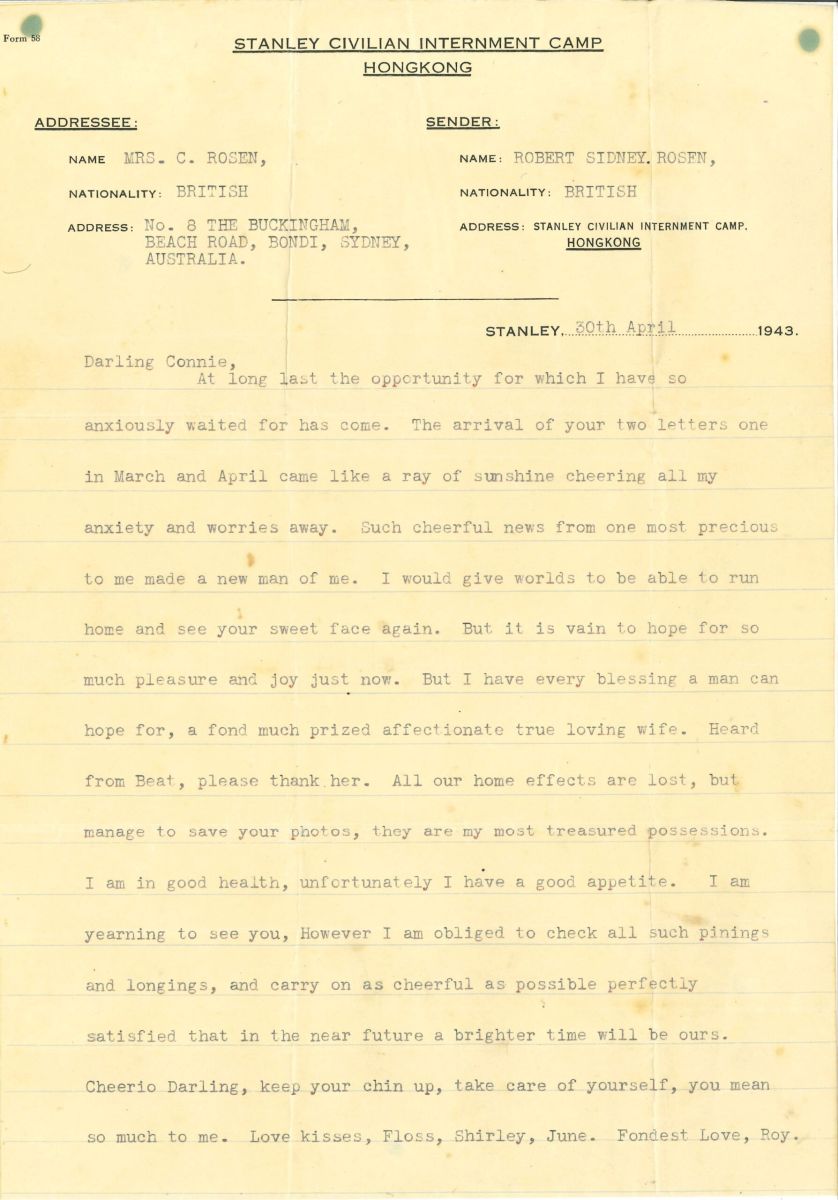

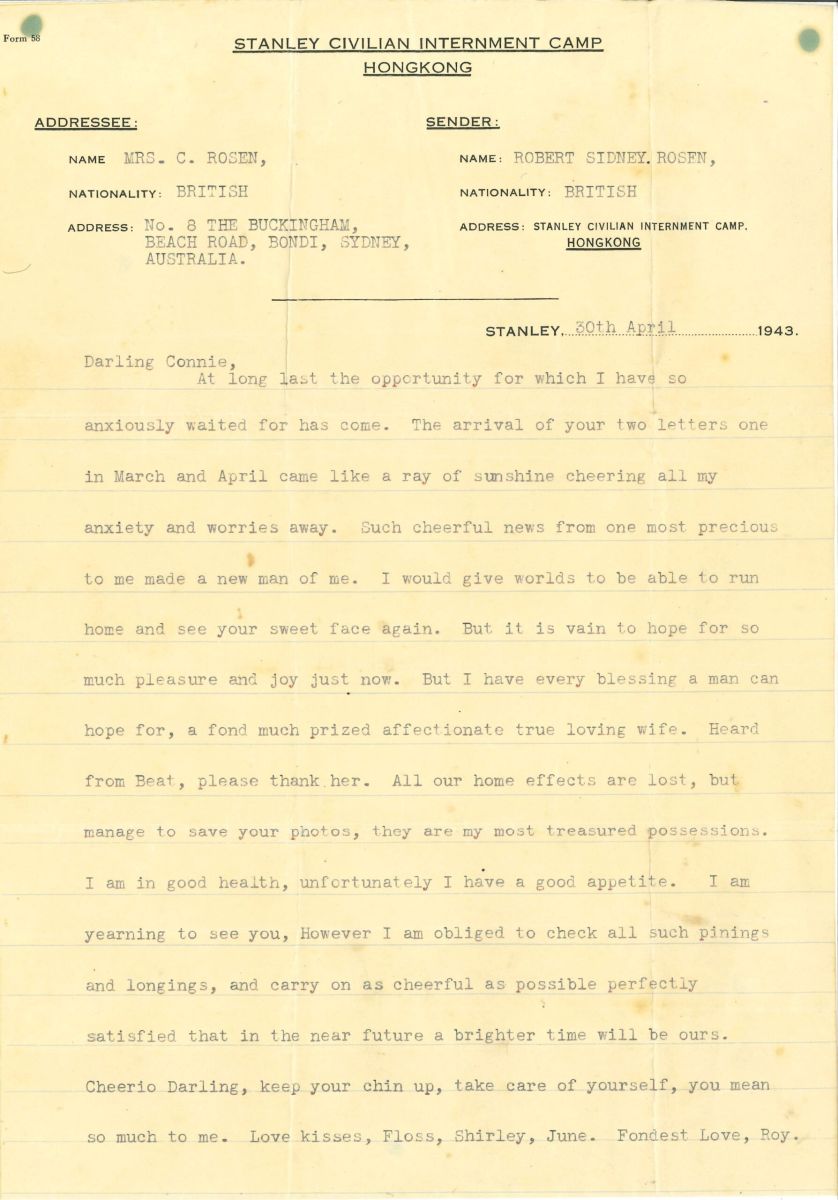

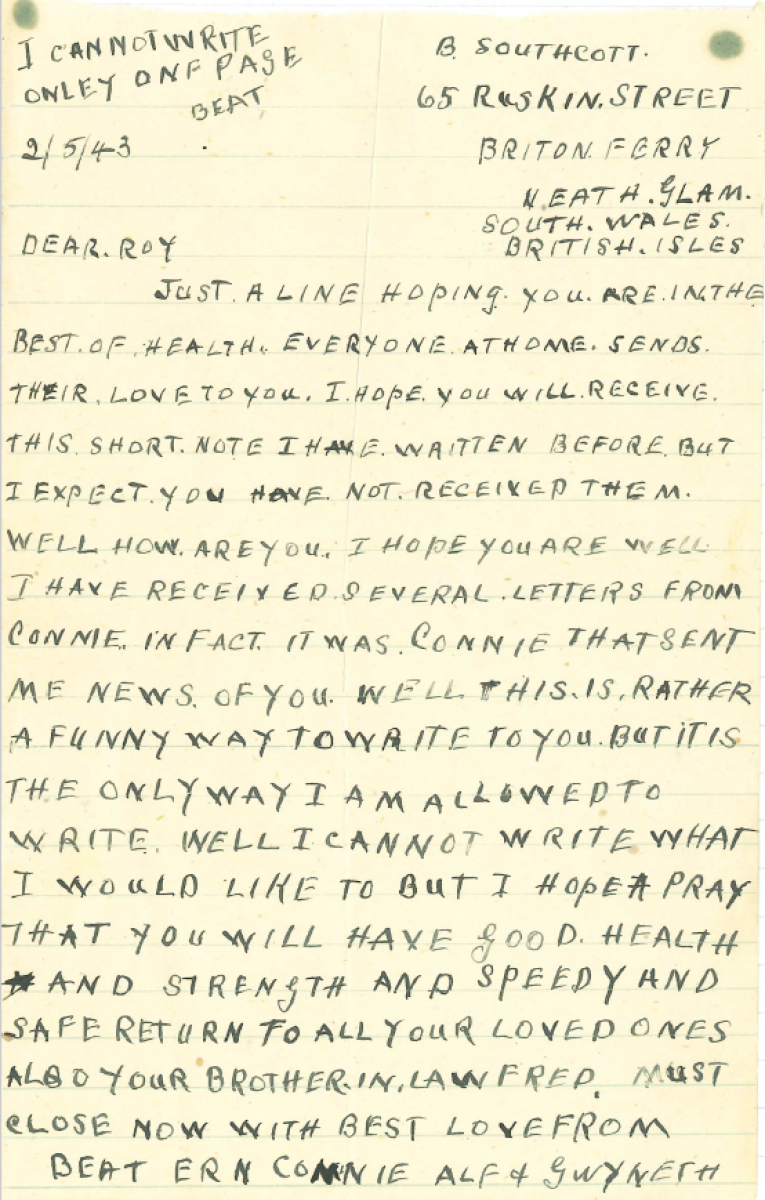

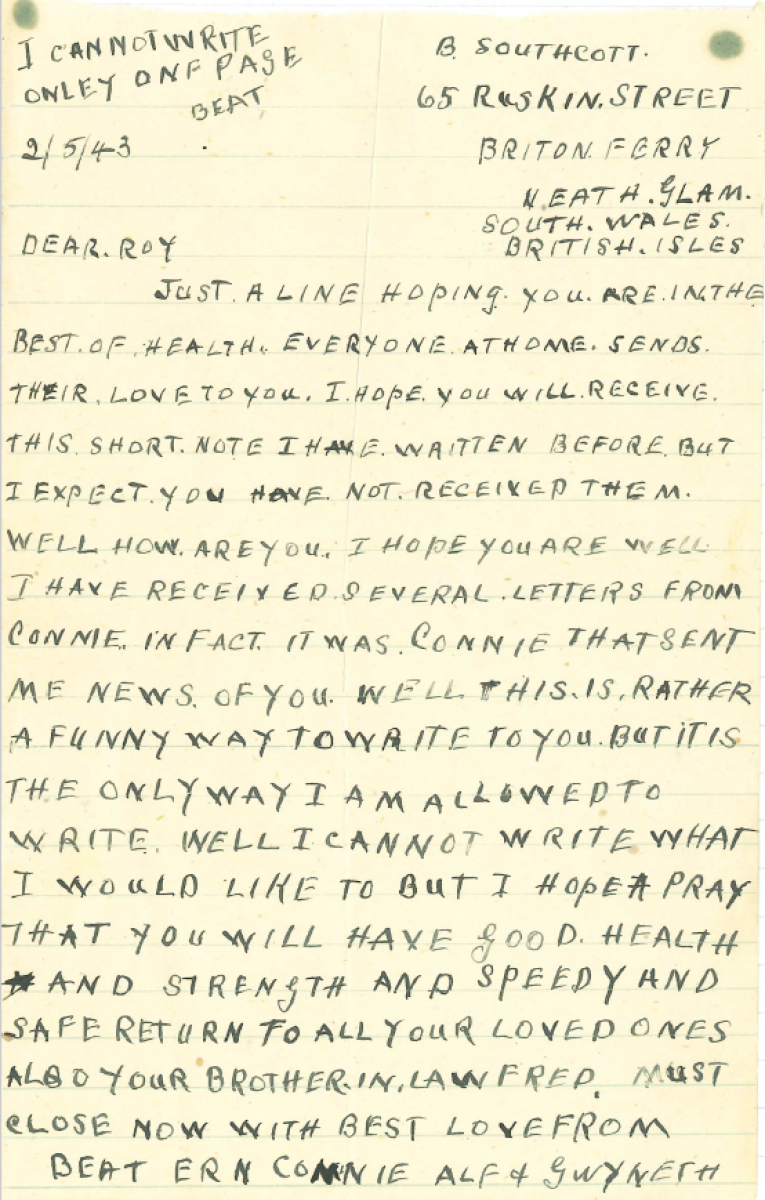

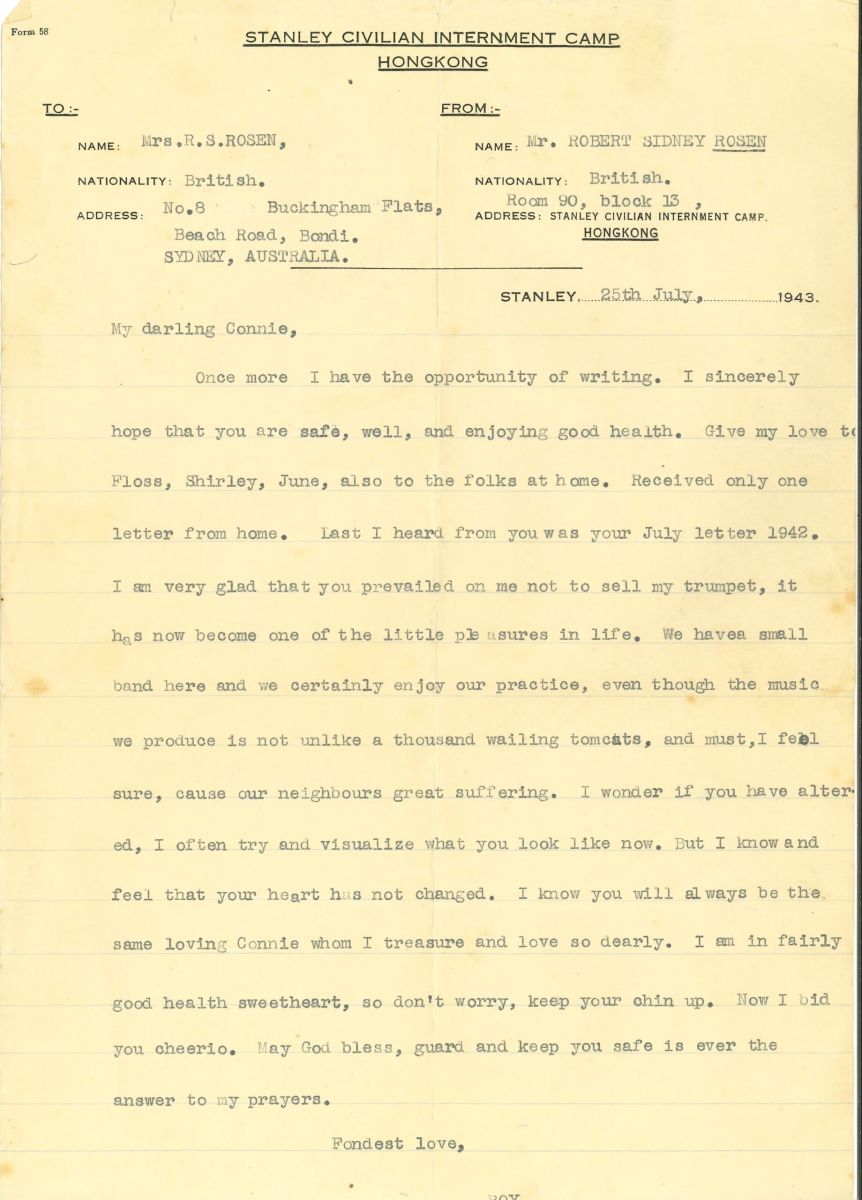

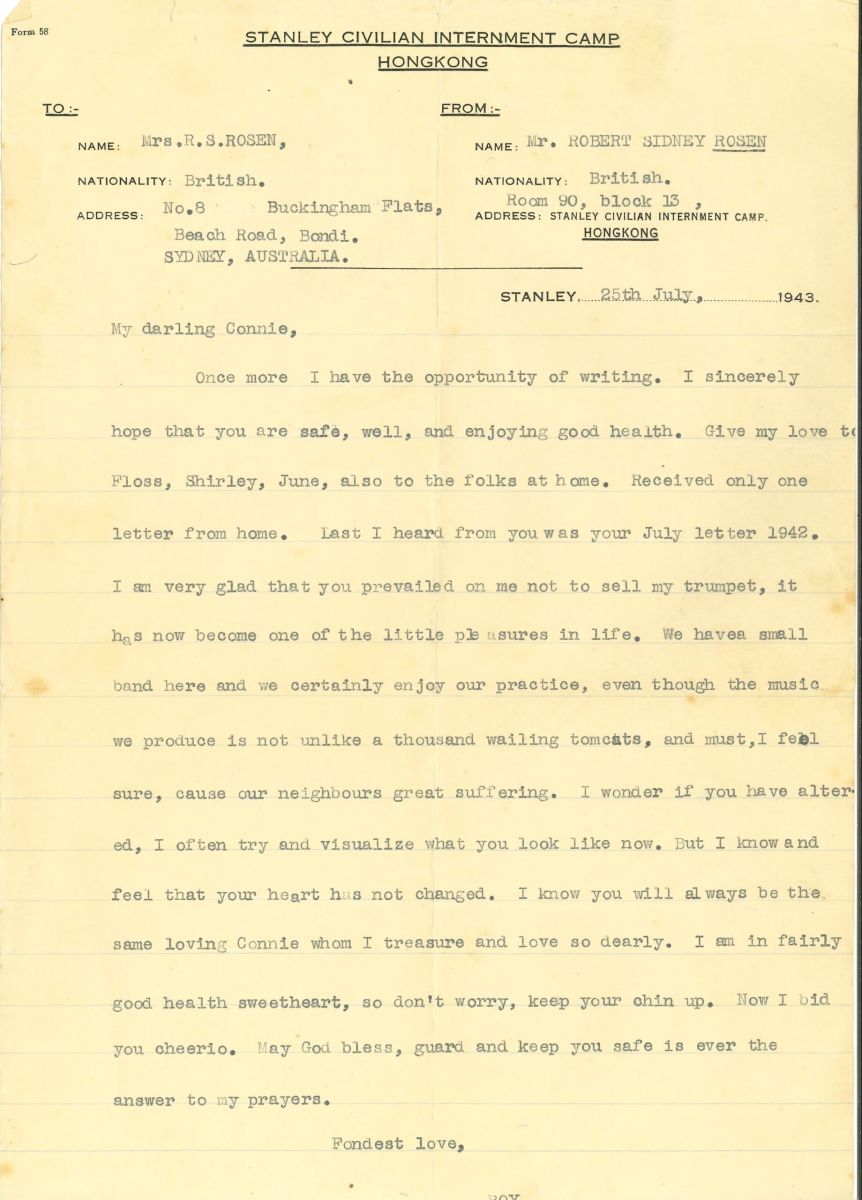

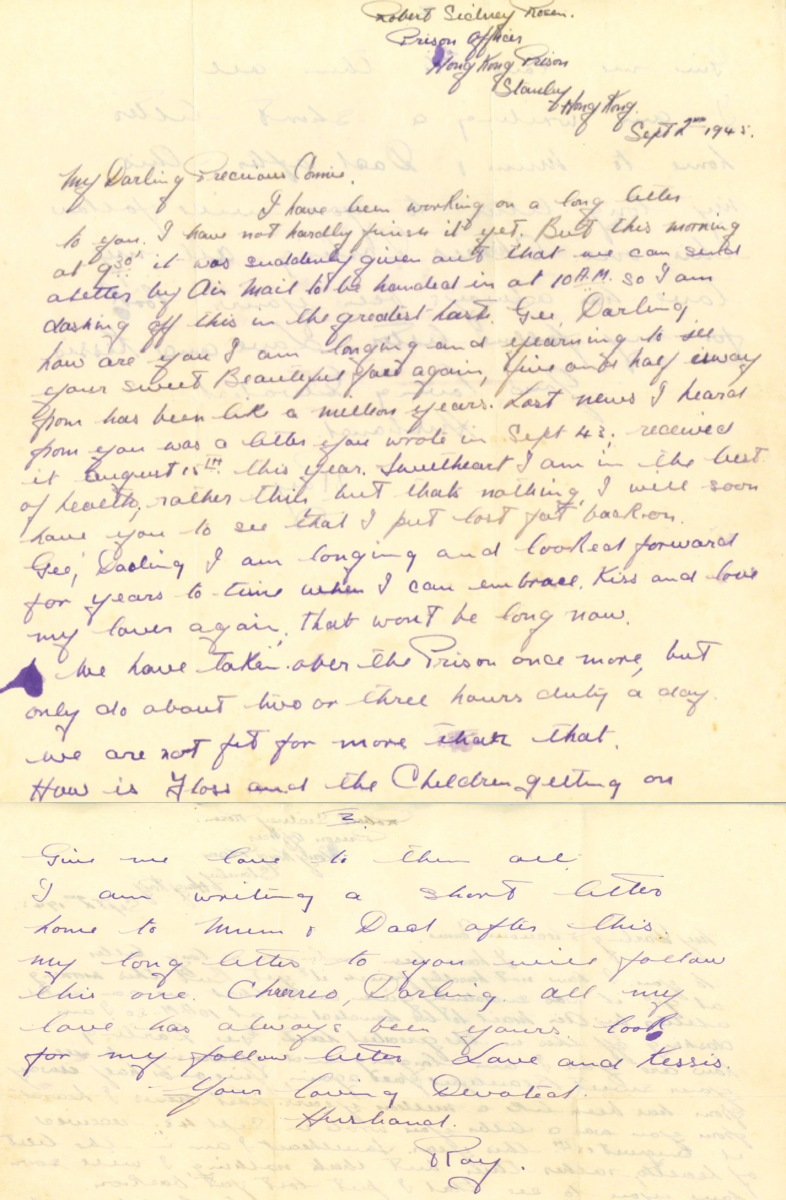

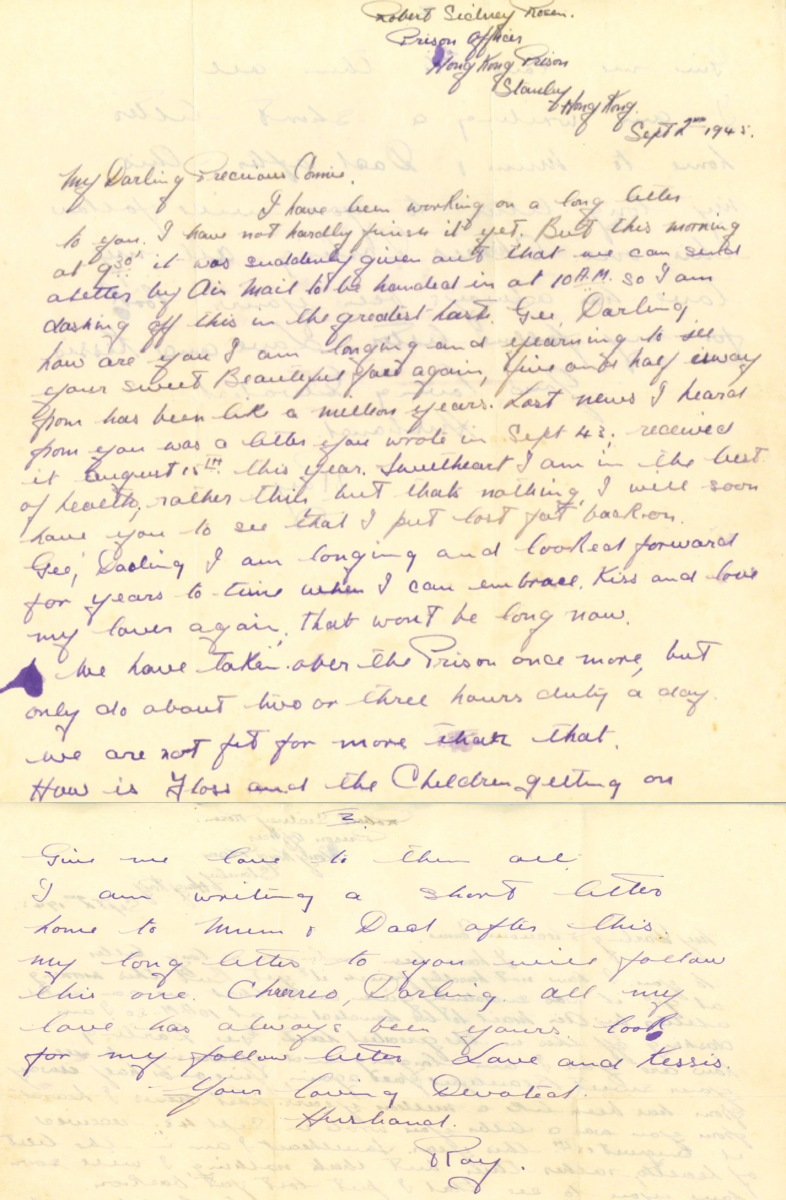

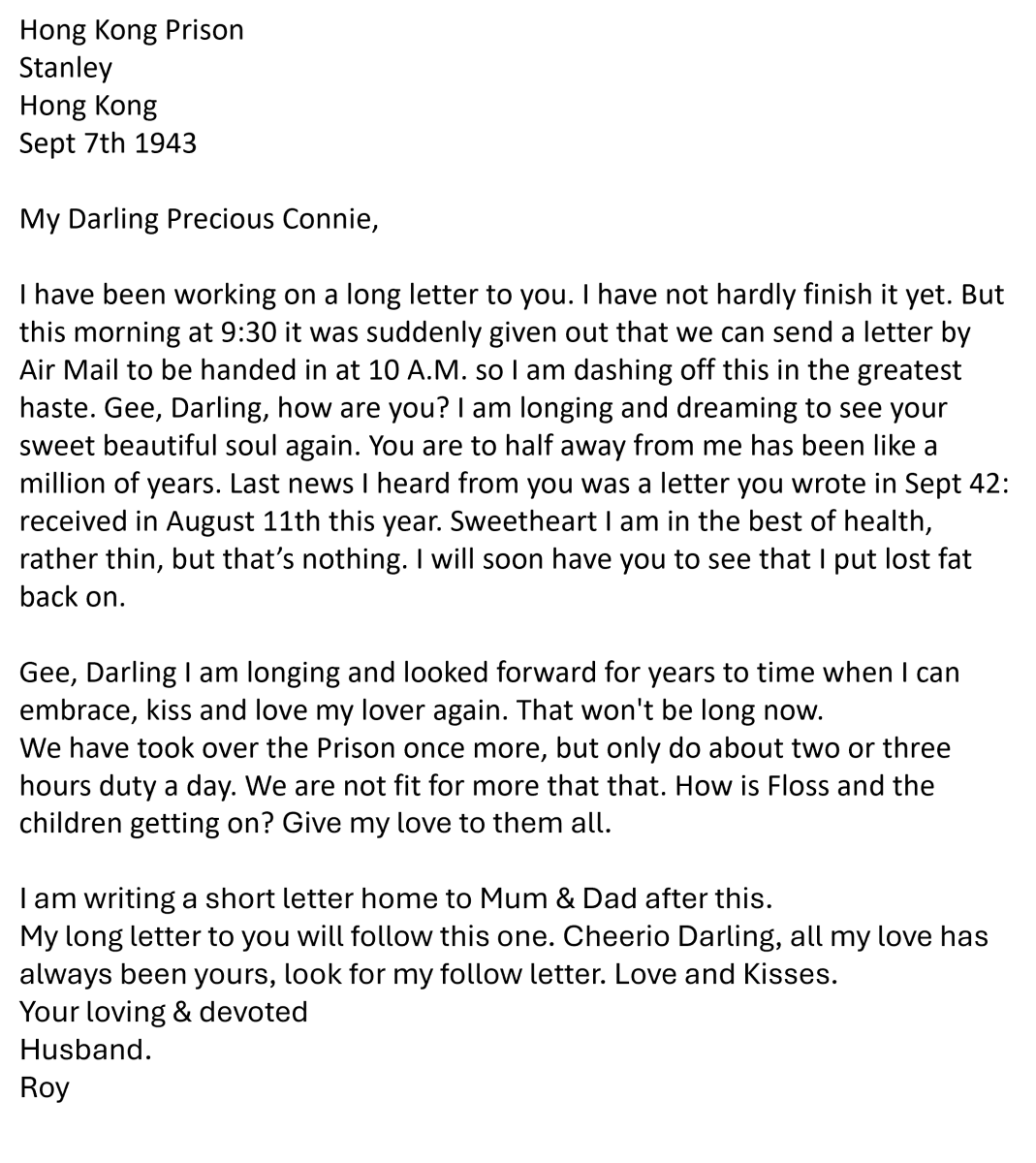

LETTERS FROM POW CAMP | Sent by Roy to his wife. Letters were scruntinised by the Japanese, so POWs had to present a positive view of Camp life.

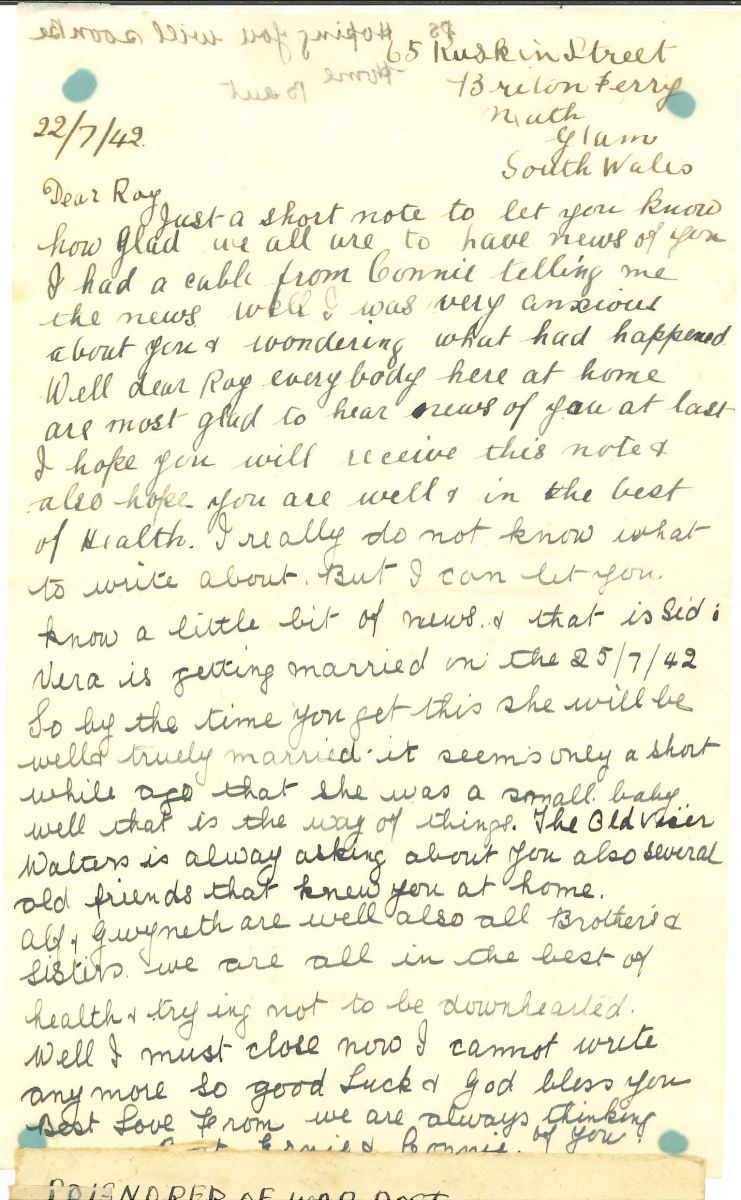

Letter | 22nd July 1942

Transcript | 22.07.1942

Letter | 20th April 1943

Letter | 2nd May 1943

Letter | 25th July 1943

Letter | 2nd September 1943

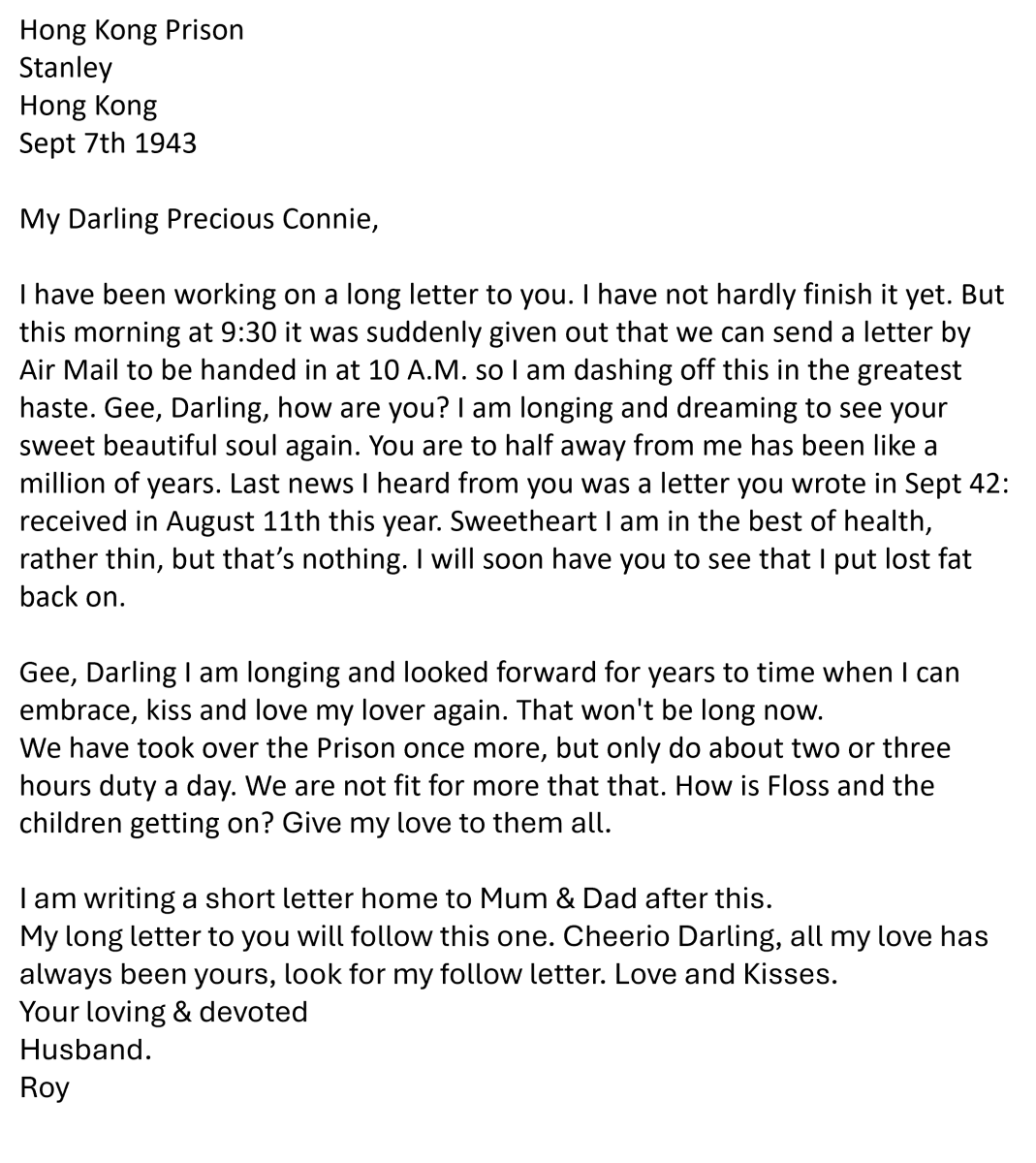

Transcript | 07.09.1943

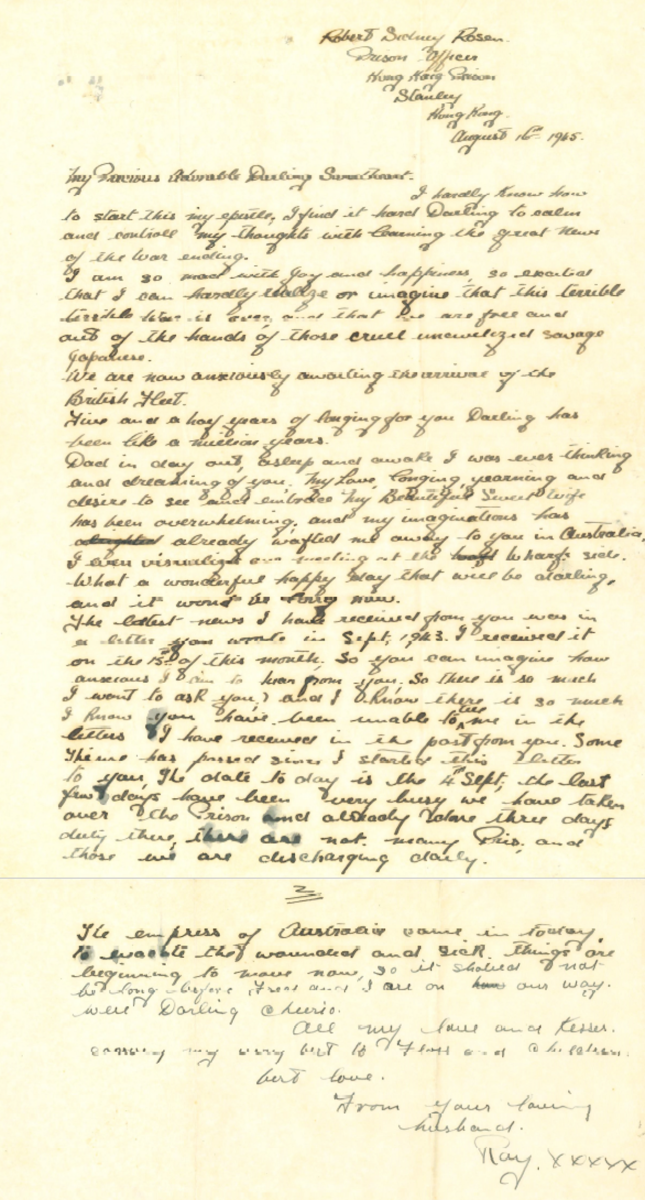

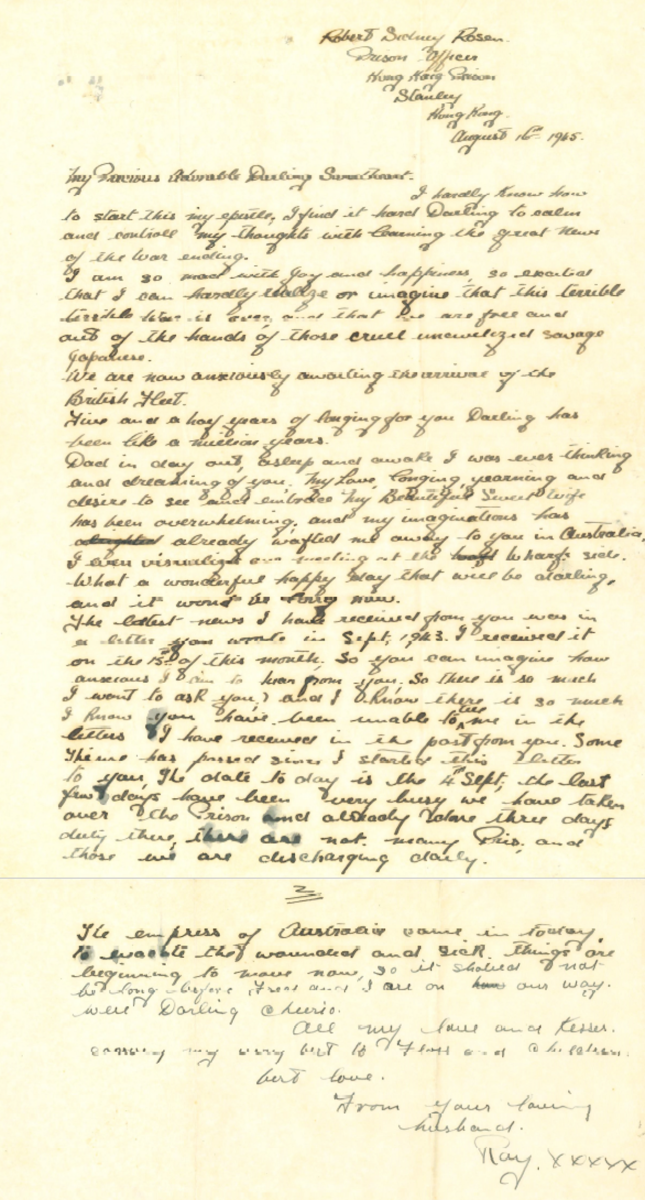

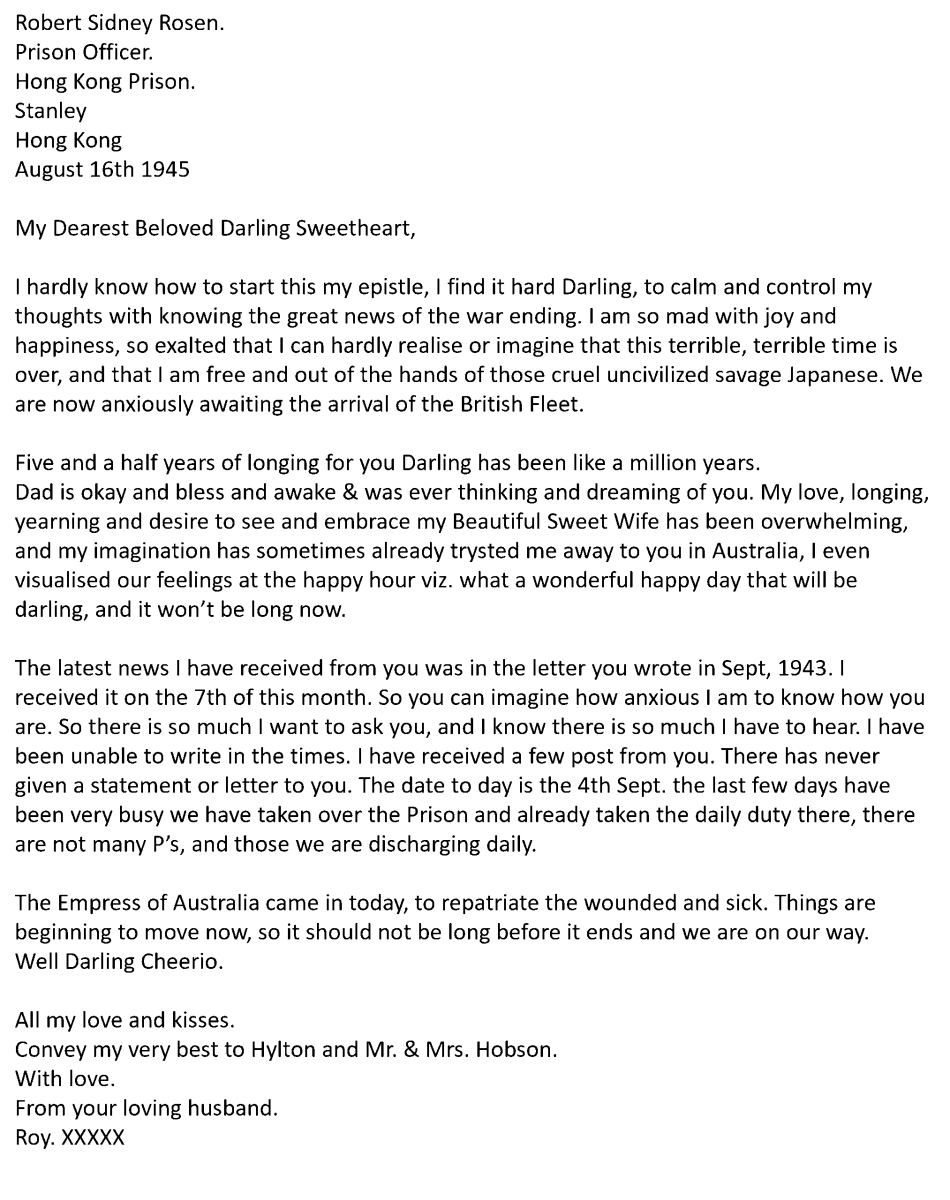

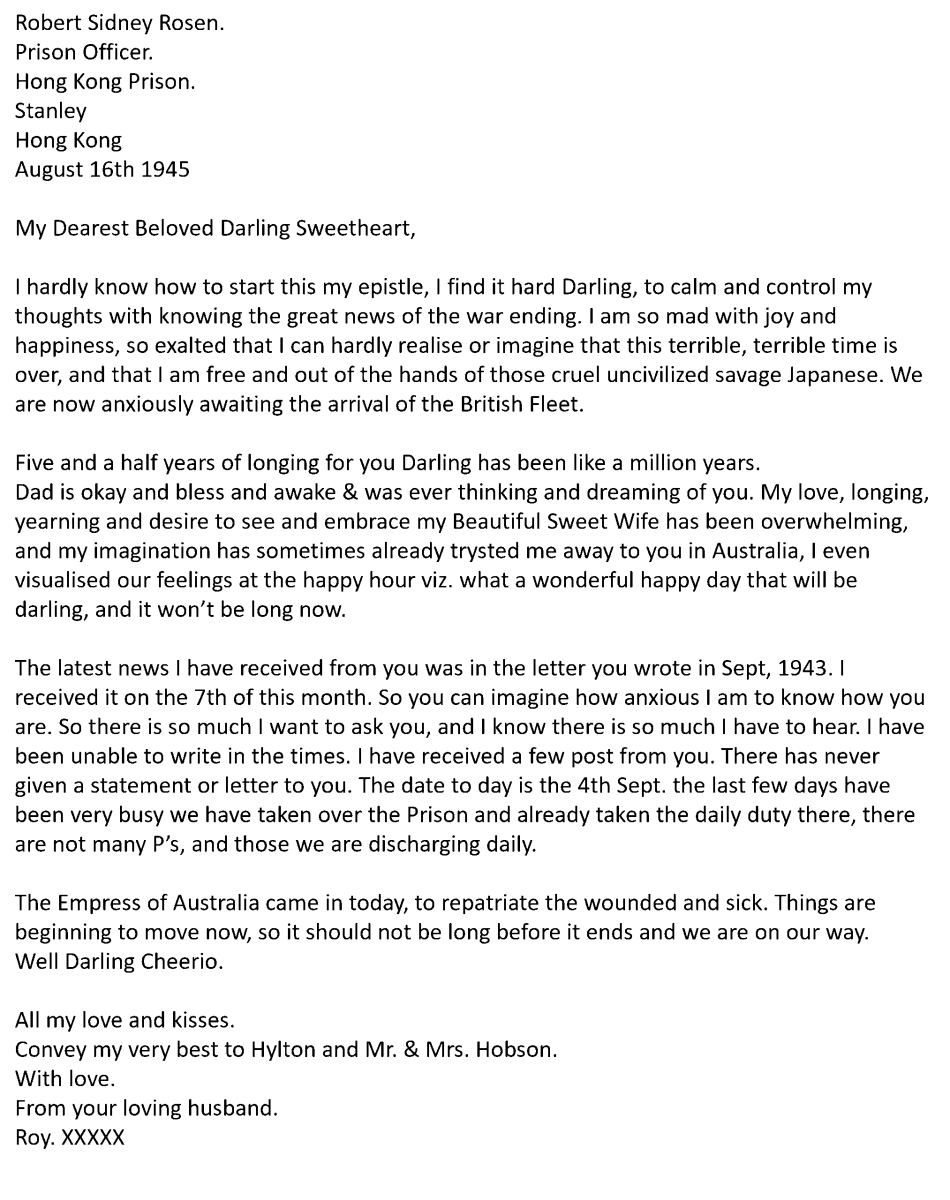

16.08.1945 | One day after VJ Day, Roy writes to his wife.

Letter | 16th August 1945 | One day after VJ Day

Transcript | 16.08.1945

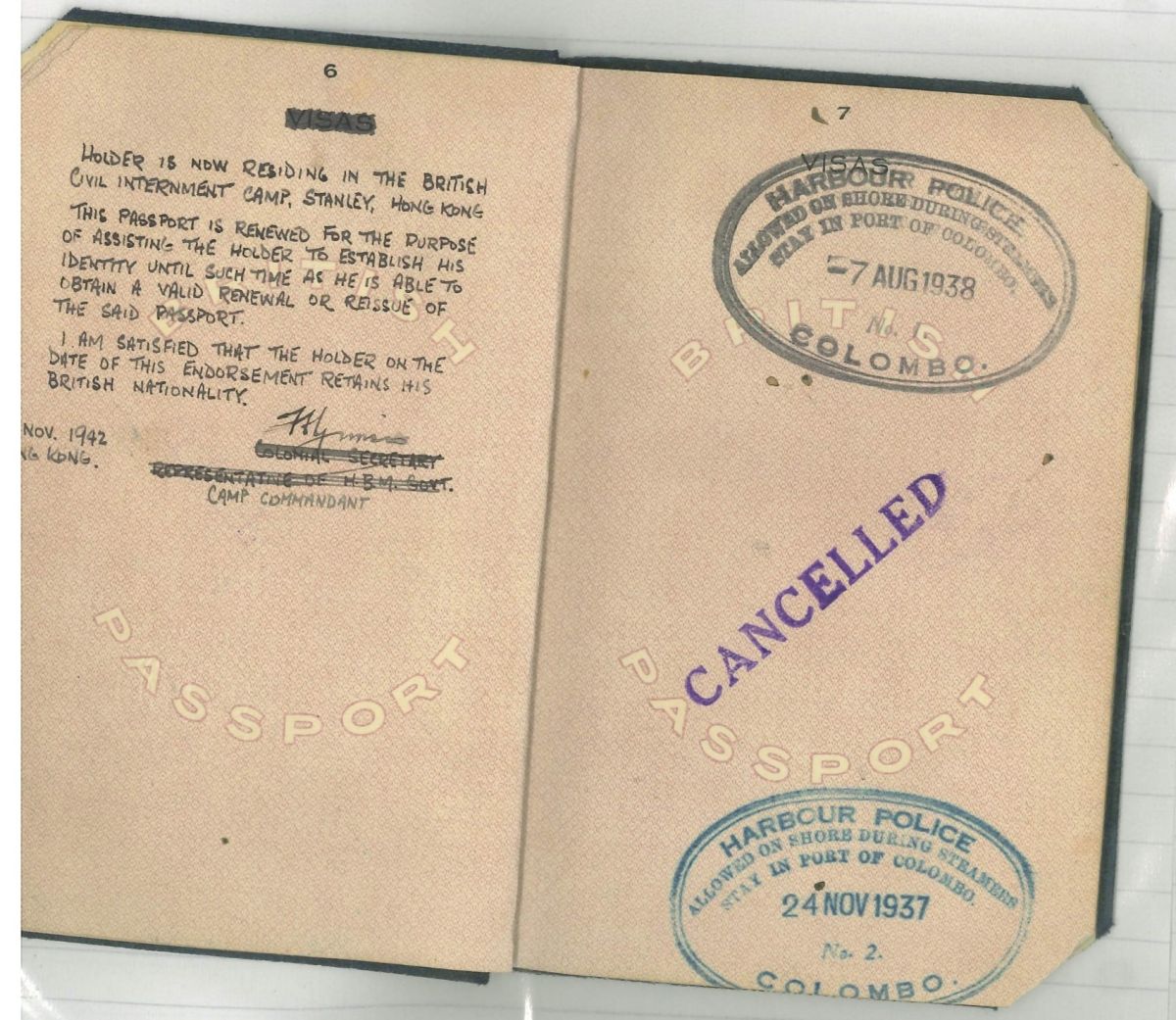

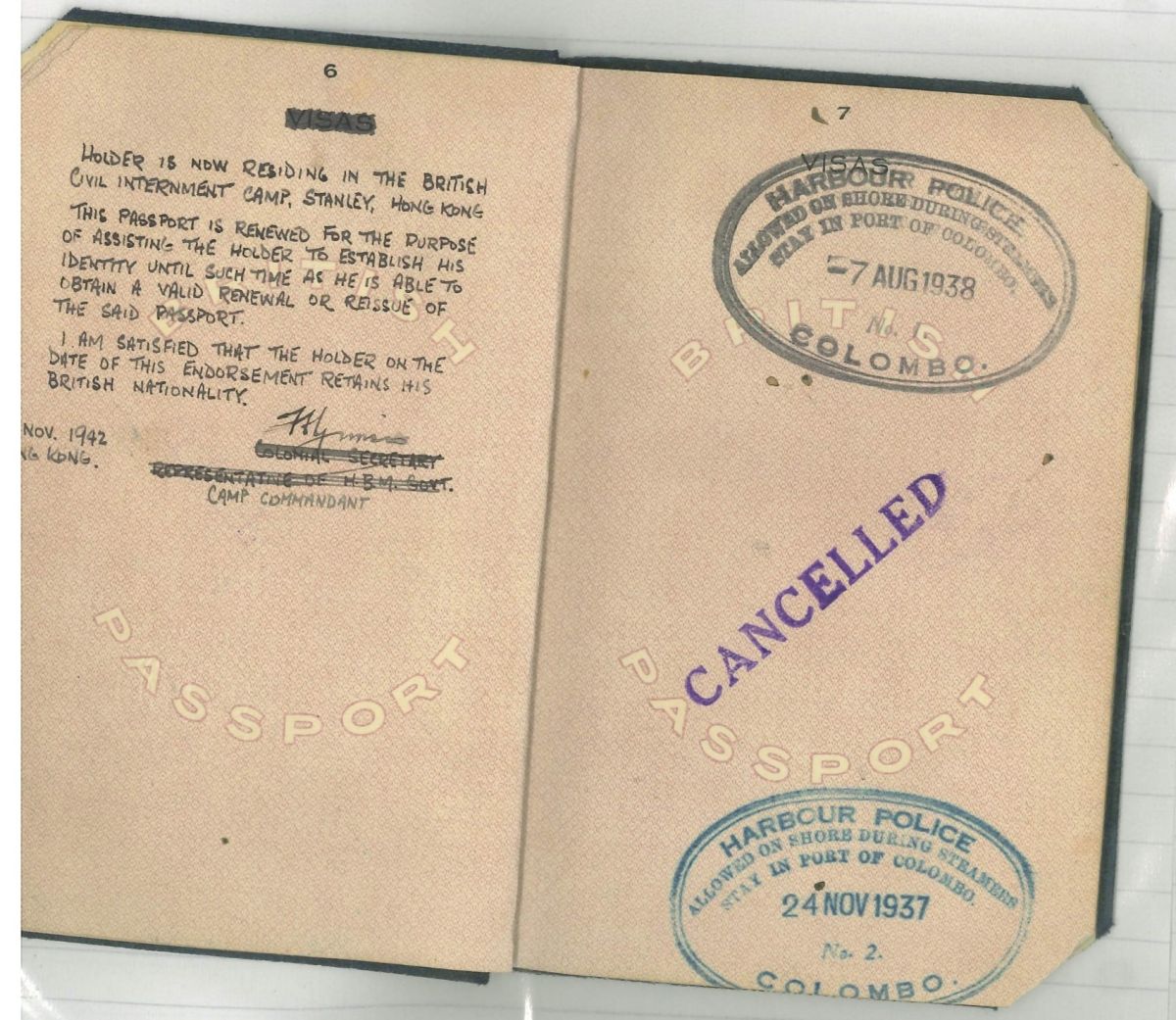

POST-WAR JOURNEYS with PRE-WAR PAPERS

Photo below: Roy left Hong Kong on leave and travelled to Australia, arriving in October 1945 to reunite with Connie for the first time since March 1940. He made the journey using his original passport, which had officially expired in 1943 but had been revalidated while he was in the prison camp.

LIFE IN HONG KONG POST WAR

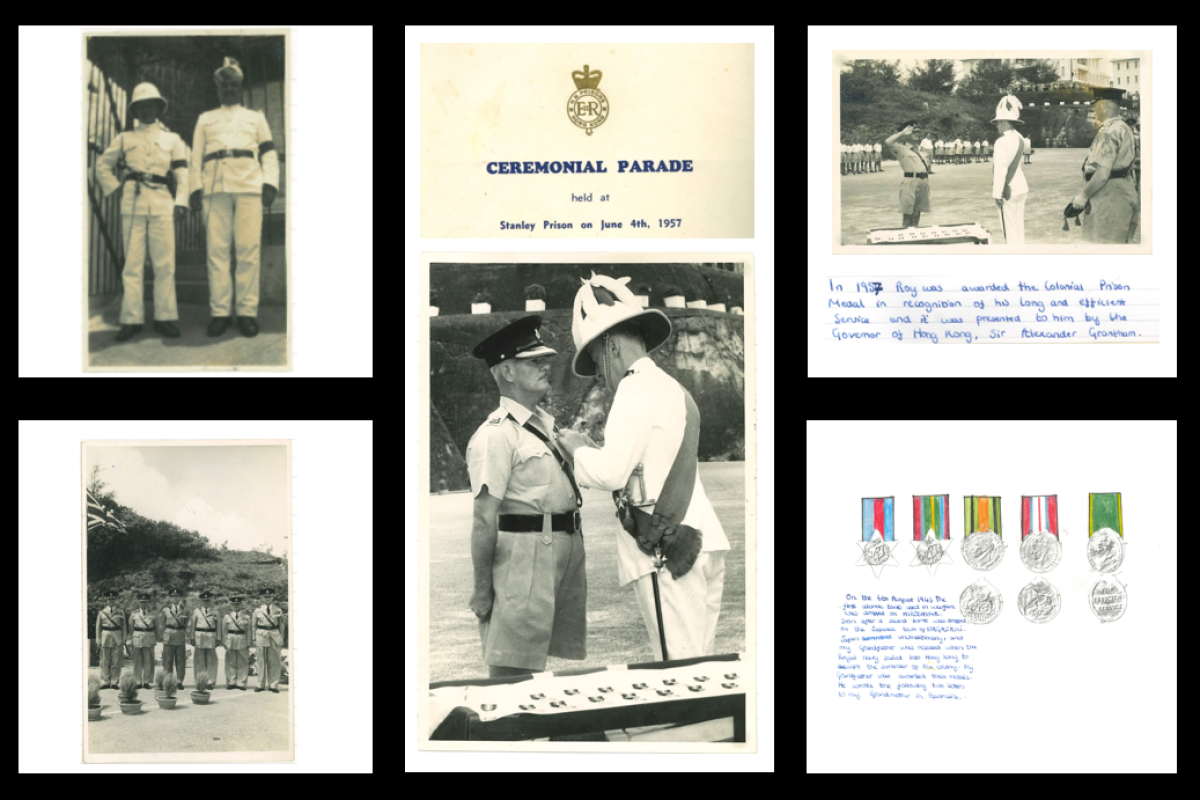

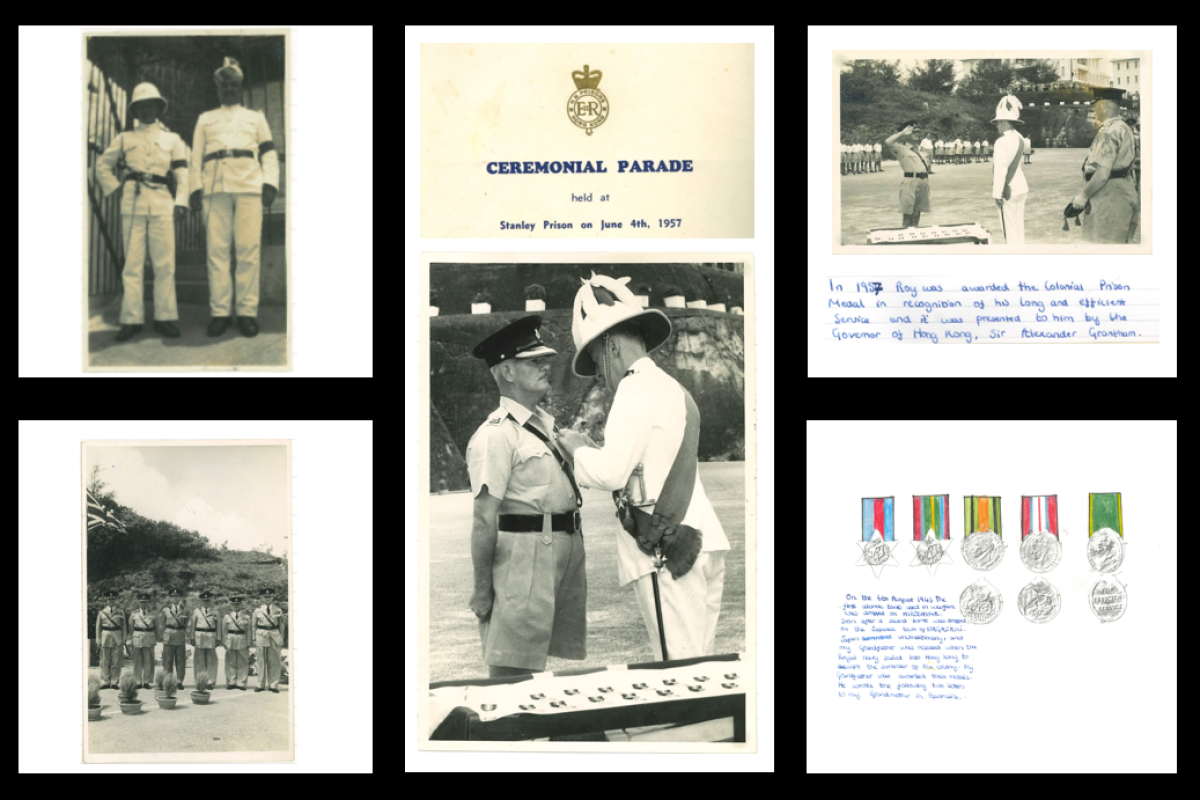

Photos below: After serving in the Army, ‘Roy’ Rosen became a prison warder at Hong Kong Sydney Island Prison. 1957 he was honourd for his service.

ROBERT SIDNEY ROSEN MEDALS

Photo above: The 1939-1945 Star | The Pacific Star | The Defence Medal | The 1939-1945 Medal | The Hong Kong Sufficient Service Medal | The Colonial Prison Service Medal For Long Service and Good Conduct. (The first one ever presented)

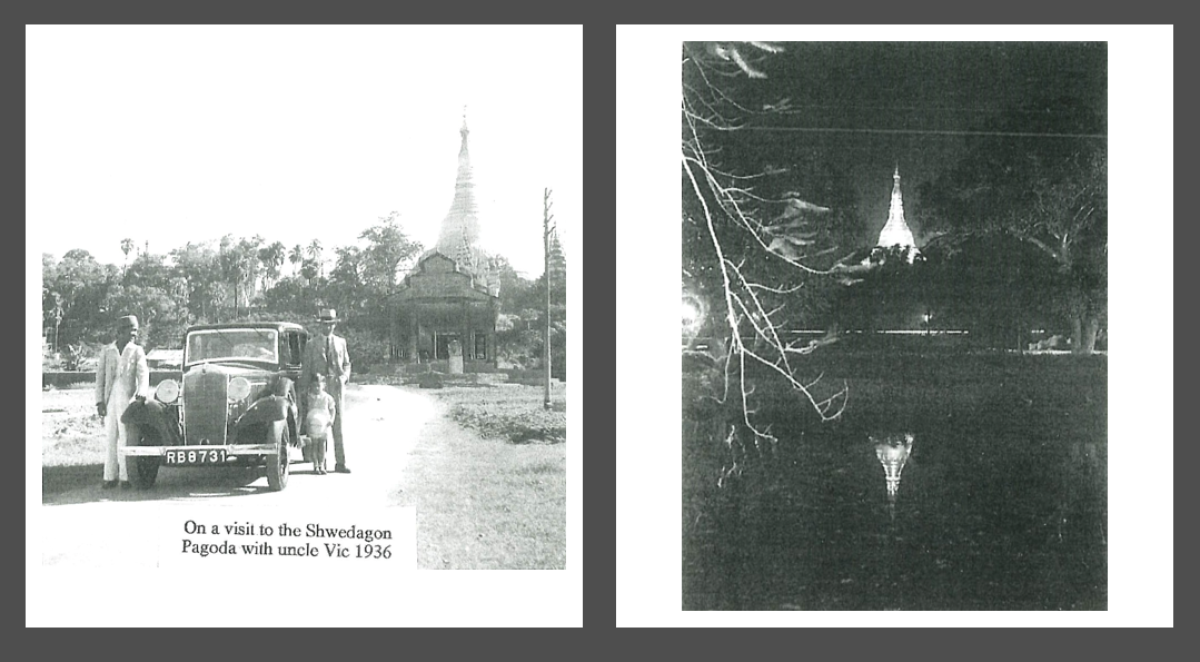

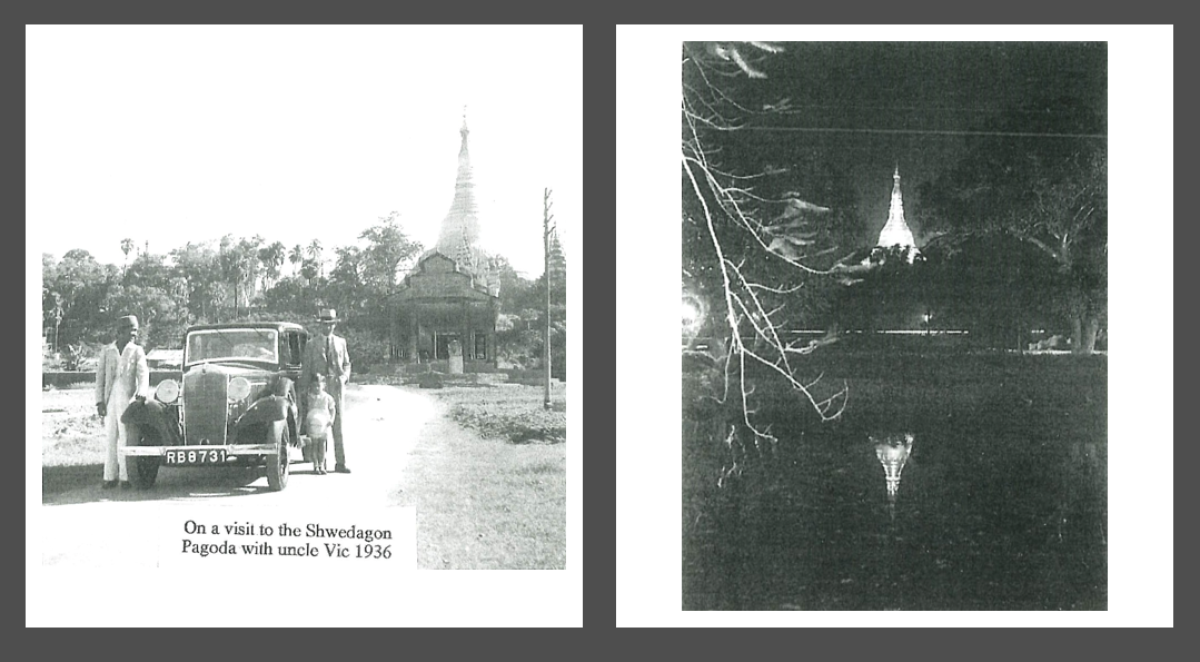

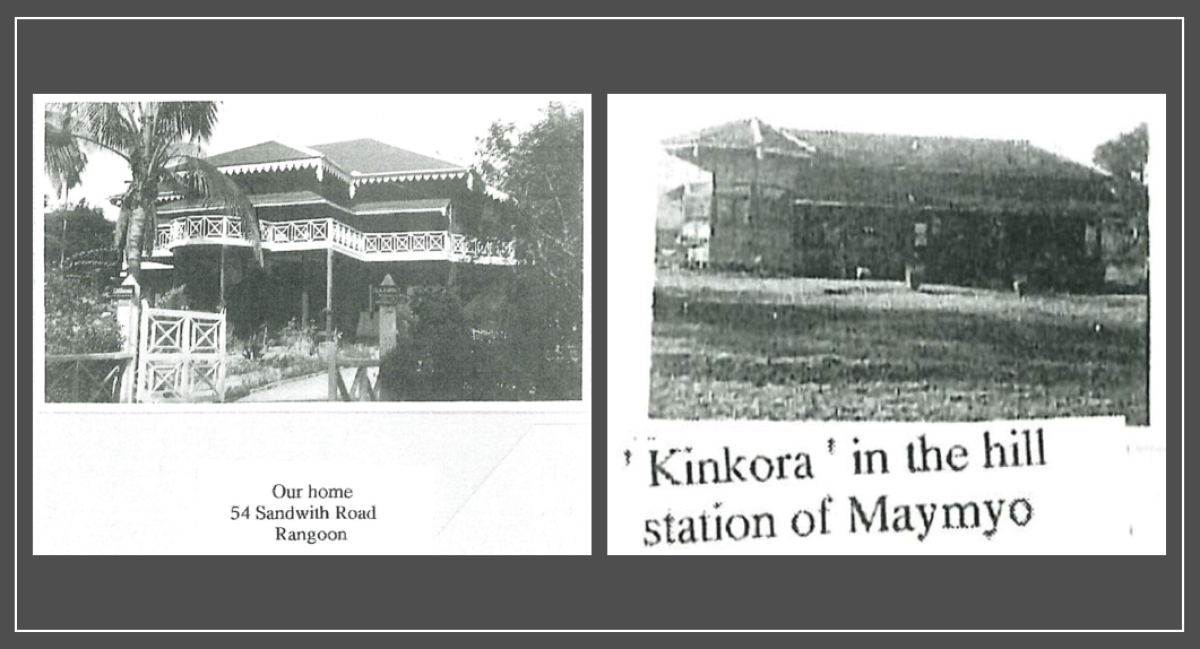

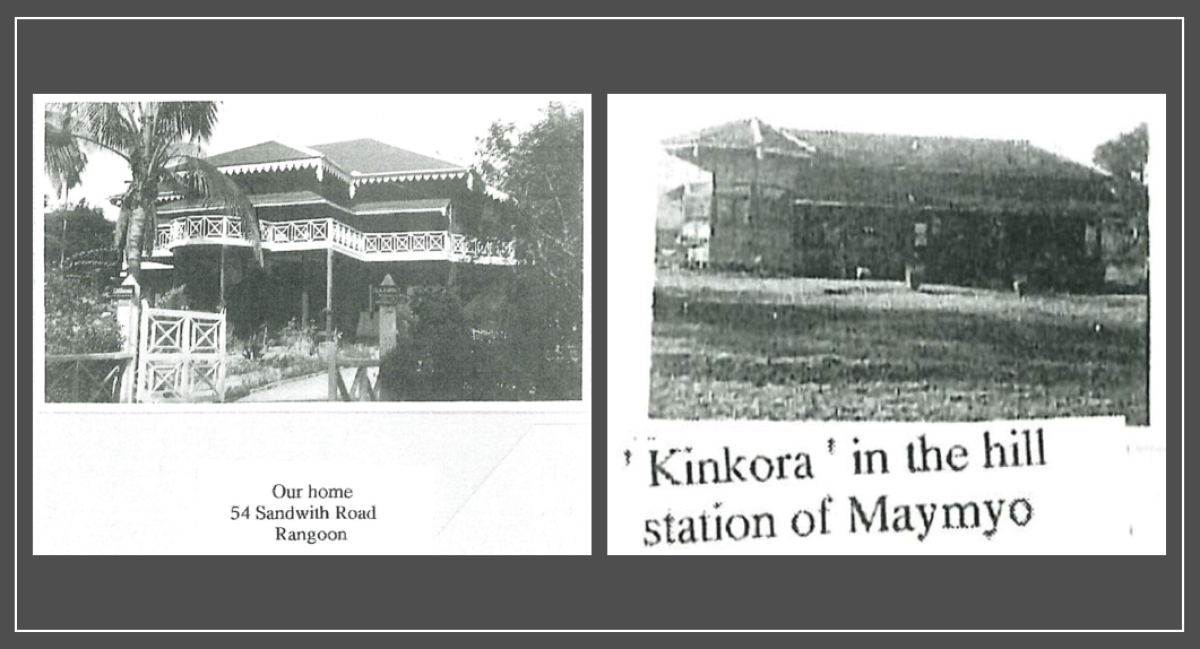

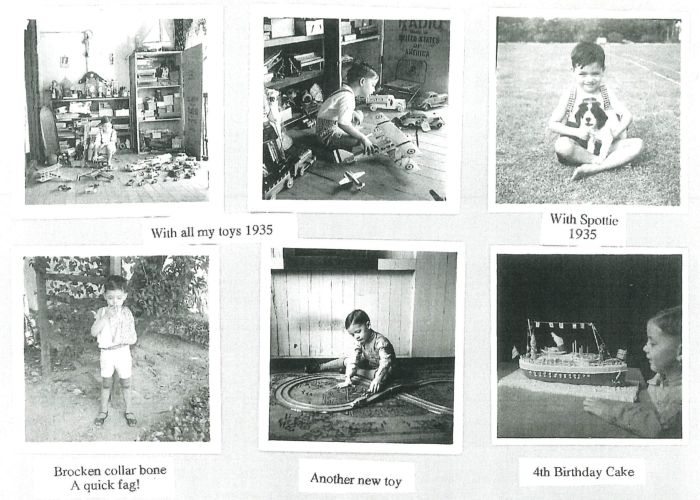

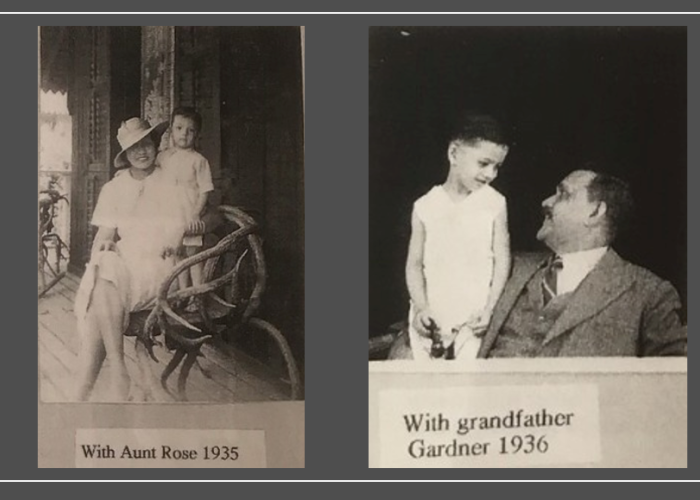

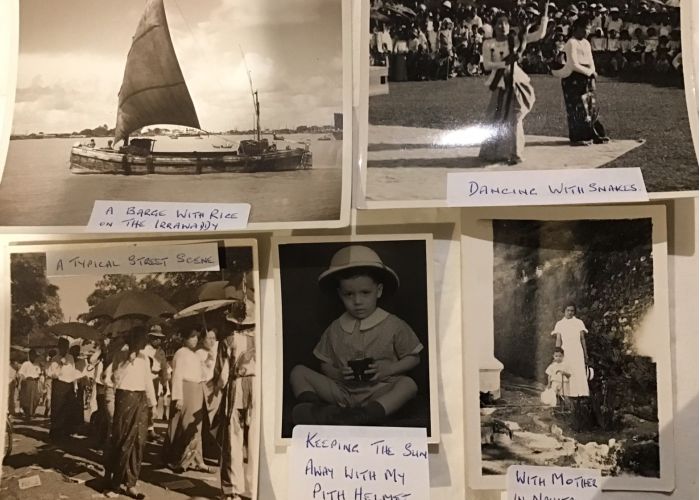

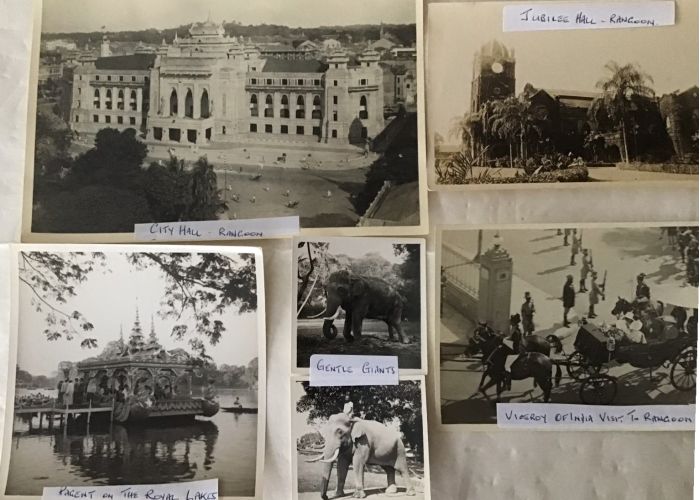

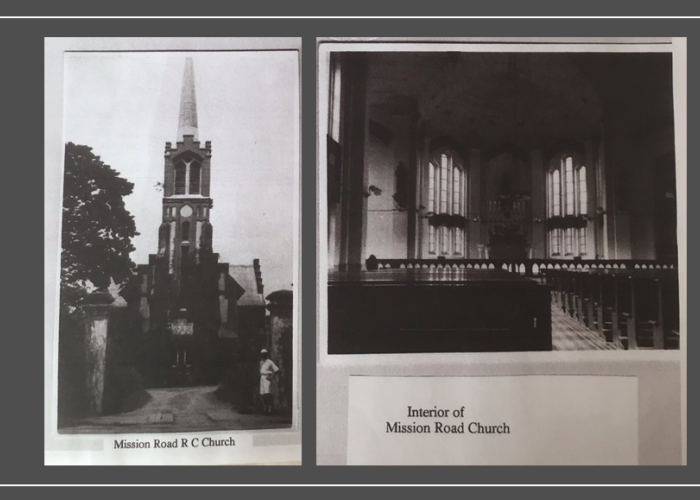

Terence Diekmann, A Childhood in Pre-War|Wartime Burma Remembered

Terence Diekmann shares his personal account of growing up as a child in Rangoon, Burma.

Click here for a full account of his Heritage and Journey

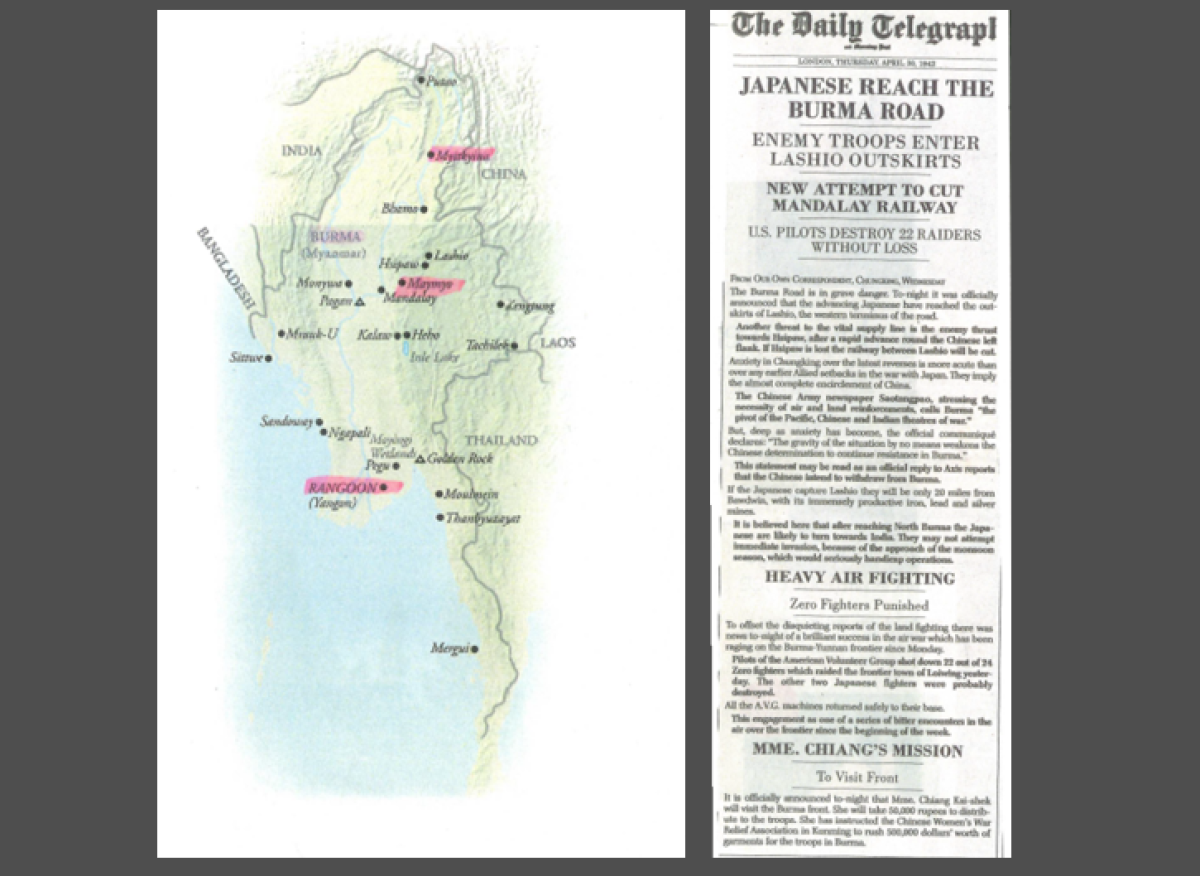

Terence Diekmann began his early life in Rangoon, Burma, Aged 10 years, the outbreak of the Second World War in the Far East dramatically altered his life. Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Rangoon came under heavy Japanese air raids, one of which almost killed his family.

In early 1942, Terence and his family moved to Maymyo, a hill town near Mandalay, to escape the bombings. When Japanese forces advanced further into Burma, they were again displaced, traveling north to the remote town of Myitkyina near the Assam border. Despite his father’s efforts, the family could not secure evacuation by air and found themselves stranded as Japanese forces closed in.

Rangoon House | Maymyo House

-

Childhood in Burma -

Childhood in Burma -

Family Life in Rangoon -

Family Life in Rangoon -

Sights of Rangoon -

Mission Road R C Church -

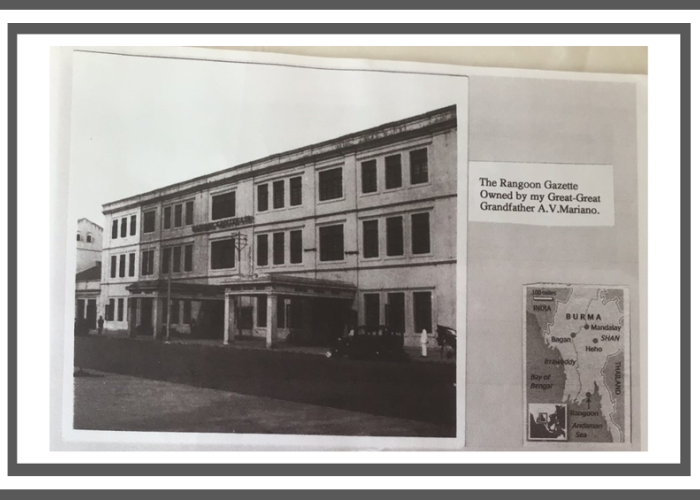

The Rangoon Gazette -

Japanese Propaganda | Local Currency during Occupation -

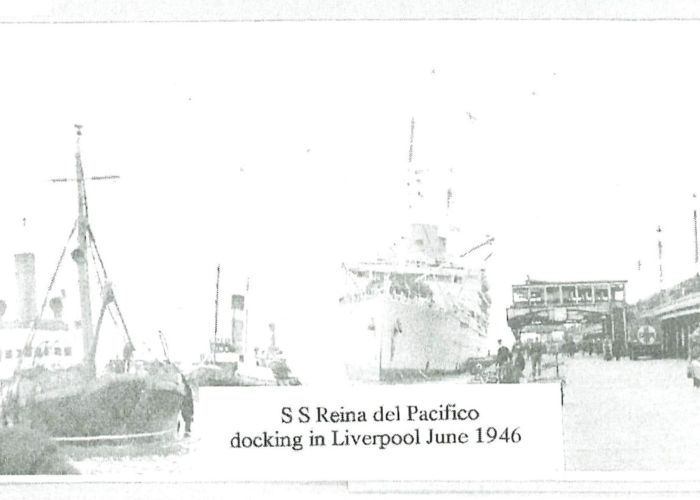

SS Reina del Pacifico | Liverpool June 1946

Faced with no safe escape, they endured life under Japanese occupation in primitive conditions, surviving in bamboo shacks without electricity or running water. The family relied on bartering jewellery for food and used creative means like catching fish in paddy fields to supplement their diet. Eventually, in October 1943, they were interned in a Japanese concentration camp in Maymyo with other British subjects. Life in the camp was harsh and cut off from the outside world.

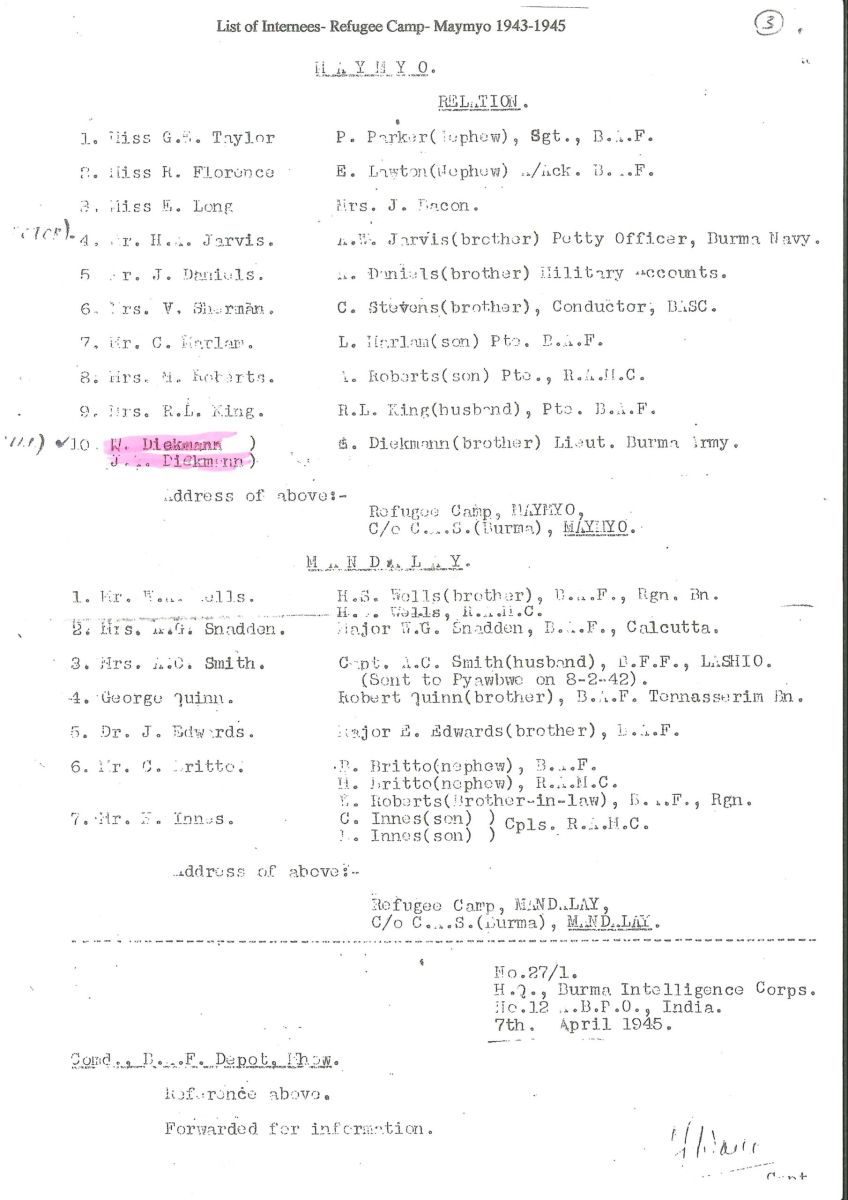

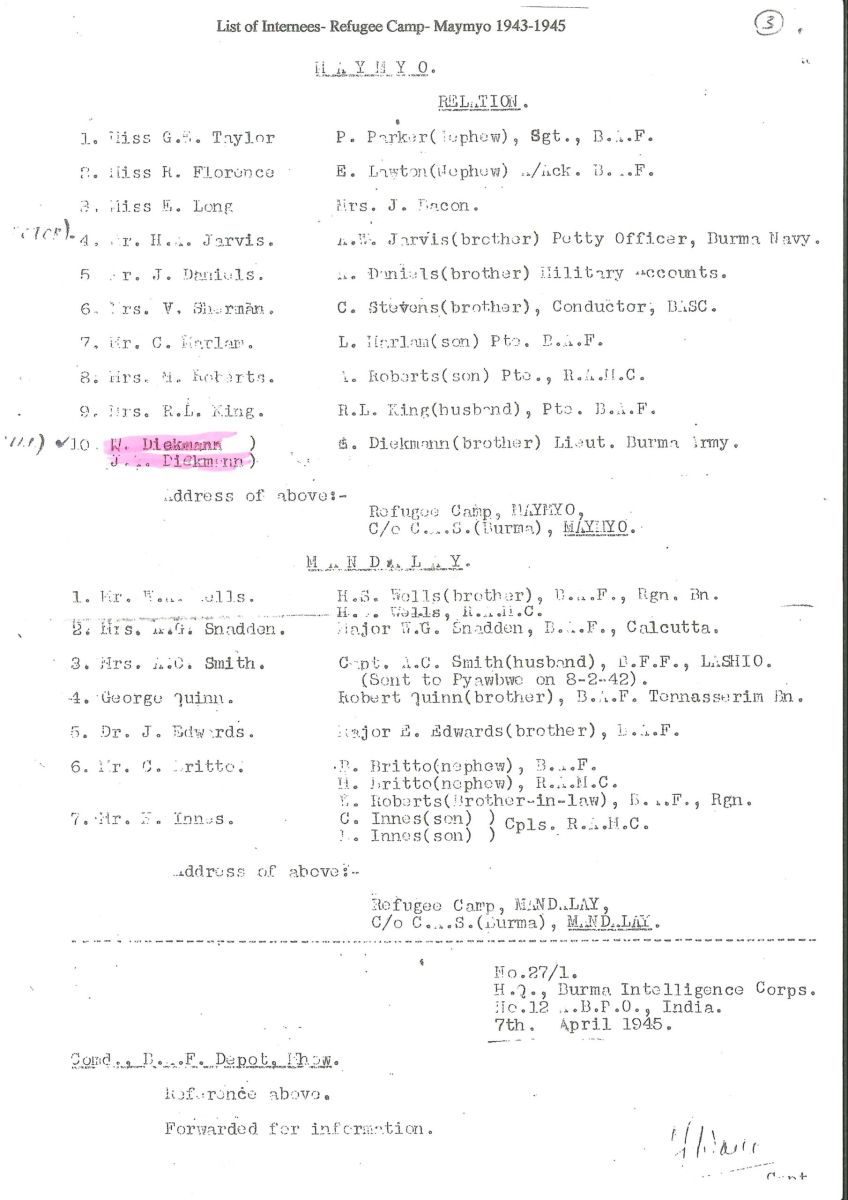

List of Internees – Refugee Camp – Maymyo 1943-1945

In March 1945, the family was liberated after 42 months of captivity. Terence’s father was appointed Chief Executive Officer for Maymyo Municipality to help restore basic services. In 1946, the family returned to Rangoon, only to find their home destroyed. Recognizing the need for Terence to resume his education after four years of disruption, the military authorities allowed him and his grandmother to travel to England aboard a troopship.

Terence was accepted into Salesian College in Farnborough, where he caught up on his education, ultimately becoming Head Boy and earning his School Certificate in 1950. After Burma’s independence in 1948, his parents also relocated to England, settling in Twickenham.

Reflecting on his past, Terence expressed deep gratitude for his family’s resilience and sacrifices. He recalls Burma as a beautiful, vibrant country full of kind people and rich cultural heritage—a place that, though now distant and changed, remains vivid in his memory.

A Childhood scarred by cruelty of the Japanese

Michael P Garnett’s Book Japan’s Final Surrender

Book in the VSC Library | Japan’s Final Surrender by Michael P. Garnett

As a background to its content, the following book review is included as follows:

Michael Garnett was born in Essex UK, served his National Service in the RAF and was posted to the Far East for operational service during the Malayan Emergency of the 1950’s. After moving to Australia, he served for ten years as a reserve officer with No 21 (City of Melbourne) Squadron, RAAF. Currently resident in Romsey in Central Victoria, he has authored three monographs on local militia units, one on Yeomanry regiments and now, on the 80th year since the Victory in the Pacific, Japan’s Final Surrender.

This book is a concise and comprehensive history of Japanese aggression in China and on the Manchurian Peninsula brings the reader to the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbour. The British Navy lost its two battlecruisers as the Japanese swept down the Malay peninsula, and thousands of Allied forces became prisoners of war.

Each chapter is kept short in length, to maintain the reader’s interest as each significant location, key figure and incident is visited. Interspersed with the conditions of surrender and surrenders at different locations are descriptions of the Japanese treatment of those in their captivity and the fate of their leaders after the War Crimes Trials held in Tokyo. Not overlooked is the infamous 1944 Cowra Breakout that saw 231 Japanese internees and four Australian lives lost.

Written in a concise and readable style, the text has been generously supported by an excellent selection of photographs and coloured art works and is complimented by a detailed Table of Contents and Index. A fine monograph to help us remember the events of eight decades ago.

Below are some of the photos from this book. Anyone interested in the events which took place throughout the South West Pacific during the 1940’s, may like to refer to the copy which is available in the VSC Library.

In Australia, the book is marketed by the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, through their bookshop.

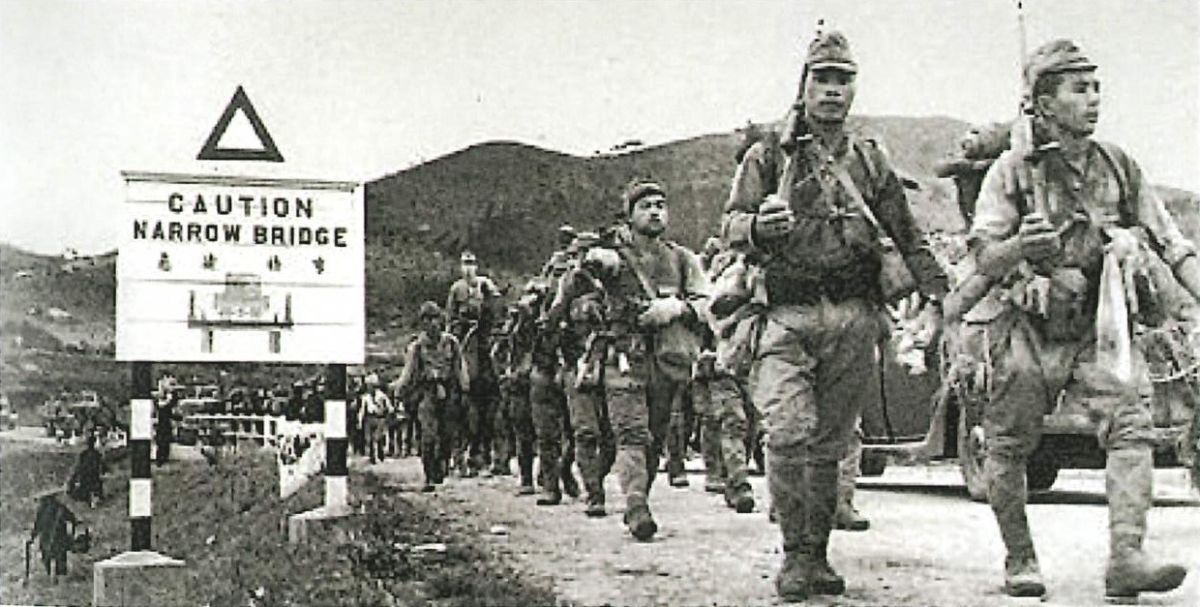

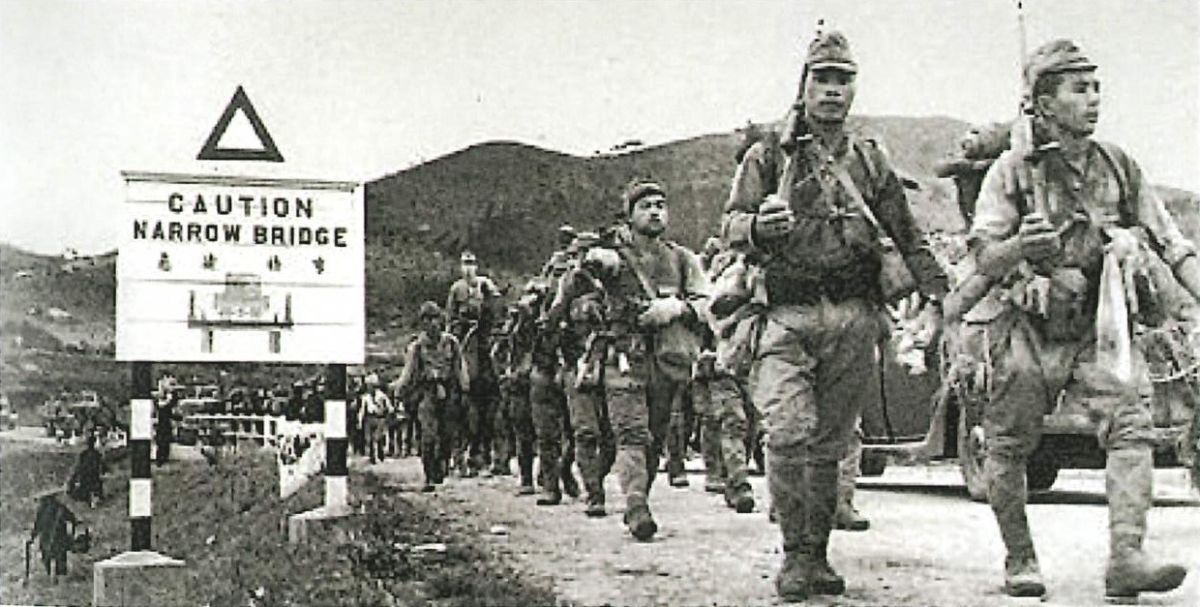

Japanese army – on the march to Singapore…

POWs working on the Burma-Thailand railway

Bombing of Singapore commences

5th September 1945 – 2,600 Japanese prisoners of war line up in a stockade on Guam, Mariana Islands

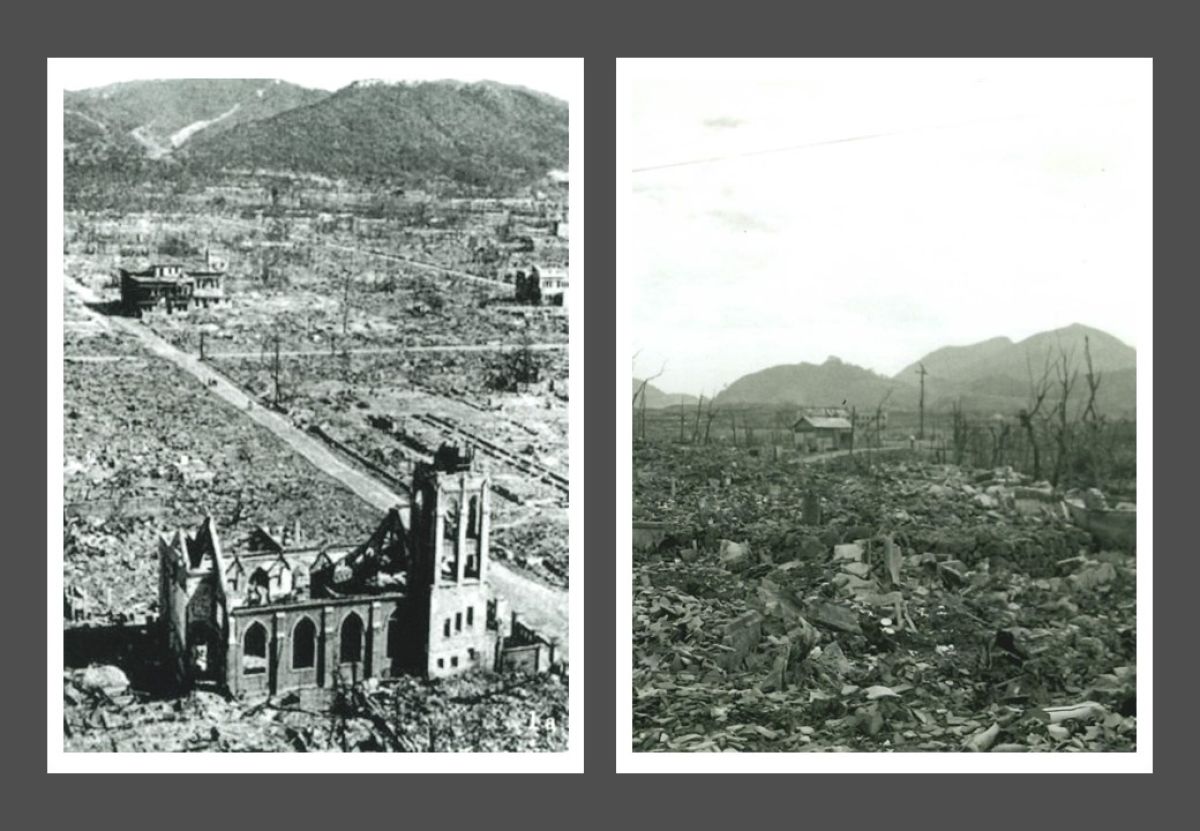

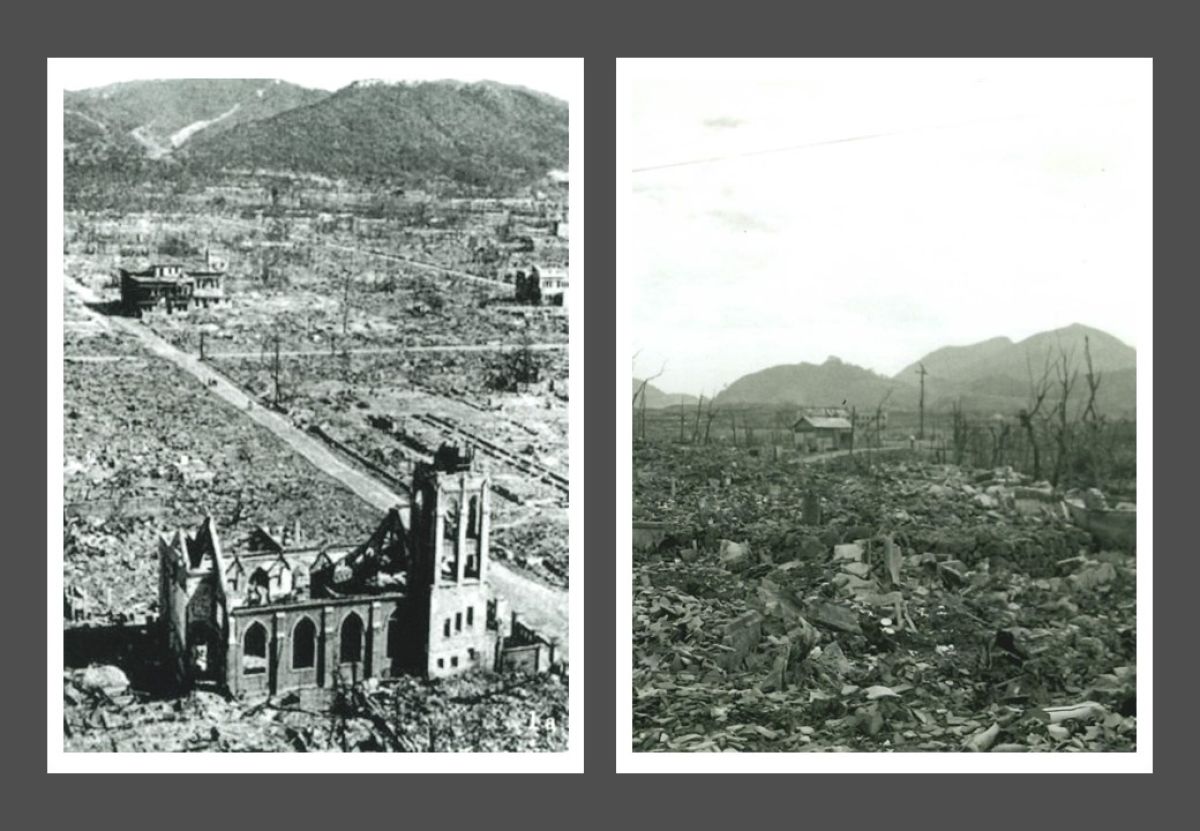

Hiroshima – utter devastation | Nagasaki – the aftermath

The formal ceremony of surrender was conducted by American General Douglas MacArthur on USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay – 2nd September 1945

A line-up of captured ‘Betty’ aircraft

An assortment of Japanese aircraft shipped to USA for assessment before disposal

VSC Members’ Family Stories

Family Recollection—no names—submitted by Lynne Rust

This story, passed down in our family, reflects the emotional toll the war took not just on those who served, but on those left behind—waiting, hoping, and fearing the worst.

My grandparents’ neighbours’ son was a POW under the Japanese. There was no news for a very long time, and they were deeply worried about their only son. Eventually, months after the war had ended, news arrived: he was alive and would be sent to Canada to recuperate.

To celebrate, my nan was invited around mid-afternoon for a sherry. When my grandfather came home from work, he asked my uncle—still a schoolboy at the time—where his mam was.

The reply: “She’s in bed—drunk!”

The worry, the not knowing, the relief—it overwhelmed everyone. A moment so out of character for all involved that it became a much-retold family story, a small but powerful reminder of just how deeply war touched even those far from the front lines.

A VJ Present—submitted by Bob Mitchell

My father was in the merchant navy and my mother was a nurse. He was away at sea in the Indian Ocean when VE day was celebrated, but managed to get back to Liverpool for the VJ celebrations.

The story goes that he left his ship which he had been on for many months with a bottle of whisky and a bottle of sherry. He drank the whisky; my mother sampled the sherry. The pangs of separation tempered by the libations got the better and my mother surrendered much faster than the Japanese. Nine months later I was the result of this celebration, but I remember as a child if I was naughty my mother always blamed the Japanese, never the sherry!

The far-reaching consequences of war—submitted by Ron Hall

My Cousin was captured in Singapore and put to work on the Burma Railway. He survived the war but came home with Tropical Ulcers which proved difficult to heal and he had to go up to London to visit the Hospital for Tropical Diseases to have them treated on a regular basis. He became depressed, could not hold down a job and in the end he took his own life. Another victim of the Japanese.

We should be thankful that the Americans dropped the two bombs which brought the war to an end and probably saved an untold number of lives. Ron Hall